Lori Waxman: The 60 wds/min art critic

For three days last month, November 11-13, art historian and critic Lori Waxman installed herself at the Burns Building on Huron Street and received local artists seeking a review of their work. Each artist’s appointment lasted 25 minutes and resulted in an instantly rendered, signed review. Thirty artists visited Waxman, who describes her 60 wrd/min art critic project as ”an exploration of short-form art writing, a work of performance art in and of itself, an experiment in role shifting between artist and critic, a democratic gesture, and a circumvention of the art review process.” Here are 10 of those reviews; we’ll publish more of them in the coming days and weeks.

virocode

What is normal? Normal is stability, predictability, calm. It is unidirectionality. It is clean and smooth and same. It is cars driving forward, explosions diffused, viruses contained, spills wiped up fast. Sounds great, right? The artist collaborative virocode has been making work since the late 80s that challenges the scientific reality and assumed desirability of normal. Who wouldn’t want a Siamese car? virocode built one that drives street legal. How to resist the beauty of small explosions? virocode took split second photos of their brilliant sparks. Isn’t gushing liquid stunning? virocode built a frozen waterfall of poured acrylic and photographed bursting water balloons. But what of contagious diseases, what of visible growths on the body—surely there is no place in the aesthetic pantheon for them? In the installation “ In which nature abhors a vacuum,” virocode embraces these forms of bodily difference, too, banishing fear and welcoming uncertainty in extremis.

KRISTINA SIEGEL

Our world is made of heavy structures and opaque objects. Things must be solid to be valuable, but so much density can be stultifying or misleading. With time, monuments lose their purpose, buildings crumble or renovate, dinner parties break up, people die. With a scenographer’s ability to move between two dimensions and three, and to appreciate the theatrical suggestion of place, Kristina Siegel rights this wrong. The artist recreates obelisks, walls, chandeliers, tables and tableware, even tombstones out of silk organza and thread, rendering them as ghosts of their former selves. Ghosts move in the breeze, they make way for new constructions, they can be seen through, not just around. They hover, diaphanous, never quite disappearing but always aware of their own fragility.

VINNY ALEJANDRO

Vinny Alejandro paints murals that bespeak an appreciative vision of the world in which he lives. For a local fitness center, he spread a glorious sunset behind the shadowy skylines of Buffalo and far-off Niagara. At Derrick Industries, he imagined a typical American Main Street as it used to be, full of bright signage, busy small businesses and cars with tailfins. On the outer wall of AmVets, a veteran’s organization, he pictured a proud, orderly scene of military vehicles on land, air and sea. These compositions are simple and straightforward, clear about what they promote as valuable: nature, industry, hard work, democracy. But it’s the dilapidated shed that Alejandro painted behind his house in the regenerating Old First Ward that reveals the tension underlying so much of what orders his murals: covered with a sunshine background and a giant purple orchid, the shed remains in such poor condition it’s practically unusable. A coat of paint isn’t enough, it isn’t, though it’s something.

ALICIA MALIK

I have always been drawn to butterfly and insect collections, the kind found in antique stores, where minuscule bodies are pinned in rows and neatly framed. Alicia Malik’s paintings belong to this category of study but they differ importantly: rather than tack the dead creature to a stark white mat board, as if it were a perfect graphic object—though, truth be told, they make marvelous objects—she treats it as an empathetic subject, in all its lonely lifelessness. Malik finds craneflies and hornets already deceased, stiff on windowsills, and makes careful studies of them in watercolor or paint. The results are half portrait, half still life. Curiously, they don’t all look obviously dead: a honeybee seems to be resting cutely on its side, a beetle might be on its way somewhere. Stranger still, most are surrounded by nebulous non-space. Entranced with these tiny arthropods, one wishes for a bit more detail, but appreciates the great care they’ve received in memoriam.

