Do Copiers Dream of Electrostatic Sheep?

It seems counterintuitive that there should have been any great interest in the photocopier as an instrument for making art. The copier itself—a device designed to generate sameness, increase efficiency in organizations and to thereby make virtues of sameness, efficiency and organization—appears antithetical to those things we associate with the production of works of art: the development of idiosyncratic techniques, the formation of schools of theory and practice, the opening of spaces of experimentation and the making of difference.

But like all technical processes—despite their presentation as closed systems—the process of electrography (the original given name of the Xerox process) admitted manipulation.

Use of the photocopier in American works generally expressed itself in two modes: the San Francisco-based cut-and-paste collage technique (hence the titular ‘fast, cheap and easy’); and the Rochester-based process-oriented technique, centering on experimentation with methods and materials. The first group was largely comprised of artists working outside of institutions, including “a loose confederation of artists under the direction of Barbara Cushman (1945–2014) [who] produced a series of copy art calendars known as the Color Xerox Annual from 1980–1984,” according to Robert Hirsch, who along with Kitty Hubbard, Klaus Urbons, and Tom Carpenter curated the show. The second group was largely comprised of artists affiliated with the Visual Studies Workshop, George Eastman House and Rochester Institute of Technology.

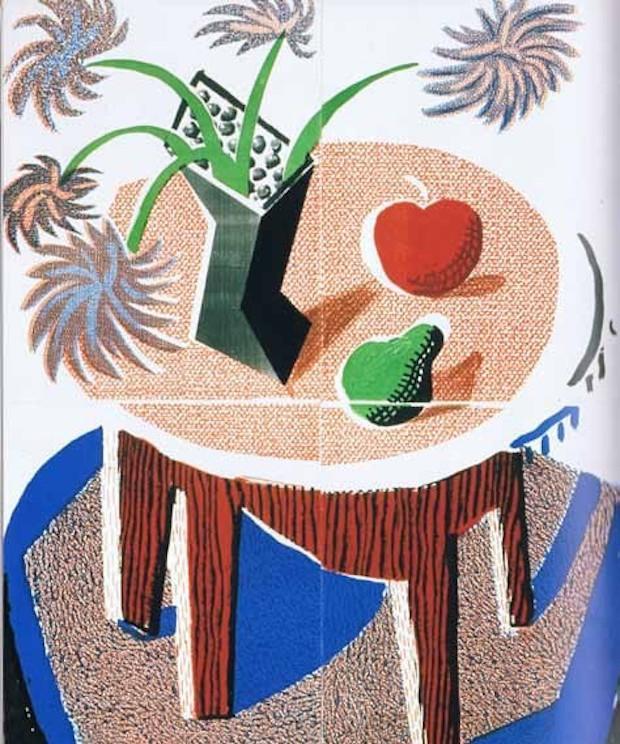

These two approaches reflect alternating focuses on the means of production and on the materials used in production. In the West Coast approach (featured in CEPA’s second floor gallery), artists used the procedure familiar to anyone who’s used a modern day copier, the complex workings of which are automated and invisible: press the button and whoosh out come hot copies. The use of material is similarly reductive: whatever will be copied must be flat; it must fit under the Xerox’s hood. Paper works best. These works, exemplified in the aforementioned Color Xerox Annual, tend to project economic, political, cultural and sexual anxiety—documentation of the bad time everyone seems to have had during the 80s. Yet, they’re executed with brio, incorporating the familiar style of Pop Art, while cutting it up, estranging it, re-presenting it as tho thru the lens of bad dream had well.

