Book Launch: American Chartres: Buffalo’s Waterfront Grain Elevators

In 2009, Bruce Jackson unwittingly began a project, the seeds of which had been sowed three years earlier. That year, 2006, Jackson—a SUNY Distinguished Professor with a long history of local activism—wrote about and photographed the demolition of the H-O Oats grain elevator to make way for the Seneca Buffalo Creek casino.

His focus then was on the needless demolition of an iconic structure to make way for a business he and many others opposed on principles that had little do to with preservationism: a gambling operation in the city’s not-yet-burgeoning downtown. “I did not realize then that I would spend so much time engaged with these structures,” Jackson says. “I could not have imagined, because I did not know or really see them them. For all the time I had driven by them—decades, really, I’ve lived here for almost 50 years—I had hardly noticed or recognized them.

“Surprising, then, that I would spend so much time over the next several years looking at these incredible structures.”

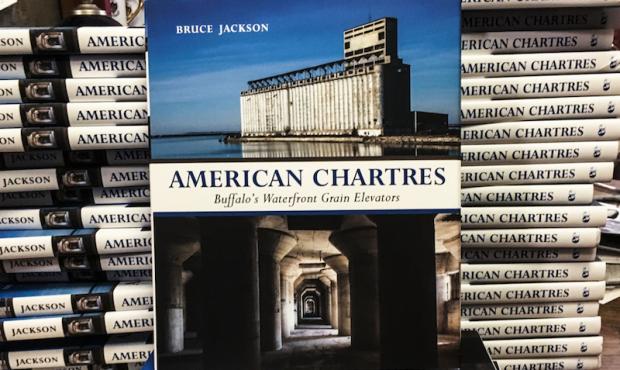

Jackson’s new book of photographs, American Chartres: Buffalo’s Waterfront Grain Elevators—the name taken from an exclamation by the poet Dominique Fourcade, upon his tour of Buffalo’s waterfronts, and reiterated in a show of Jackson’s photos at the UB Anderson Gallery three years ago—will be launched this week with a party at Silo City, Friday, November 4, 5-8pm. It is an astonishingly beautiful document of form: Jackson, an accomplished social historian, comes to the structures with an eye for their geometry, their scale, their imposition on the waterfront and landscape over which they tower. They are indeed, Jackson says, cathedrals to American enterprise—and particularly to Buffalo’s must lucrative and determining enterprise, which was transportation of goods and people (but especially goods) between the Midwest and the port of New York City, first enabled by the Erie Canal and later by railroads, which were in time overcome by highways and overland trucks and the Saint Lawrence Seaway, as well as by transportation routes to ports on the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

Modern grain elevators were invented in Buffalo of necessity (the first one opening in 1843, designed and built by merchant Joseph Dart and engineer Robert Dunbar) to store the agricultural products of the Midwest. “Grain goes in the top and out the bottom,” Jackson points out, so that the oldest grain is shipped first, reducing spoilage. That’s all they do. Simple.

“They are the biggest single-purpose machines I know of, except perhaps an aircraft carrier,” he says. “For that alone, they are remarkable.”

The book comprises 167 photographs of 15 elevators, culled from around 9,000 Jackson made over six years. (The most recent image is from April 2015. “I tend to work very slowly,” Jackson says.) There are exterior shots taken from the ground, from on high, and from the water. There are interior shots of many elevators, thanks to the cooperation of their owners: Sam Savarino, Carl Paladino, and, most notably, Rick Smith of Rigidized Metals, who owns the Silo City complex where the book launch takes place.

Smith gave Jackson the run of the place, and Silo City’s onsite caretaker, Jim Watkins, provided Jackson guidance and information about the structures, their history, and their current uses. Jackson was often accompanied as well by architect and fellow UB professor Kerry Traynor.

Smith gave Jackson the run of the place, and Silo City’s onsite caretaker, Jim Watkins, provided Jackson guidance and information about the structures, their history, and their current uses. Jackson was often accompanied as well by architect and fellow UB professor Kerry Traynor.

Smith bought his collection of elevators and attendant structures relatively cheaply, though at first all he wanted was land to build a road for trucks exiting Rigidized, which is congruent with the silos. He and some partners considered repurposing the silos for an ethanol plant, but that venture failed to get off the ground. In recent years, Smith and Watkins have made the silos available to artists and actors, filmmakers and musicians, who have breathed life into the site and drawn international attention.

“That wasn’t really happening yet when I started going there, at Rick’s invitation,” Jackson says. “With a few exceptions, Kerry and I were the only humans to be found when we visited. And Jim Watkins. She and Kerry would look out for me, make sure I didn’t put my foot down someplace that couldn’t hold me. They are remarkably durable structures, but there are some pretty dangerous spots, too. If you fall, you fall a long way, on to something very hard.”

There were a few encounters, about which Jackson writes in the book: another photographer, deer and water fowl, a suspicious police officer with pistol drawn. He often brought his dog Emily for company and protection. In March 2012, he brought the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, in town to perform Babi Yar with Buffalo Philharmonic. In the r esonant main room of Perot, Yevtushenko proclaimed Russian verses in his deep, echoing voice. “None of us understood a word,” Jackson says, “but it sounded just marvelous.”

Jackson’s photographs show the hulking structures in all seasons, in different lights. Rarely, he says, did he consider anything about the images they presented than the images itself: how the lines intersect, how the light falls, the colors, the relationship between water and sky and building. “Of course I could not help but be informed by what I already knew and what I was learning about these places, and the people who worked in them,” Jackson says, citing in particular a 2007 book edited by fellow UB professor Lynda Schneekloth, Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis: Buffalo Grain Elevators, to which American Chartres makes a fine companion. For the most part, however, he considered them as objects foremost, and looked past the evidence and detritus of the labor and laborers who worked them.

Not always. He describes one elevator whose columns are decorated with caricatures, clearly drawn by one person, presumably of fellow employees and bosses. “Imagine this guy taking the time to draw these things during his workday,” he says. “It’s wonderful to think of it.”

In the years since they were abandoned, of course, the silos have been canvasses for graffiti writers and playgrounds for teenagers. And in the last several years at Silo City, graffiti has been supplanted by murals and other artwork, some permanent (if there is such a thing, a question to which the silos offer contradicting answers) and some temporary. Jackson’s book is a beautiful document that freezes these magnificent structures—whose historic and cultural significance continue to resonate—in there current between-state: between vitality, decline, and perhaps revitalization.

It’s a terrific book—and Friday’s launch party offers a fine opportunity to pick up a copy and have a look around at the objects that inspired it.