Truth and Stories: Pawn Sacrifice, The Stanford Prison Experiment

I suppose that there are happy, well adjusted, even-tempered geniuses out there: It’s a big world. But no one ever makes movies about them.

Bobby Fischer was, by any understanding of the word, a genius at the game of chess. He was the youngest ever American grandmaster of the game, and the only American world champion of the 20th century. And he was none of the things listed above. Ergo, a movie.

If you think chess isn’t a very interesting subject for a movie, don’t take my word for it: Go right to your computer and look up the trailer for Pawn Sacrifice. It’s filled with rapid cutting, probing camerawork, intense acting, and snappy dialogue. (My favorite line, from a discussion of Fischer’s instability: “Bobby won’t crack—he’ll explode.”)

The movie focuses on the event that made Fischer internationally famous, his 1972 world championship match against Russian champion Boris Spassky. It was the height of the Cold War, and the match was pitched as “World War III on a chessboard,” a chance for the US to beat Russia in a competition they had dominated for years. (You may recall the recent documentary Red Army, about the USSR’s similar dominance in world hockey in the same era.)

But as we see from Fischer’s back story, he has more at stake than political piffle. The son of a single Jewish mother who was monitored by the FBI for communist sympathies, he despises “commies” and Jews with equal fervor. And he hates that the Russians have, in his opinion, conspired to keep him from taking the title.

Fischer is played by Tobey Maguire, who also produced the film. It’s a juicy part that lets him pull out every tool in the actor’s repertoire. He gets to rage, he gets to sulk, he gets to cower in fear, he gets to doubt his mother’s love. Forget about wimpy Peter Parker: Imagine James Cagney with a dash of Anthony Perkins. Spassky is played by the eminently watchable Liev Schreiber; for most of the film he doesn’t get to do much but glower and smirk condescendingly, though if that’s what a part calls for, you could hardly ask for better casting.

The film is directed by Edward Zwick in matching style. He doesn’t miss a trick to ratchet up the tension, especially in the scenes where most of us are likely to have no idea what’s really happening, as Fischer faces his nemesis Boris Spassky over a chessboard. There wasn’t a moment of the movie that I didn’t enjoy enormously.

But then the movie ended, and I had to think about all the stuff that wasn’t there. Movies about real people inevitably do a lot of shaping to turn their lives into something that has a cinematic structure, so you come to expect that a lot will be excised and a lot elided. Fischer died in 2008, and there was a lifetime of craziness that followed the events here. But Pawn Sacrifice pushes too far to try to make the argument implied in this title, that Fischer was used by the United States government as a propaganda tool, denying him the psychiatric care he seems to have needed. The script takes a real character, lawyer Paul Marshall (played by another dependably watchable actor, Michael Stuhlbarg), who worked as Fischer’s handler and manager, and invests him with a lot of shadowy governmental or quasi-governmental connections. He’s always making behind-the-scenes arrangements that are never explained, and which I suspect were invented by the scriptwriters.

As so often happens in films that begin with the phrase “Based on a true story,” Pawn Sacrifice is a cunningly crafted entertainment that does a disservice to the people whose stories it co-opts. It opens Friday at the Eastern Hills and North Park theaters.

* * *

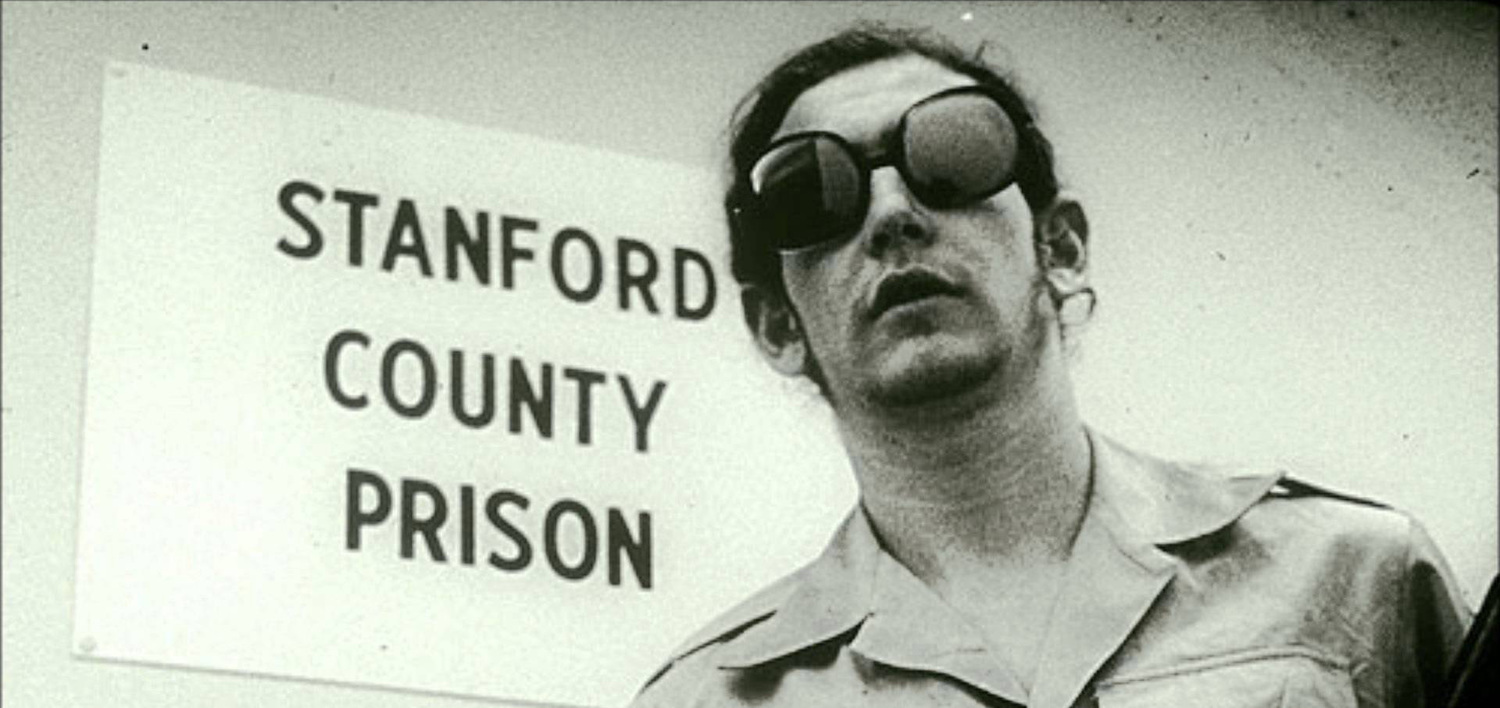

If you ever took a psychology class in college, there are two experiments you probably remember reading about: those conducted by Stanley Milgram in the early 1960s, in which he found that people could be pressed to administer deadly shocks to another person simply on the basis of the experimenter’s insistence; and that held at Stanford in 1971 by Dr. Philip Zimbardo, who set up a fake prison in the basement of a university building and populated it with 24 students, randomly assigned to be prisoners and guards.

The Stanford Prison Experiment recreates that study, whose results were far beyond anything Zimbardo and his collaborators expected. Not only did both groups of students fall deep into their roles—submissive prisoners, bullying guards—they did so after only a few days. The most fascinating parts of the film depict the experimenters themselves, who are equally quick to abuse the power they have given themselves over the lives of others. It plays this weekend at the Screening Room.