Lori Waxman: The 60 wds/min art critic, Volume 3

For three days in November, art historian and critic Lori Waxman installed herself at the Burns Building on Huron Street and received local artists seeking a review of their work. Each artist’s appointment lasted 25 minutes and resulted in an instantly rendered, signed review. Thirty artists visited Waxman, who describes her 60 wrd/min art critic project as ”an exploration of short-form art writing, a work of performance art in and of itself, an experiment in role shifting between artist and critic, a democratic gesture, and a circumvention of the art review process.” Last month we published 10 of these, then eight more. Here are the rest.

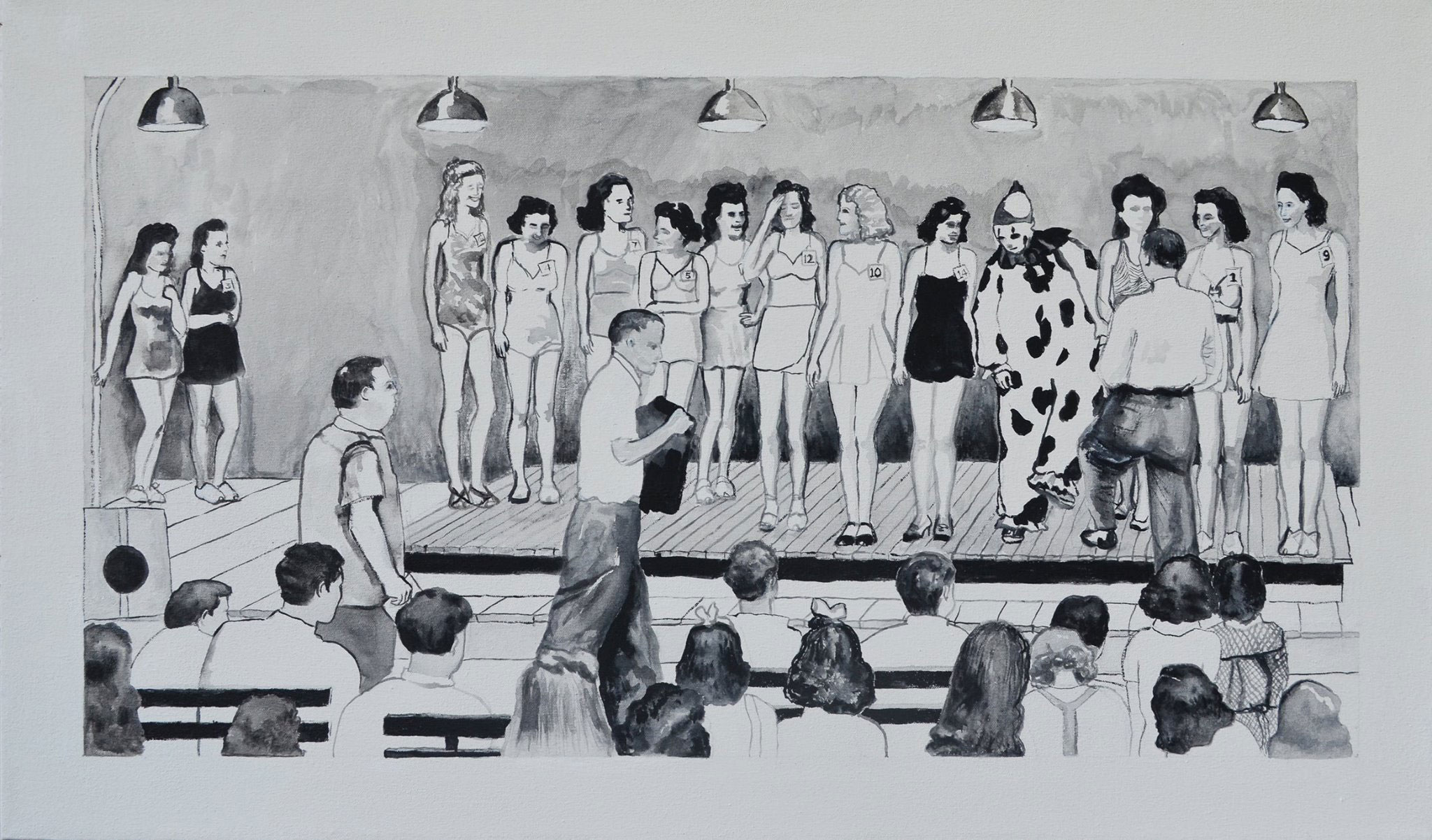

MARY WYRICK

Old photographs bring on powerful surges of nostalgia. They’re hard to resist, as are fantasies of how good life was back then. Mary Wyrick, having discovered among her parents’ belongings pictures of the 1941 Miss Mayfair beauty pageant at the textile mill in Burlington, North Carolina, where they lived and worked, decided instead to paint them. Painting can interrupt romantic visions of the past that ignore what we now know to be true: that textile mills and company villages were an extension of the plantation system, that beauty pageants demean and objectify women. Wyrick’s ongoing series of paintings don’t reveal this knowledge directly so much as they make space for the critical viewer to project it. Gone is the glossy, untouchable reality of the camera, present instead is the raw, thoughtful attention of the painter’s brush.

TONY YANICK