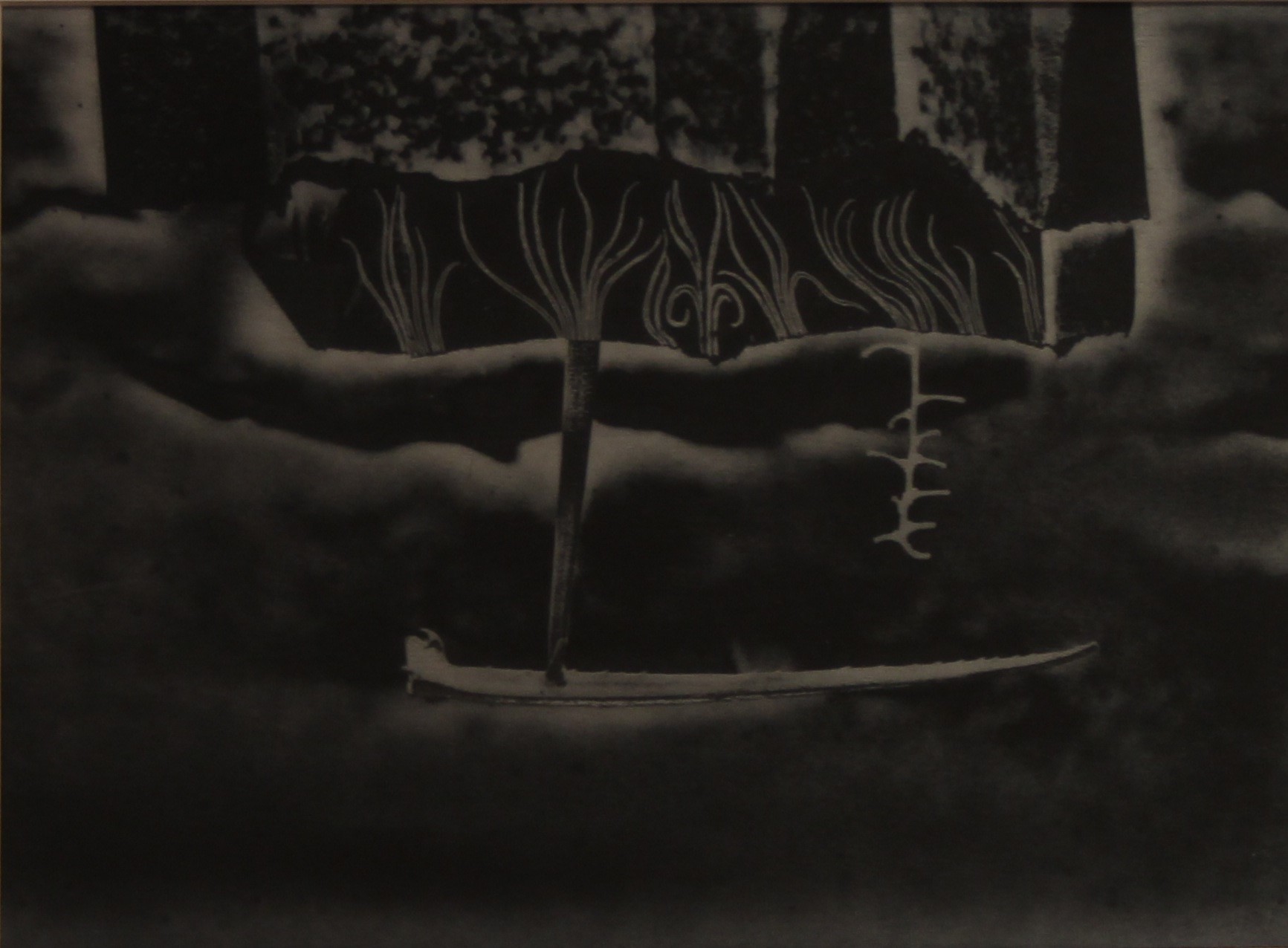

In the process-oriented approach, pioneered by Rochester-based artist Charlie Arnold, artists eyed electrophotography as techne not technology. If, in its business applications, the copier became more self-contained and inscrutable, then in its artistic applications, it would be broken down into its component parts, each presenting opportunities for intervention and experimentation. Co-curator Tom Carpenter, who taught a CEPA-sponsored workshop on electrophotography, demonstrated the practice using a 1950s model Xerox. A selenium plate is inserted into a Big Metal Box which zaps it with a positive electrostatic charge. The plate is then transferred to a large format camera. Snap! The areas exposed to light on the plate lose their positive charge, and the plate is placed back in the Big Metal Box into a drawer with dry toner and rotated. The negatively charged toner is attracted to the areas that have not lost their positive charge due to exposure to light. A piece of paper is laid over the the plate and zapped once again. Once removed from the plate the sheet of paper is placed in a small oven and the heat fuses the toner to the paper and gives the image the recognizable Xerox sheen. Each step, nowadays executable with the push of a button, invites recalculation, recalibration and rearrangement.

Charlie Arnold, “Untitled,” 1970.

The result is visually confounding: works that simultaneously bristle with the flattening sheen and heavy contrast of a copy, while retaining recognizable features of traditional artworks: depth of field, compositional integrity, gradients of light and shade, and most splendidly, texture. Arnold’s acolytes developed his original insight by integrating copies with other media (charcoal, pastel, print) and by incorporating electrophotographic works into other materials (fabric, glass). Keith Smith’s “Untitled” (1971), for example, features a hologram situated side-by-side with its photocopy, stitched into a pillowy, satin frame.

