Bring Back the Broadway Auditorium

Bulldozing history to honor history may seem like a contradictory idea, but Mayor Byron Brown seems prepared to do exactly that. The Brown administration is discussing a plan to demolish the Broadway barns on the near East Side. That’s the building that has served as a truck garage and road salt storage facility for the city’s Department of Public Works for more than six decades.

Brown’s plan is to throw down the hulking old structure in order to clear land for unspecified “development” along the Michigan Street African-American Heritage Corridor. At first blush it’s an admirable concept. After all, in its current state the garage is a dilapidated shed of brick, corrugated metal, and broken skylight windows, and the exhaust from the sanitation trucks and snowplows it houses is not healthy for nearby residents. And who could object to any project meant to highlight the history of black Buffalo?

There’s one problem. Tearing down the Broadway barns would obliterate a significant piece of the history of black Buffalo—and Six Nations history as well, not to mention Buffalo’s civic history as a whole.

Because before the Broadway barns became a garage, it was the Broadway Auditorium, Buffalo’s premier indoor site of civic assembly from 1910 to 1940. There, on Broadway between Milnor and Nash, Joe Louis fought, Jay Silverheels played lacrosse, and many other great national and local athletes boxed, wrestled, ran, skated, cycled, bowled, and otherwise entertained generations of Buffalonians.

Nor was this once grand building simply a sports venue. It hosted dances and concerts—Enrico Caruso, Ella Fitzgerald, and Cab Calloway performed there—as well as circuses, masquerade balls, rallies, conventions, and conferences, including one where President Woodrow Wilson spoke. It was a National Guard armory from 1884 until 1907. Its legacy goes back even further, to 1858, when it was built, smaller and more castle-like, as an arsenal. A small part of that original arsenal still remains, making the cavernous shed one of Buffalo’s oldest extant civic structures. In a city littered with abandoned buildings, somehow the Broadway Auditorium has always proven useful.

And if the Broadway Auditorium is no longer suitable as a municipal truck garage in this, its fourth or fifth guise in more than 150 years of service, its sturdy construction and vast, airy interior give it the potential for further usefulness in a new guise. Even its 1910 façade is still intact behind the exterior brickwork.

Broadway Aud postcard (Courtesy of the Campaign for Greater Buffalo History, Architecture, and Culture)

But that potential may go unrealized. In recent years the mayor and members of the Common Council have quietly pushed for demolition of the building, arguing that it obstructs the Nash House Museum, the Michigan Street Baptist Church, the Langston Hughes Institute, and the Colored Musicians Club—the centerpieces of the city’s nascent African-American Heritage Corridor.

“You go to the Nash House and you see this monolith there that just takes over a third of the block,” Common Councilman David Franczyk told the Buffalo News in 2011. “It’s out of proportion. It totally takes away from that experience. If you’re a tourist coming in, you see this building with trucks going in there.”

Exactly how chimerical may be the notion of tourists arriving in great numbers to visit the Nash House is open to debate. But Brown seemed to argue for the idea in February when he told state lawmakers in Albany he would seek funding for a new facility to house the city’s entire public works department, including trucks and plows. He explained to the News that the facility would be located in another, “more industrialized” part of Buffalo, allowing for the demolition of the Broadway Auditorium.

Estimates for the cost of a new public works facility begin at $40 million. Meanwhile, yet another vacant lot would be created where the Broadway Auditorium stands today. With nothing having materialized on the long-vacant lots nearby, Brown’s vision of development for the Broadway barns site falls somewhere between optimistic and dubious.

Last week, some city officials said they favored reuse of the Broadway Auditorium rather than its demolition, in light of its history and potential future utility. Even Franczyk walked back his 2011 remarks.

But Brown did not respond to repeated requests for comment, nor did Common Council President Darius Pridgen, in whose Ellicott District the building stands.

If a clash over the Broadway Auditorium’s future is shaping up, it would pit an unusual set of opponents. On the demolitionist side would be Brown and Pridgen, two of the city’s top black politicians, and groups seeking to highlight Buffalo’s black history.

Yet the preservationist side would also include groups seeking to highlight Buffalo’s black history, as well as Native American and civic history—a recipe for a heated debate that goes beyond the usual argument over the future of an old building.