In a collaboration with the poet Rafique Washington, Tony Yanick and Adrian Alecu produced a drifting documentary about contemporary Cleveland, complete with empty lots, gentrifying parcels of downtown, black street preachers, abandoned buildings, and oblivious white wedding-goers. In their segment of The Fixers (a larger series produced by Kate Sopko), Yanick and filmmaker Robert Banks, Jr. portrayed the young black activist Naudia Loftis and her family and friends in the Kinsman neighborhood, where too many black kids are getting killed. Regretfully Yours, K feels like something else entirely, a filmed theatricalization of the writer Franz Kafka’s deep anxieties and romantic correspondence. Today, however, with the recent presidential win of Donald Trump and the related rise of the far right, it all comes horribly together. Milena Jesenská, a woman with whom Kafka exchanged letters, died in a Nazi concentration camp. This country just elected its Hitler. Cleveland isn’t going to get any better. It’s all going to get far, far worse. Yanick had the eerie prescience to make films about it ahead of time.

KARI ACHATZ

Peeling paint, broken bricks, graffitied walls, and overgrowth may not seem like obvious elements for a series of beautiful photographs, but in Kari Achatz’s “Disremembered” they amount to just that. Buffalo’s long-abandoned Central Terminal Station, an Art Deco masterpiece out of use since the mid-1950s, serves as subject in Achatz’s three-part study. Close-ups reveal walls mysteriously punctured or textured like colorful animal skins; black-and-white long shots set the desolate scene. The ruin, a stable photographic category established by masters like Robert Polidori, holds many attractions. First it offers a critique of architectural abandon, whether due to the vagaries of capitalism and progress or to environmental disaster. Second comes appreciation, not a cynical love of destruction itself but rather of what the late Leonard Cohen once described in song: “There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.”