As Hirsch notes in his catalog essay, the “copy art revolution” was not limited to the East and West coasts of the States. It included a group of artists centered around Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany. While the American schools remained optimistic about the potential of Xerox technology, the European school is broadly more pessimistic but not in the bad way.

How does the photocopier distort time? is the question posed by Klaus Urbons’ video installation “12 Hours” (1987) in which Urbons photocopies a clock once a minute for 12 hours. After the copier runs off the image, he tacks it on a large wall which by the end is full. Hang on a second. We don’t experience time cumulatively but as loss. Time may seem to speed up or slow down, surely it never builds up—surely it never presents itself as a collection of each of its moments. Yet it is precisely the function of the photocopier to do so: to reproduce the past in the present without intervention, mediation or loss. Such is the aura of terror exuded by a photocopier immediately recognizable to anyone who’s worked in an office: of time as an endless, redundant accumulation.

The tactical mischievousness of the Germans is again brilliantly illustrated by Urbons, who curated the third floor of the show and whose ceiling-to-floor arrangement of four artists’ works [Vittore Baroni “Untitled” (n.d.), Guy Bleus “Ungültig” (1992), John Waszek “Untitled” (2017), Mari Lena Rapprich “Untitled” (2018)] is the exhibit’s highlight.

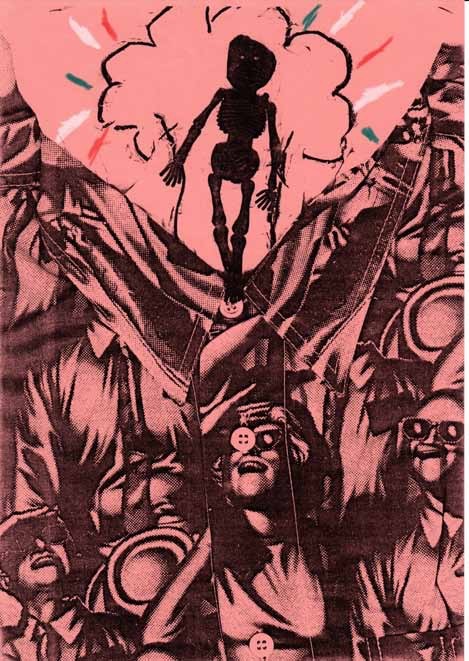

Baroni’s image tops the eight-piece cross-like arrangement: a skeleton enveloped in the silhouette of a mushroom cloud, emerging skyward above a crowd of ecstatic onlookers—a latter-day Ascension wherein the figure taken up into heaven is not one of future promise but future doom.

Forming the horizontal plane of the cross are Bleus’ photocopied rubber stamps (nice joke), a manual method of reproduction evoking the machine age, which play well off Waszek’s lithographs below (I think they’re lithographs I really can’t even tell what in them is photocopied). Both Waszek’s pieces allow the eye to linger over the heavily textured surface but eventually draw it to an indistinct central void. Waszek begs the question: what precisely has been reproduced?; Bleus coyly responds: advancing techniques of reproduction are merely a means of producing more efficient means of reproduction.

At the bottom, Rapprich’s tri-colored graph paper works descend past the baseboard, where the final one rests slouching halfway between wall and floor. The bleeding colors resemble a copy made with the cover half-raised—an interruption of the carefully engineered Xerox operation.

The assemblage can be read from top to bottom or from the bottom to the top. I prefer the first: Baroni’s image of ecstatic ascent, descending thru the frenzy and indeterminacy of reproduction, into the recycling bin. At the end of the day we don’t even get the perverse satisfaction which might accompany global nuclear destruction; instead, bored nearly to death (not quite, another frustrating irony) by the anxiety of always having to repeat what came before, we rest between wall and floor, blinking, buzzing, unable to decide whether to sit, stand or lie down. Thus the dual gesture of the Ascension (the departure and the return) is united in the figure of the depleted, depressed modern subject, who inevitably needs ‘a little pick-me-up.’

Vitore Baroni, untitled.

If the great technocratic dream embodied in the copier was to flatten the world, to make it more predictable, to make it the same everywhere, then the accomplishment of artists who took took up the copier as their tool, was to show that, notwithstanding its power, the dream was ultimately unrealizable. Indeed, the machine by which the dream was to be accomplished could be taken apart, misused and presented in the guise of its nightmarish double, or occasionally as something wonderfully unlike it.

“Fast, Cheap & Easy: the Copy Art Revolution,” features works from over 100 artists on all four floors at CEPA’s Market Arcade location. The exhibit runs through December 15.

Shane Meyer is Programming Director at Big Orbit Project Space, a CEPA affiliate.