Any possible dustup could have its first round on Tuesday afternoon, April 21. That’s when the Michigan Street African American Heritage Corridor Commission holds its next public meeting, where the subject of the Broadway Auditorium is sure to come up.

The sweet science

Even if Joe Louis had not fought at the old Broadway Auditorium, its boxing pedigree alone makes it a place of note. The heavyweight champions Jack Dempsey, Primo Carnera, and James J. Braddock fought there, as did Benny Leonard, the great Jewish lightweight champion. Harry Greb, rated the best middleweight of all time by boxing historians, fought there 16 times between 1916 and 1926.

And of course, Jimmy Slattery, the hard-drinking son of a First Ward firefighter who briefly reigned as light heavyweight champion, ran up an incredible 71-1 record in bouts at the Broadway Auditorium, cheered on by his adoring fans.

Broadway Auditorium interior, early 20C (Courtesy of E.H. Butler Library)

But Louis’s moment at the Broadway Auditorium, on the night of January 11, 1937, is of exceptional significance, not to mention an event that makes Brown’s push to eradicate the building in the name of black history seem especially contradictory.

“One of the greatest fight crowds ever to witness either a title or non-title bout in Western New York is expected to jam the Broadway Auditorium tonight to see Joe Louis, the fanciful Brown Bomber from Detroit,” the Courier-Express wrote that morning, capturing the air of expectation surrounding the match.

The previous June, Louis had been knocked out at Yankee Stadium by Max Schmeling, the heavyweight from Nazi Germany—a stunning defeat for Americans, and especially for black Americans. “No one else in the United States has ever had such an effect on Negro emotions—or on mine,” Langston Hughes wrote of Louis, and went on to describe the reaction in Harlem to Louis’s defeat: “After the fight, which I attended, I walked down Seventh Avenue and saw grown men weeping like children, and women sitting on the curbs with their heads in their hands.”

Louis, out to avenge that defeat, scheduled a series of bouts intended to culminate in a rematch with Schmeling. One of them was the Broadway Auditorium fight, against Stanley Ketchel, a lightly regarded former Louis sparring partner called “the blond Jerseyite” by the Associated Press.

The auditorium was at capacity, 7,328, when ticket sales were stopped due to fears of overcrowding. Louis-Ketchel was the last of a seven-bout card; when Louis appeared the fans greeted him with “a tremendous cheer,” according to the AP. The fight lasted only to the 31.5-second mark of the second round, when Louis knocked Ketchel out with a lightning left. But the crowd was still thrilled to see the boxer the Courier called “the amber assassin” apply “the famous Louis bombing process.”

His Broadway steppingstone behind him, Louis stayed overnight at the Vendome Hotel, a famed black nightclub nearby on Clinton Street, and departed the next morning for an exhibition fight in Minneapolis. He went on to defeat Braddock, the heavyweight champion, that June, and Schmeling in 1938, a victory viewed as sweet vengeance not just for the Brown Bomber but for all black Americans.

Louis was one of several black fighters to box at the Broadway Auditorium in the pre-Civil Rights era, including such legendary pugilists as Joe Jeannette, Battling Siki, John Henry Lewis, and Henry Armstrong.

“All the great black fighters fought at the Auditorium,” the Buffalo boxing historian Bob Caico wrote in an email he said he sent to the mayor and some council members in 2012. “Many local black fighters fought there as headliners when many were not allowed to fight in other parts of the country.”

Caico—now president of the Buffalo Veteran Boxers Association, the organization better known as Ring 44—concluded that email with a plea: “I know the building is in rough shape now but we believe some sort of recognition should be given to what the Auditorium was for the community. If you need any information please do not hesitate to contact us.”

Caico said last week he received no response from the mayor or other politicians.

The creator’s game

However significant a role in Buffalo’s African-American history the Broadway Auditorium played, it may have had a bigger role in Native American history, as one of the founding venues of box lacrosse in the early 1930s.

Traditional lacrosse was moved indoors by the owners of the Montreal Forum and Maple Leaf Gardens, as a way to fill open dates in those arenas during the Great Depression. In 1932 and 1933 Buffalo had a team in the first indoor pro league, the Buffalo Bowmans, who ran the Broadway Auditorium floor against the Toronto Maple Leafs, Toronto Tecumsehs, and Cornwall Colts. They also played against teams from Pittsburgh and Chicago.