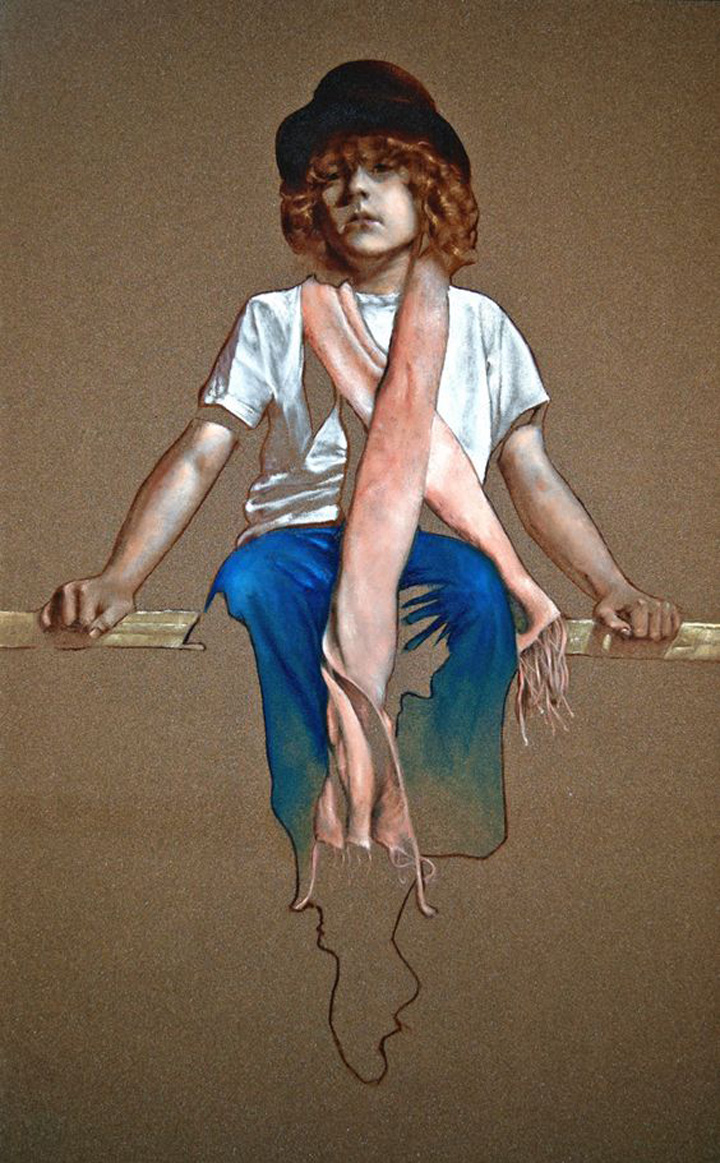

GREG KUPPINGER

The adolescent boy seated at the center of a tall painting by Greg Kuppinger stares back at the viewer with a look somewhere between innocence and knowingness. Detailed in oil with great care and realism, the folds of his white T-shirt crumple crisply, the curls of his golden brown hair tumble softly, the fringes of his long peach scarf twist silkily. Despite the veracity of his upper body, though, the boy’s lower half won’t stay intact: his legs, encased in jeans, dissolve until finally, all that’s left is an ocher painter’s outline in place of his toes. Perhaps he’s wiser than his years, this kid, and he knows what Marx once wrote to be true: all that is solid melts into air. We haven’t always been here and we won’t stay forever. It’s a hard truth, and one that Kuppinger’s medium bespeaks viscerally. He paints like an Old Master, or at least like Balthus, but he paints on sandpaper. The visual effect is a learned scumbling, the tactile one painful.

