Mapping Student Debt in Western New York

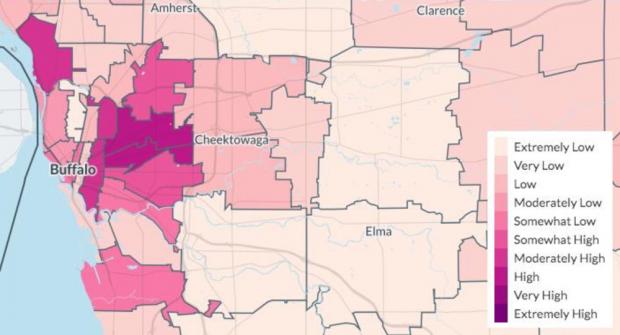

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth recently released Mapping Student Debt, an intuitive visual method for connecting student debt with larger issues of economic inequality. It’s a nifty tool that lets us see how the student debt problems we already knew existed have gotten even worse in Buffalo.

Long story short: Less affluent areas get hit harder with student loan delinquencies, and delinquencies disproportionately affect African American populations.

A few key takeaways:

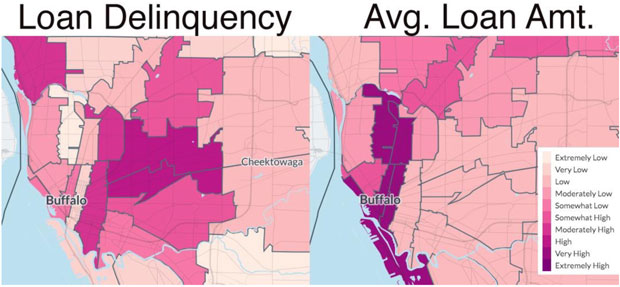

More debt = less frequent delinquency

It seems counterintuitive: The more debt you take on, the less likely you are to miss your payments.

WCEG provides an explanation for this phenomenon. First, the people who take on the most debt tend to be graduate students, who face a much friendlier labor market than those of us with simple undergrad degrees. They tend to be whiter, which means they don’t face the same kind of hiring bias that people of color do. And they tend to come from families that are wealthy enough to help them out if they’re in danger of becoming delinquent on their debts.

On the other side, people who borrow less often can’t count on the same kind of privilege or safety net. With less ready access to credit (something very much tied to race), they’re more likely to fall into exploitative loan arrangements.

Perhaps most unfortunate of all, these students are more likely to attend for-profit colleges. which tend to prey openly on low-income, minority, and veteran students. For-profit colleges tend to have poor graduation and job placement rates; in the worst cases, they’re schemes which enable institutions to gobble up financial aid money while providing worthless educations to vulnerable populations.

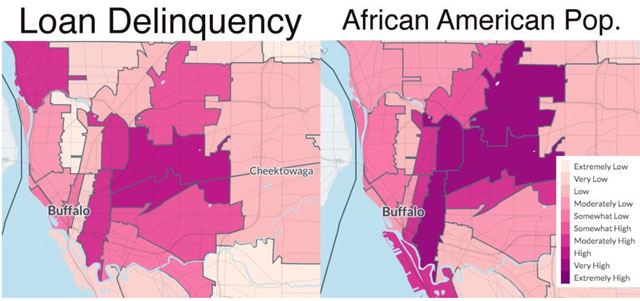

Even when you control for income, race matters

WSEG found that, across the country, ZIP codes with higher African-American or Latino populations had much higher loan delinquency rates.

“Wait!” you might say. “Race and income usually correlate too. How can we be sure this isn’t a matter of income?”

Sort of a covert attempt to derail, but we’ll go with it. WSEG controlled for income and found that this racial element didn’t necessarily cut across all income levels. High-income ZIP codes, regardless of race, had low rates of delinquencies. In lower-income zip codes, there were also low rates of delinquencies, likely because residents couldn’t afford to borrow money to go to college if they wanted to.

In middle class ZIP codes, though, race correlated with greater delinquency rates, reflecting a long history of structural racism in the US.

Education is often lauded as the key to social mobility for people looking to break into the middle class, and student debt is often perceived as investment in the future.

With every investment, though, there’s risk: In this case, the risk of not being able to pay back your loans. African-American and Latino families are much more likely to fall victim to that risk. Decades of racist practices, like redlining, mean that those families are much less likely to have any sort of financial cushion to fall back on if things don’t go exactly right.

On top of that, things are much less likely to go exactly right for non-white populations. African-American and Latino students are much less likely to complete college and less likely to apply and be admitted to prestigious institutions.