The Buffalo Bowmans’ big stars were the Smiths, four Mohawk brothers and cousins from the Six Nations lands at Grand River, near Brantford, Ontario. They’d played together as part of an unbeatable team in Atlantic City.

Perhaps the best of the Smith brothers, Harry, lived for a while in Buffalo, where he also became a local Golden Gloves champion. He was handsome, and so fast he earned the nickname Silverheels. He went to Los Angeles, got into films, and emerged as a star in the 1940s, billed as Jay Silverheels. Under that name he appeared in more than 80 films, became famous playing Tonto in The Lone Ranger television series, and founded the Indian Actors Workshop. He spoke out against Hollywood stereotyping of Indians and pushed white directors to cast native actors in native roles.

But at the Broadway Auditorium in the 1930s, Smith was only part of a huge wave of box lacrosse, from municipal leagues to the pros, often featuring Iroquois players from Buffalo, Western and Central New York, and Southern Ontario. They reveled in their ethnicity, and the local papers gleefully played it up as well.

“Son of Mohawk Chief Shines as Bowmans Bow to Toronto 7,” read the headline to Cy Kritzer’s Buffalo Evening News article on the first professional lacrosse game at the Broadway Auditorium. In 1934 a Pittsburgh paper referred to the Bowmans as the Buffalo Indians and gave their starting lineup as “Little Elk, Deerfoot, Chief Martin, Tecumseh, Long Boat and Running Deer.” In reality, the starting lineup of seven players featured Harry Smith, two other Smiths, and, in goal, Judy “Punch” Garlow, another Mohawk star whose voluminous scrapbooks can be viewed online today at Wamps Bible of Lacrosse, bringing the Broadway Auditorium’s forgotten past as a locus of Six Nations culture vividly back to life.

Still, the history of Native American lacrosse achievement in Buffalo and the Broadway Auditorium is largely forgotten today, even as the Bandits draw crowds of 15,000 to the First Niagara Center. Some say the dominant culture’s silence on such matters is no coincidence.

“I think it’s almost intentional, because they don’t want Native people to be acknowledged,” said Paula Whitlow, director of the main Six Nations educational institution in Brantford, the Woodland Cultural Centre. “They think if everyone forgets about them, then we’re a forgotten people. And this has been occurring for 300, 400 years—it’s not anything new.”

Whitlow said she supports recognition of the legacy of Six Nations lacrosse in Buffalo and at the Broadway Auditorium specifically.

Community showcase

Almost every night during its 30-year heyday in the pre-television era, the Broadway Auditorium was alive and brimming with civic activity: basketball, jitterbug contests, wrestling, bowling, dog shows.

Buffalo Orpheus, the high society group that supported the Buffalo Symphony Orchestra, held its annual pre-Lenten masquerade carnival ball there, champagne flowing and colored lights flashing. In January 1931 the Buffalo Majors of the American Hockey Association played on a newly installed ice surface at the Broadway Auditorium, the first pro hockey game within the city limits. (Only six games were played there, but since the building dates to the 19th century, it may be the oldest in the world to have hosted a hockey game.)