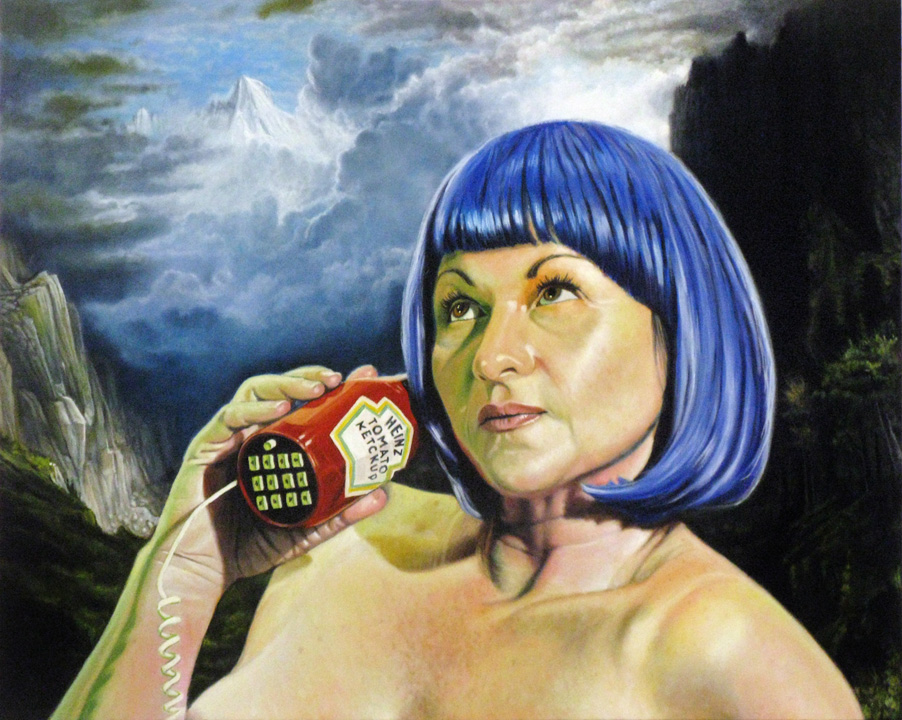

BRUCE ADAMS

Portraiture constitutes one of the great traditional categories of painting. Before the era of mechanical and now digital reproduction, it stood as a primary means for asserting the importance of a person and his or her—though mostly his—character. Bruce Adams is a portrait painter for today, proceeding with all the skill of past painters and a hell of a lot more fun. In his meticulously rendered canvases, friends and acquaintances collaborate in the creation of pictures that tap their fantasies, tastes and projections with evident pleasure. A woman in a blue bob talks on a Heinz ketchup bottle telephone against a romantic landscape of peaks and valleys; a bottle-blonde man in fishnets and heels tussles with a vacuum cleaner against maroon cliffs; a silver-lipped lady in satin gloves, star glasses and purple antennae brandishes plastic uzis against a serene grove of trees and sky. This is total portraiture: not just how we wish to be seen but how we really are, visible and not, wrinkles, fetishes and all, rendered picturesque by a capaciously generous paintbrush

POLLY LITTLE

I do not love fables, preferring the inanimate elements of nature to be anthropomorphized. A talking rock beats a talking fox in my book. In Polly Little’s compositions, animals do not speak but they might as well, so intently do they occupy her painted canvases and carved wood blocks. The blocks are leftovers from the process of making prints, which Little exhibits as well, and normally they are just that, leftovers. Little does something novel with them that also feels novelistic, recalling the style of Swedish children’s book author Jan Brett. Affixed to the tops or sides of same-size canvases, the blocks act as marginalia, bringing different animals in different registers together into the same tale: ram, rooster, and aye-aye join with gecko, bison with beaver. What’s the moral? They make fine prints too, including a witty one of those notorious wood chompers, beavers, who might have had a hand—or tooth—in making their own picture.

KURT TREEBY

Standing on the 300 block of East Superior in downtown Chicago, a lover of modern architecture could cry. Bertrand Goldberg’s magnificent vertical clover of concrete, the former home of Prentice Women’s Hospital, is nowhere to be found, demolished a few years ago to make way for a dull expansion of the Northwestern medical campus. Kurt Treeby offers something with which to dry those tears and have a chuckle besides: a tissue box cover in the shape of the lost building. Using plastic canvas and acrylic yarn, Treeby has taken a kitschy craft and raised it up high. “ Disposable,” as he’s titled his series, pays tribute to Marcel Breuer’s jagged Whitney, one of SITE Inc.’s Best Products showrooms, and William and Tsein’s American Folk Art Museum, among others. We tend to think of architecture as something permanent but it isn’t, even the best of it. The sharpest irony of Treeby’s project is the ability of the lowliest craft to offer so fitting a memorial to the highest of the arts.

FOTINI GALANES

People are rarely all that they seem. You cannot tell by looking at my son that he has tumors mottling his right leg. You cannot tell by looking at me that I had a mastectomy. You cannot tell by looking at Fotini Galanes that she is a burn survivor. Nor are artworks always all that they seem. You cannot tell by looking at Galanes’s swarming, swirling, bulbous abstract drawings, rendered in sharp graphite on unforgiving clayboard, that they are her way of exploring body deformation and grotesquerie while letting go of the human bodies that suffer them. But you can know this by talking to Galanes, who prefers to work in coffee shops, where her art making often draws curious onlookers. The moving stories told to her in return for her own then make their way onto paper cups, testimonial to just how commonplace difference really is.

CHENG YANG LEE

In their zeal to revolutionize everyday life, the Situationist International vowed to abolish boredom, lifeless architecture and work. There may be another way. Cheng Yang Lee makes videos of snow fluttering and escalators going up, of a cat lounging as relaxed as can be, of balloons caught in a tree, of a plastic deli bag blowing through an intersection. He takes hundreds of pictures from his apartment window, of the not-so-much that goes on out there, of the light glinting on the vertical blinds, of the streetlights glaring beautifully in the dark. He builds an altar to the stereotypical stuff of life in the United States of America: a bottle of coke, fries, a burger, an apple, a donut and coffee, roses and pennies, the welcome pamphlet he received when he emigrated here from Malaysia. He makes a calendar that marks the progress of daylight and an agenda that tracks moonlight; his partner uses them, but little happens. Bored? Boredom is on you. Anything can be interesting, even nothing much.