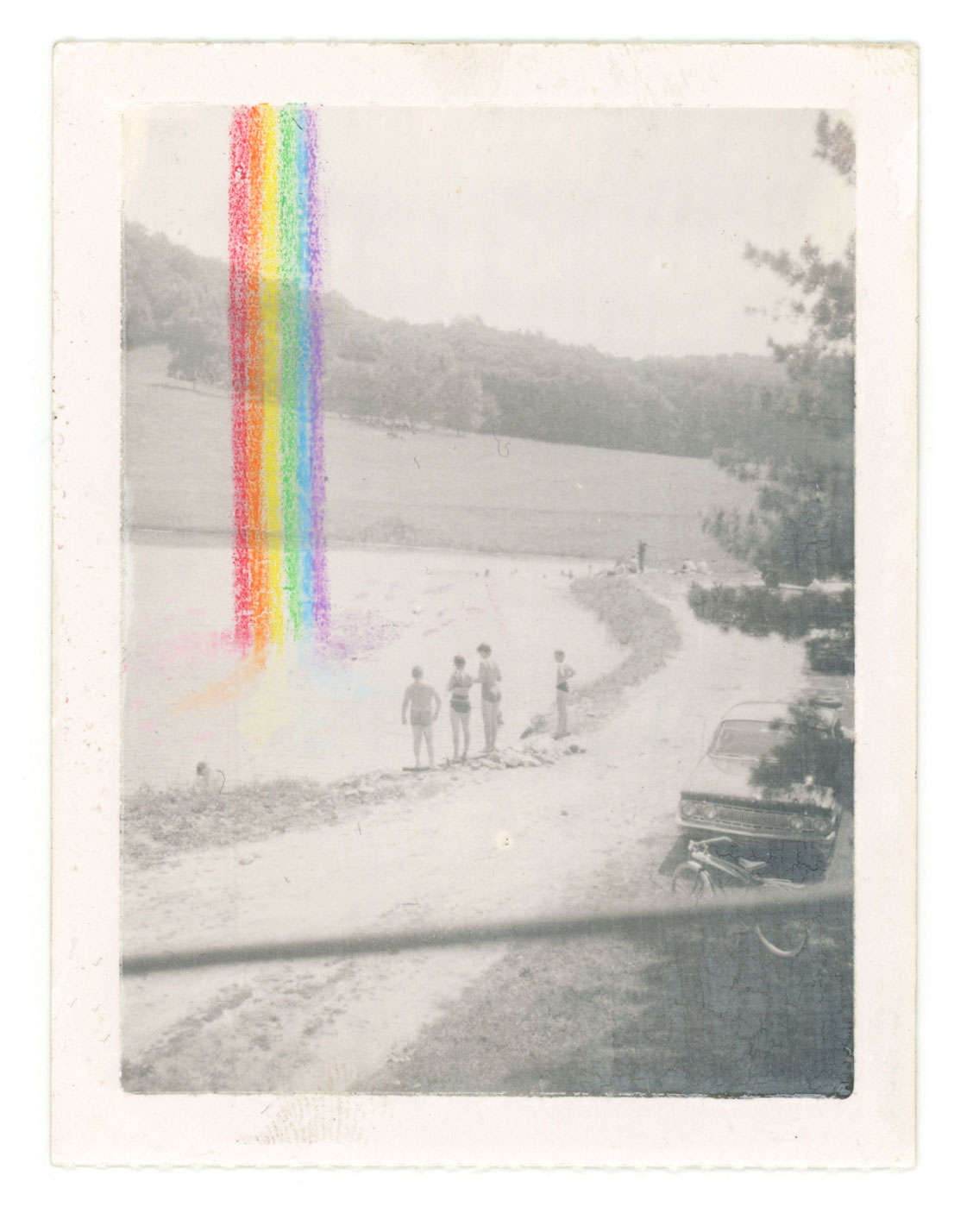

CASSANDRA OTT

Cassandra Ott paints rainbows on top of found vintage photographs: families at the beach, couples and individuals posing stiffly, houses in the landscape. They enchant, far beyond what the application of spectrums of color ought to do, given their appeal to elementary school girls, my seven-year-old daughter included. Rainbows may be the single most commonplace of marvels. They appear in the sky after a storm, or when sunlight shines through the lawn sprinkler, and we all learned in science class how the mechanics work. And yet, who can resist them? They are wonder, pure and simple. When Ott applies their six bands of color so that they seem to burst out of a black-and-white lakefront or off the top of a children’s teepee, from the heads of a group of women graduates or out the hands of a child digging in the sand, she recognizes the potential for glory inherent in daily life.

RICH TOMASELLO

From mock children’s toys in the form of sparkly pink gas masks and armed teacher figurines to a see-through backpack filled with plastic pistols and grenades, the artwork of Rich Tomasello cannot be called subtle. Nor can its messages against gun proliferation, the gendering of children, and the weaponizing of education be mistaken for anything but strong and painfully necessary social critique. Flight, Tomasello’s latest, is something quite different: a bevy of life-size female figures, nude, sculpted from plaster, and suspended gracefully in the air, their faces blank but serene. What they have got to do with the rest of his work, apart from the gas masks some sport, may be indicated by the visceral longing I experienced upon seeing them afloat: up in the sky is the only place I want to be right now, above the noxious atmosphere of this country and its new president-elect.

