Ogilvie Unites Divided School Board

When the Board of Education majority released its proposal ahead of its latest meeting, the fate of the four out-of-time schools looked all but assured. The four community-sourced design plans would be scrapped, while at least two institutions—MLK and Riverside*—would be handed over to charter schools—Health Sciences and CSAT, respectively—for the beginning of 2015 classes.

The inevitability seemed somehow even more inevitable after the majority voted down a separate plan presented by superintendent Donald Ogilvie. The future was written.

Then board president James Sampson bumbled a point of order, igniting a shouting match between majority member Carl Paladino and the board’s legal counsel. Instead of voting on the majority resolution, which would have doubtlessly passed 5-4, the board had to take five minutes to let tempers cool.

By the time the meeting reconvened and the point of order was settled, serious discussion about the majority’s plan had begun.

What happened next was truly unbelievable.

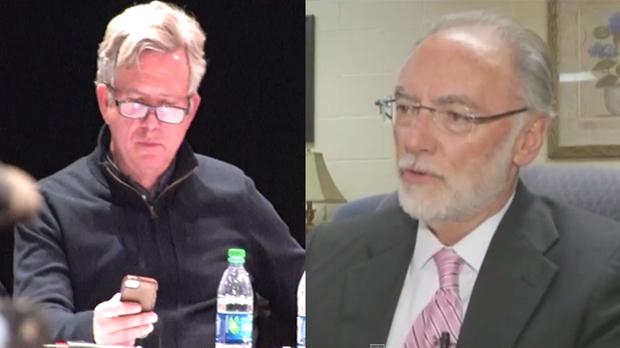

Larry Quinn took over in the back-and-forth regarding the majority’s positions; yet, the proposal was too divisive to spur any meaningful debate, so the suggestion was made to work off of Ogilvie’s plan. Quinn assented. Next, he, the board minority members, and Ogilvie began adding language to the latter’s plan in order to turn it into something that they could all get behind.

Like that, the majority had dumped their own proposal. And, in the end, a 9-0 vote had revived Ogilvie’s plan with a few addenda.

Once negotiations over the superintendent’s plan began, those present got a deeper look into the inner workings of the board majority. Paladino, perhaps exhausted from his shouting session, slumped in his chair staring into his phone. Patricia Pierce became a voice of reconciliation. Quinn led the negotiations, while Jason McCarthy satisfied himself with occasionally repeating points made by Quinn.

The proposal by Ogilvie deserves a longer look. Among the major points are to reject all four charter proposals and focus on expanding existing district programs into the phase-out schools, thereby short-circuiting the need for state intervention. The state would have had to approve any turnaround plans presented by the four out-of-time schools—MLK, East, Lafayette and Bennett—as well as any presented by charter schools.

Prior to the majority voting down Ogilvie’s proposal, minority member Sharon Belton-Cottman placed the spotlight directly on him. She said she was worried that after he was appointed by the majority he would become their instrument. She said that he came to the district without even a meeting with the minority members. She said she wasn’t sure of his character.

“Was he going to be his own man?” she asked, before answering her own question. “This resolution speaks loudly: He is his own man, and I want to commend him.”

Belton-Cottman’s sentiments were later echoed by the other four minority members—Theresa Harris-Tigg, Barbara Seals Nevergold, and Mary Kapsiak.

“He’s not your boy,” Belton-Cottman added by way of amplification, turning to Quinn, “and this ain’t a hockey game.”

Ogilvie’s recommendations, it was suggested, have put him at odds with the majority, and, as Belton-Cottman noted, there’s a rumor circulating that they may cost him his job.

When asked after the meeting whether he expected to be around for much longer, Ogilvie quipped “past April 1st,” a date which had earlier been floated as his expiration date.

During the meeting, he was less diplomatic, digging in and holding his ground, scrutinizing the viability of the majority’s proposal. “I question its feasibility and [the] ability of my staff to implement it,” he said.

A major issue arose regarding the proposal’s use of the verb “direct.” Is the job of the board to tell the superintendent how to set policy, or have the positions been inverted?

“I’m concerned about what the resolution does to the role of the superintendent,” Ogilvie observed. Nevergold wondered whether the proposal indeed presumed to give directives to Ogilvie.

“Yes, this directs the superintendent,” Quinn stated.

In response, Nevergold suggested that, in the instance that the super and his staff (who would be responsible for implementation of the proposal) should be compromised by its implications, there would be a “problem.”

“We’d have to do something,” responded Quinn vaguely, but with no one questioning the meaning of the last word in the phrase.

The majority leader had openly announced that if Ogilvie didn’t go along with the proposal, he’d bury him. Yet the super stood tall, gave several heartfelt compliments to his staff, and proceeded—with timely contributions from the tenacious minority members—to make his vision for Buffalo Public Schools a reality.

This is all by the way of expressing a simple fact: Nobody came out of the board meeting looking more impressive than Ogilvie. His proposal, which, at 10:15am, resembled a corpse about to be sullied with several shovels full of dirt, was, by 1pm, living and breathing and walking around room 801 in City Hall.

Some quick hits from the superintendent’s post-meeting interview:

What will happen in the four out-of-time schools?

“Those buildings will continue to phase out, but into one of them, Bennett, we will move Middle Early College. We will continue to develop plans at Lafayette, and in the meantime, most likely put a newcomers academy in there and build around that. With East High School, we will continue to plan, and the intent is to create a better definition, a more appropriate definition for alternative education, and use East High School. And then MLK…is…the primary location for an annex to the Visual and Performing Arts, although that’s not settled.”

What about the charter proposals?

“At this point there are no specific plans for a charter to occupy a building…although the possibility always exists, but not in any of the four out-of-time buildings.”

What’s happening with the lawsuit filed with the Office of Civil Rights?

“We absolutely will not make any binding decisions about school design, location, or enrollment without a very careful consideration of the report and recommendations by Dr. Orfield…We haven’t closed off any options, which was my concern.”

What should the community expect from the BOE in the near future:

“I’d said earlier that this is the end of the beginning, and that we will have out-of-time schools in each of the next two or three years. One of my hopes—part of the intent of my resolution—is to give us a model for planning for doing the right thing. To always have the opportunity to consider options…to not have them denied…to recognize that all of these things take time and good faith.”

*Riverside has not yet been distinguished as a “failing school,” but the proposal treats it as such. Of the other two out-of-time schools—Bennett and Lafayette—Bennett was to be turned into a mash-up of Middle Early College, City Honors and Hutch Tech, while Lafayette’s fate was not addressed in detail.

Shane Meyer reports on education and New York State policy.