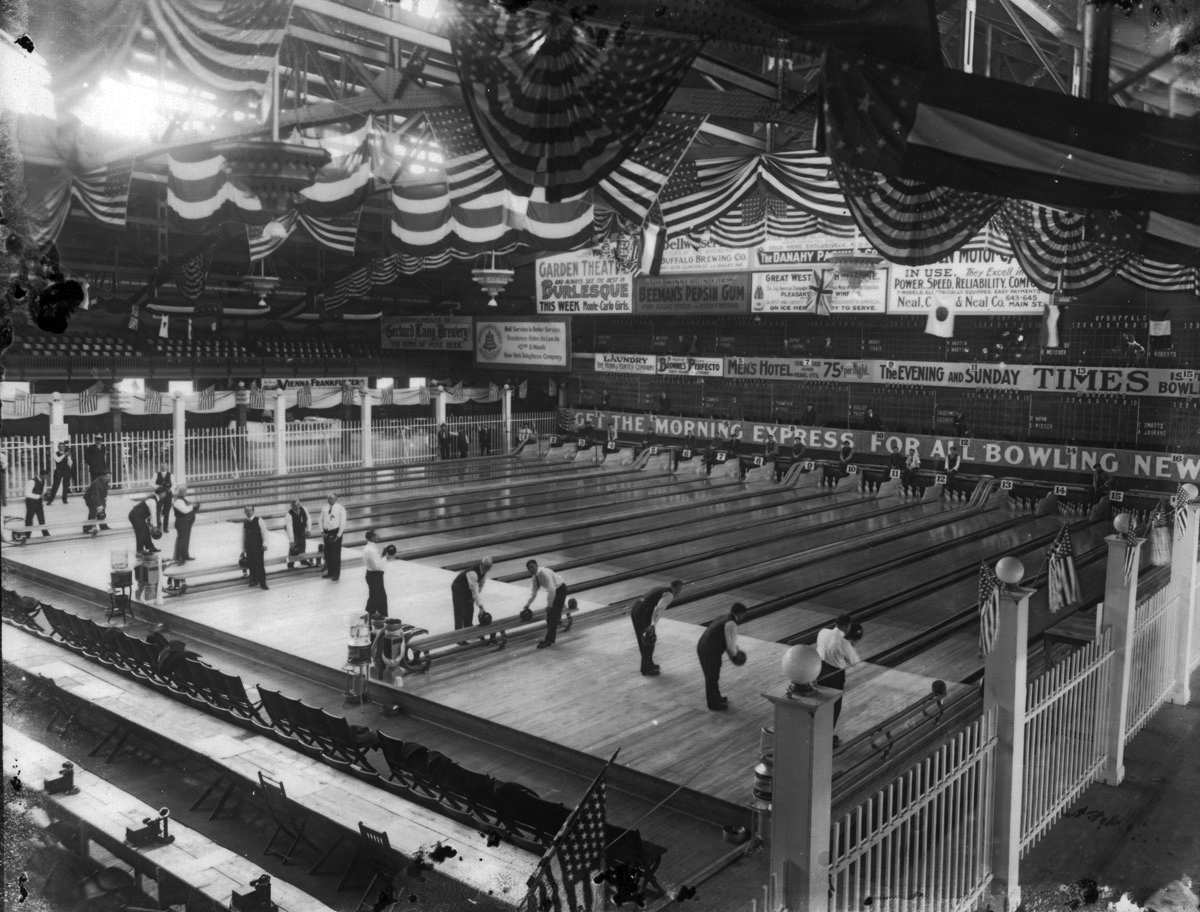

Broadway Auditorium — Bowling, n.d. (Courtesy of the Buffalo History Museum)

And six-day bicycle races thrilled crowds. “Cecil (Speed’s My Business) Yates and Heinz Vogel stormed into undisputed first place in the six-day bike race at Broadway Auditorium shortly after 1 o’clock this morning,” the Courier wrote on March 9, 1940, “climaxing a riotous evening of unprecedented jamming that had another banner throng fairly tearing the roof off of the venerable structure.”

Within a few months all events had decamped the venerable structure for downtown and the newly built Memorial Auditorium. It reverted to Army use during World War II and by 1952 found new purpose as the garage for the city’s streets division. Today, Memorial Auditorium, lamentably, is gone, yet the old Broadway Auditorium still stands.

But for how long?

What’s next

The Broadway barns may be somewhat dilapidated, but the building remains structurally sound, according to Steven Stepniak, the commissioner of the Department of Public Works, Parks, and Streets. “It needs a new roof and some other things,” Stepniak said last week, but added it has several years of useful life left—a good thing, he noted, because any new public works facility is still some time off in the future.

While demolition of the building is not imminent, its future is nevertheless precarious.

“It’s definitely not something you want in the middle of a tourist attraction,” said Karen Stanley Fleming, chairperson of the Michigan Street African American Heritage Corridor Commission, the nonprofit agency funded by the New York State Legislature to guide the creation and growth of the neighborhood as a cultural tourism destination.

“We have called for removing city services from that site and a feasibility study of what is architecturally significant and should be saved and what could be torn down,” Fleming said of the Broadway barns.

Broadway Auditorium — Exterior, 1941 (Courtesy of the Buffalo History Museum)

The Heritage Corridor commission can only make recommendations to the city on what to do with its building. The commission takes no official stance on the Broadway barns’ future, but Fleming said the commission could support some kind of repurposing.