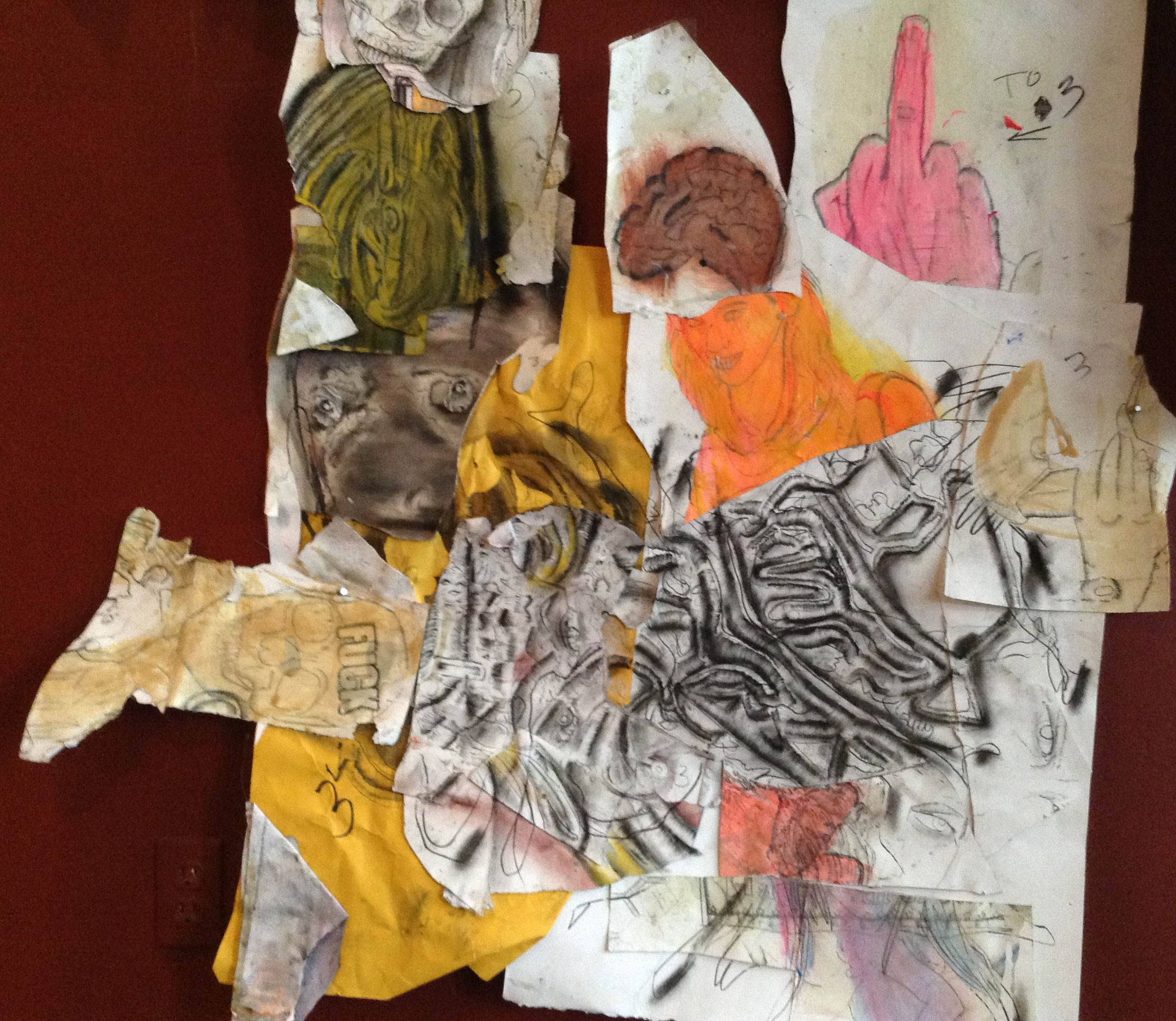

KURT VON VOETSCH

The subconscious remains a mystery until it bursts forth. When it does, it can be grotesque. Kurt Von Voetsch, creator of abject performances involving pig and cow parts, animal fat, body cages and corncobs, engages with his own publicly and fearlessly. In recent years, after a diagnosis of brain cancer and subsequent surgeries and medications, Von Voetsch has used his splayed open mind and memory as fodder for a series of terrifying drawings that mix body parts, pornography, the desecration of antique bookplates, and skilled draftsmanship. It is hard to have surgeons cut open your body to remove some of its parts, but it may be harder still to accept that inside you malignant tumors have been growing. When they are gone, can you still be whole?

TIMOTHY BROOKS

In our post-media age, it’s not uncommon for a conceptual artist to make paintings or a photographer to create sculptures. At the art school where I teach, most of the students in the painting & drawing department currently make installations. Timothy Brooks, who takes digital photographs, manipulates their original elements, and then prints the resulting image on textured watercolor paper, finds himself right at home in this new world. Brooks is a painter who uses the tools of contemporary photography to make what amount to traditional paintings. It isn’t always worth sticking with medium-based categories today, but in the case of Brooks it allows the key qualities of his work to be isolated: color, texture, brushwork—yes, brushwork. In works like The Beat Goes On, Brooks takes photos of nothing special and turns them into something brushy and impressionistic, full of gestures that reach to the edge of the composition. Camera lenses don’t see this in the world, but the painter’s eye sure does.