Those populations are also more likely to be preyed upon by the worst kinds of high-cost creditors.

Even after graduation, there are plenty of studies out there that show that, despite laws to the contrary, minority populations face persistent hiring discrimination.

Middle-class African Americans and Latinos, then, face much stiffer odds than white peers in the same income bracket when it comes to paying off their student loans.

Even non-delinquent debt can be stifling

There’s a lot of info out there about the negative effects of saddling a whole generation of highly-educated citizens with unmanageable debt.

Even as higher education is supposedly necessary for securing a decent life for yourself, student debt erodes the middle class by making it increasingly difficult to attain a middle-class income and do middle-class things like buy cars and houses. It also contributes to widening income inequality: According to Pew Research Center, young adults without student debt had seven times the net worth of young adults with debt.

That’s all well-documented. What I want to talk about are the political consequences of turning millennials into a generation of debtors.

Andrew Ross’s Creditocracy spells this out very clearly. According to Ross, “the loading of debt on to all and sundry has proven to be the most reliable restraint on a free citizenry in modern times” short of armed repression.

The basic contours of situation are these: Neoliberal governing pushes the costs of social needs like education, medical care, and housing onto individuals, who more often than not have to turn to debt financing to afford them.

This is where your uncle chimes in and mentions that taking on debt is a choice—no one forces you to sign up for that credit card or take on student loans.

Sure, fine. Technically, he’s correct. But in a society where the costs of basic social goods fall directly on the individual, where the prices of those goods have inflated far beyond what most of us will realistically be able to save in a timely fashion from honest labor, and where almost every institution that could help us has the incentive to guide us into a lifetime of debt servitude, what do you expect? That sort of armchair moralism is idiotic and unproductive.

Propping up society with individual debt would be regrettable but easier to stomach if these were one-time debts taken on, paid off, and left in the past like a rite of passage. The credit industry, though, thrives on “revolvers,” the folks who can’t afford to pay off their balances in full and who accumulate debt just to keep their heads above water. Revolvers now make up the majority of debtors. Why else, when you’re swimming in credit card debt, would Discover keep filling your mailbox with offers for more cards?

Federal student loans aren’t much better than debt to private companies, and in many cases, it’s worse. Senator Elizabeth Warren recently made headlines by pointing out that the government makes a huge profit on student loans—well over $50 billion. Even as more borrowers become delinquent on their debts and default, the government still rakes in late fees and penalties, buoyed by the fact that student borrowers lack bankruptcy protections.

As Ross points out, even though the governments profits on student loans are astronomical, very little of that money actually gets funneled into education. More often than not, we borrowers are subsidizing the nation’s militarism, bank bailouts, and our legislature’s dangerous, small-minded hunger for slashing government programs in the name of the deficit.

On top of that, the government has cleared the way for student loan interest rates to continue to rise even as most other borrowers are enjoying some of the lowest interest rates ever recorded, and tuition for colleges public and private continues to rise every year.

Like I said above, this is not just a financial problem: It’s a dire political problem.

Ross traces the genealogy of this political dimension back to 1975, when the Trilateral Commission (a favorite target of conspiracy theorists) released a report called “The Crisis of Democracy.” Troubled by the activism of the 1960s, the Commission reminded the leaders of the free world that “the effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and noninvolvement on the part of some individuals and groups,” especially students, who were becoming more educated, less employed and increasingly inconvenient to deal with as a political force.

Luckily for those in power, debt was on the rise, especially student debt. Instead of breeding educated citizens with enough time on their hands to organize, colleges pushed out students already underwater in debt, who had no choice but to attempt to break into the labor force as quickly as possible and work twice as hard just to give themselves some breathing room.

As Ross puts it, “in a world where debt service forces us to work longer and harder in the present, and where the future is already eaten up by compound interest, the labor of imagining, let alone creating, an alternative society is easily set aside. After all, keeping the repo man from the door is already onerous enough.”

It makes logical sense. How could we find the time or energy to change things when we’re working more to stay afloat? We live in a society where social goods are re-imagined as shoddy private investments so that organizations that are already exceedingly wealthy can continue to extract rents from us just for staying alive, but how can we resist that system when we’re yoked so tightly to it? How can we take on any additional risks, try anything new, take any unnecessary chances when we’re all one bad day away from our foundations caving in?

And even if we had the energy, we might lack the political imagination. A better, more just society seems like a fairy tale; our monthly payments are very real. To steal a cliche from Fredric Jameson, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

Then again, it seems obvious: Something must be done.

More Back to School info:

|