“The commission’s management plan recognizes that the property has a very high significance both historically and architecturally, and that includes significance in terms of black history,” Fleming said. She said that whatever happens to the building, “we’d hope it’ll be something in keeping with the corridor’s vision to be a world-class tourist destination in an attractive neighborhood where residents can live, work and play.”

What might such a repurposing look like? In New York City, old armory buildings of similar ages and dimensions as the Broadway barns are in use as active public gathering places.

The Park Avenue Armory on the East Side of Manhattan is a venue for the arts. The Fort Washington Avenue Armory in Upper Manhattan, converted to an indoor track and field facility in 1997, is now considered one of the country’s premier field houses, constantly busy with high school, college and adult runners on its six-lane track. The Kingsbridge Armory in the Bronx is being converted to an ice center, with multiple rinks for hockey, figure skating, and curling.

Buffalo may not need another ice center, but the idea of converting the Broadway Auditorium into a track and field facility is attractive to Greg Lavis, president of the Checkers Athletic Club, one of Buffalo’s biggest running clubs.

“We would love someplace like that,” Lavis said. “There’s really not any good place to run indoors. There are some gyms with indoor tracks, but nothing measured and usually just one or two lanes. I’d imagine the schools would like it, and some of the colleges.”

Corporate money funded the conversion of the Armory in Upper Manhattan. It is less likely such money would be available in Buffalo, unless some funding came from the $40 million Brown requested from the state for a new public works facility.

If somehow the Broadway Auditorium were remade into a field house for public school kids, college students, and adult athletes, it would be in constant use, creating a steady flow of people that would at least enliven a currently depopulated neighborhood and at most generate the establishment of businesses there. That would transform the Michigan Street corridor from a static place of small museums meant for occasional tourists into a vibrant daily destination for the citizens of Western New York.

Other reuses for the building have been discussed for the Broadway barns, like convertig it into an arts center. Carl Paladino said last week he thought it would make “an awesome music house of some sort, for smaller concerts or other entertainment events.”

Paladino is often at odds with African-American leaders, but occasionally he aligns with black interests, as he did last month in financing the restoration of the Broadway Theater by Western New York Minority Media Professionals. Paladino said he was not considering investing in the restoration of the nearby Broadway Auditorium if the city were to sell the building, but he wanted it preserved—a fate that eluded Memorial Auditorium, whose destruction he called “a big mistake” and “really stupid and shortsighted of our city fathers.”

“The thought of them knocking this down without making use of the infrastructure—how insane is it to knock something down that has all that value to it instead of putting it to another use?” Paladino said. “It’s as devoid of insight as anything I’ve seen.”

It’s perhaps telling that Stepniak, the city official most familiar with the Broadway barns, wants to see the building standing and repurposed after his snowplows and sanitation trucks leave.

“There’s historical significance to that building,” he said. “I love Buffalo’s history, and I believe this is part of it. Just because we don’t need the building doesn’t mean that building’s done with—it still has plenty of useful life left. It’s up to people to just get a game plan together with other folks and say what the best future use is for that facility.”

Awareness of the Broadway Auditorium’s history, and of its potential going forward, seems to change the minds of at least some demolitionists.

Four years ago Franczyk saw the building as a big, ugly monolith that ought to be torn down to clear space for the African-American Heritage corridor. Last week at the start of a phone conversation he amended those comments slightly, saying the original armory walls that date back to the 1850s should be left standing and affixed with some kind of historical plaque.

Then he was informed of the Broadway Auditorium’s history: Joe Louis, Ellis Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Jimmy Slattery, Woodrow Wilson, Jay Silverheels, Little Three basketball. “Okay,” he said, “but it still looms like an aging colossus that doesn’t have any architectural significance, and it’s pretty ugly.”

Then he was told of some of the ideas for repurposing the aging colossus, like retrofitting it into a public field house.

“You have something there—that’s not a bad idea,” Francyzk said. “Let someone make a proposal. I’d be willing to look at any reasonable proposal.”

Whether the most important demolitionist, Mayor Brown, is willing to listen to reasonable proposals for the future of the Broadway barns remains to be seen. Last week, he wasn’t saying.