HOPE MORA

Imagine picking up a tabloid from the newsstand and finding it to be devoid of text, with only blank off-white space surrounding the colorless photographs that float on its pages. Imagine watching a segment from the nightly news without sound, playing over and over again on a hypnotic loop. How would you know what you were seeing? How would you know what it all meant? In a newsprint edition and a video diptych, Hope Mora challenges the viewer’s ability to make sense out of mediated—and, in a sense, de-mediated and re-mediated—images that range from migrant farm laborers at work picking vegetables to oil derricks pumping away, from a bored kid in a classroom to heavily made-up Latina teenagers in hoodies. The pictures aren’t a rebus whose solution reveals a hidden message, but rather a prompt to learn to read the world around us more critically. Otherwise we might succumb to a depleted sense of Pues, Asi Va La Vida (That’s How Life Is)—the title Mora gave her video.

JAMES HICKEY

In 1952 the critic Harold Rosenberg coined the term Action Painting to describe the work of artists like Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. If only history had stuck with his designation, which so explicitly addresses their all-over gestural canvases as the record of a physical event, we’d have the perfect category into which to nestle the work of James Hickey. (Add to that Nikki de Saint Phalle’s gunshot paintings and the bodily work of the Japanese group Gutai, and voilà, art history remix!) Hickey’s thick, encrusted paintings bulge with edge-to-edge color and texture, and while some give a hazy sense of flaming fire or reflecting water or even landscape, primarily they are the hard evidence of physical exertion. On the reverse of one whose pinks, blues and reds might’ve come straight from the tube, Hickey writes about transfers of energy. Indeed, more than anything else, that is what he produces: transfers of energy from person to canvas through the gesture of painting—with brush, with trowel, it hardly matters. Somehow the paint must get up there, and there’s a body that needs to do it.

BRANDAN ZYCH

Why make art? There are all kinds of reasons, from the social and the political to the economic, the expressive and, of course, the aesthetic. Some prints by Brandan Zych suggest the addition of a sixth possibility, the technological. In Atlas and Extruder Zych produces a watercolor drawing, scans it, then runs it through various programs like Photoshop and Corel Painter, printing out end results that little resemble their origins, or each other. The former registers as a murky, moody corner of sky; the latter as an explosion of infinite light and glass shards. Zych controls these outcomes just so much, and so it seems only right to give credit to his artistic collaborator: the computer.

KATHIE ASPAAS

Propaganda is biased information put out into the world to change and influence beliefs. Printmaker Kathie Aspaas makes what she calls “soft propaganda,” something a little less imperious, a lot more forgiving. A diehard capitalist might not observe that The Root of All Happiness, an amorphous agglomeration of three grayscale bands, is printed on paper handmade with shreds of money. If he did notice, he might not get the ironic critique, either. Why be so equivocal? A second work of Aspaas’s suggests a possible answer. At the center of a vortex collaged from found photos of rocks, a barking dog, and scraps from other projects sit two men in a cockpit heading far off into outer space. The title, Exiting the Dogma System, promises some kind of hope ahead, though it might require leaving this planet.

KRISTINE MIFSUD

My late grandfather owned a tire shop that specialized in retreading tractors. I can imagine Kristine Mifsud finding nearly all of her materials in the back of his garage, and I can picture his appreciation of her vision; he too was a sculptor. What Mifsud does with small bits of used metal and rubber is transformative, though in a way opposite that of a traditional sculptor, who must carve away stone to find the shape that lurks within. Mifsud accumulates, adding this piece and that until something elegant and evocative—and entirely new—emerges. A red rubber pocket with the word FULLER fills with narrow coils and tubes, all of them relieved to finally be together. Two small, heavy canisters wear rubber caps that join their tops, a pair meant to be. Best of all is a thin hole-punched chit hanging from a length of nylon, suspended between a washer, a rubber oval and another metal scrap: the curve in that string is a catenary. Jasper Johns painted an entire series about them. It takes an open mind and a finely tuned vision to find the makings of high art in the gutter