From the Vaults: Vincent Gallo on Buffalo and Buffalo 66

Love it or hate it—no one in our area has a lukewarm opinion on Vincent Gallo’s Buffalo 66, even if you’ve never seen it. If that’s the case, you can (and should) remedy that by seeing it this Thursday night at the North Park Theater, where it premiered in 1998. And because the internet gives us so much room, why not repost the interview I did with Gallo lo those 17 years ago?

Sit to the end of Buffalo 66 and you can read it, last and largest on the list of those to whom Vincent Gallo proffers his thanks: “The beautiful city of Buffalo and the wonderful Buffalonians.”

It might sound sarcastic, especially taken out of context; god knows we’re suspicious of compliments, particularly when they come from expatriates who have gone on to success in The Big City. But Gallo doesn’t seem given to sarcasm, other than that of the most obvious sort: this is not a man who will risk not having his meaning clearly understood. Overstatement and hyperbole are more to his taste, and a large part of what makes him so amusing to listen to.

So when Vince Gallo claims that he truly loves the city he fled when he was 17, what can we say but, “Gabba gabba hey!”

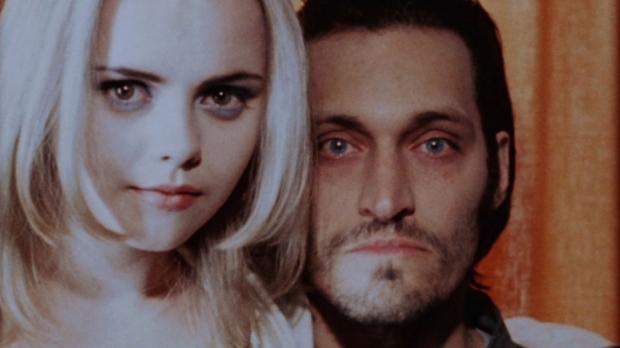

For the benefit of those few snowbirds who just got back to Buffalo this morning, Buffalo 66 was filmed entirely in the City of No Illusions last year by Gallo, a West Side native who left for Manhattan and a series of successful careers (musician, artist, actor) in 1978. While he says that it is not factually autobiographical, it seem to carry a lot of emotional biography in its alternately funny and touching story of a loser who kidnaps a young girl (Christina Ricci) to pose as the wife he has been writing to his parents about. (They don’t know that he’s just gotten out of prison.) After showing off to the family that never cared for him, he plans to seek revenge on the man who ruined his life, the placekicker who caused a certain local football team to lose the Super Bowl …

Certain to be the indie film of the year (even though 1998 is only half over), Buffalo 66 may be reminiscent in parts of the work of several other filmmakers, but in toto it’s as original a piece of filmmaking as I’ve seen in years. With a cast that also features Ben Gazzara, Anjelica Houston, Kevin Corrigan, Mickey Rourke and Rosanna Arquette, it’s also primed to capture more attention than most such non-studio movies.

The following interview was culled from two conversations with Gallo, one at Spot Coffee on Chippewa the day before the world premiere of Buffalo 66 at the North Park Theater, and one by phone a few days later from Manhattan, where his film was about to open to unanimously adoring reviews from respectable critics (as opposed to the ones whose names you usually see in ads):

Have you been back in Buffalo much since you left in 1978?

No, because I was not extremely connected with any group of friends, and certainly not with my family. I would come back every few years for a day or two.

Was there much about the city that had had changed from what you remembered when you were writing the script?

No. For instance, Chippewa St — when I was 10 years old I used to come here on my bicycle with my cousin Junior and we would buy platform shoes or hip, kinda soul shirts — they had really funky pimp-daddy styles. So when I came back here and went to get some bad ass clothes on Chippewa St. and saw what it is now, that was a surprise.

It’s a tragedy that downtown Buffalo has been so poorly maintained. The city is incredibly good looking, much more sophisticated than I think people who live here identify it as. There are very few cities in the country that have five Frank Lloyd Wright houses — one of them was torn down, and that’s a tragedy. The problem is that there is a midwestern sensibility here that’s very out of touch. It’s not as industrial and sophisticated as the city’s history. It’s kind of homogenized away from its turn of the century sensibility.

I was at the outdoor concert last night at Lafayette Square to see Squeeze, and I was looking at the crowd. I just don’t understand the clothing and those people who look so inactive, like they’ve just been walking around chugging beer for a long time. I forget that it has that kind of rhythm here — it’s not a very active city. People seem to at a very young age retire themselves physically, and I’m most surprised by that. And the clothing — Buffalo’s a very harsh, cold city, very tough winters, yet there’s never any really high quality warm clothing. Like if you go to Minneapolis, people were into down and thermal stuff, whereas here in the 70s we would wear those thin green K-Mart parkas and workman’s boots and thermal long johns and freeze our asses off all winter long.

How did you enjoy your return to Buffalo? Did your friends and family like the movie?

I think they did … It was pretty shocking, that whole thing. I got every friend from high school I would want to be proud of me, every relative, friends came down from New York for this big event in Buffalo. The whole thing was so beautiful, I‘m still overwhelmed, I’m so lucky to have been able to have had that catharsis with the city of Buffalo, because I really love it there.

I’m a real big fan of all of upstate New York, which is to say anyplace north of Manhattan. That’s why I was happy when George Pataki became governor, because the state had pandered economically to Manhattan for so long. When people outside of the state of New York think about the state, they can only identify New York City. It’s weird, because it’s such a beautiful state.

You were in a few bands in the 1970s before you left Buffalo for Manhattan. Do you remember the names of any of them?

I’d been in bands since I was 9 years old. The Blue Mood, the More, the Plastics, the Good, Zephyr, Brown 69. I played mostly bass guitar and sang sometimes. They were first all progressive and then punk bands.

After I went to New York in 1978, I was in a very, very famous band called Grey, with the artist Jean-Michel Basquiet. And when I say famous then, it doesn’t mean we had a hit on MTV or did a world tour or anything like that. I meant that in the New York City underground, which was very potent and exciting, we were a very significant band, very industrial, minimal, noise band. After that I was in a band called Bohack, which released an album. And right after that I started composing music for films. I’m in a band now with the actor Lukas Haas called Bunny. We’re doing an album for Sony, similar music to what I’ve always been doing. But collaborating with Lukas, it’s evolved to the point where its the best thing I’ve ever done.

Does it bother you that most people at this time recognize you less from you movies than from the series of Calvin Klein ads you made with photographer Richard Avedon?

I’m not offended by that because my relationship with Avedon was certainly the most exciting work relationship I’ve had. I’d always admired him. My mother and father were hairdressers — I grew up in a house with a beauty salon in it. My parents had no books — no novels, no Bible, no kid’s books, no record collection, no radio, nothing like that. But in my mother’s beauty shop, there was Esquire and Vogue and fashion magazines. So my first relationship with visual art came from fashion magazines — and with the written word, because there were interesting articles in those magazines. Avedon did brilliant work during that time, and I was madly in love with Susan Blakely and Veruska and Lauren Hutton and other models. So for me to work in that environment, in commercial fashion photography was exciting. But I’m not attractive, I’m not a model — if I could be a model, I would be a model, believe me. But I’m not.

How long ago did you write Buffalo 66?

I wrote the first version in 1989. It was virtually identical to this script, but it was before Super Bowl 25. Instead of trying to win a big football bet, the main character was trying to win this big part in a movie and he fucked up. Shortly after I was in Arizona Dream and I kind of rewrote my part and made him a wanna-be movie star like this character. Right as I did that, Buffalo loses the Super Bowl. So having using up that character and seeing this tremendous melodrama made me rethink my original script. So I rewrote that part of the script with a girl who’s credited as my writing partner but who really was my typist for a couple of weeks, and I had to give her that credit because I didn’t get her to sign anything first. So be careful out there, kids.

Did you have to get permission from the Buffalo Bills for the film?

The Buffalo Bills were not cooperative or interested in helping me in any way whatsoever with the film, nor was the NFL. I’m a little bitter and resentful about both those experiences. The witch — this woman, this witch woman who worked for the NFL was really unpleasant.

So I didn’t even use the Bills logo. Aside from fans wearing something, I was not allowed to feature the Buffalo Bills as a football team. I had to reinvent the logo — it’s just a big “B” on a helmet. And the team in the movie is never called the “Buffalo Bills” — they’re just called “Buffalo” or “the Bills.” There’s a hundred teams called “Buffalo.” And there’s also been a lot of “Bills” — there are high school teams with that name. So as long as you don’t put “Buffalo” and “Bills” together, I’m not infringing on their copyright.

I assume the same was true of Scott Norwood?

Yeah. The character in the film is “Scott Wood.” He had no sense of humor about himself or about the events. I offered Scott a chance — I was willing to make his character have become whatever he wanted his character to have become. But he still wasn’t interested in participating in any way with the movie.

What did the movie cost?

Slightly under $2 million — below the line was about $1.2, then there was about $600,000 for salaries and such above the line.

How did you raise that?

Lionsgate [the film’s distributor] agreed that if I got certain cast members they would greenlight the financing. But with companies like that, all they actually do is agree to co-sign for a loan. You pay all the loan fees, the charges and the interest, and you also pay for the bond company to guarantee the loan. Companies like that are figureheads, just bean counters, they’re just doing business. However, one of the people from Lionsgate, Michael Paseornek, when I was in situations with bean counters that could have gotten ugly, he rose up and became an ally of mine. I’m very proud of my relationship with Lionsgate because of Michael.

According to an interview with you in Filmmaker, you insisted on using a reversal stock, an archaic kind of film that almost couldn’t be developed. What was special about that film?

Unlike regular film, when you develop reversal stock it doesn’t come out as a negative — you can hold it right up to the light and see what the image is, only it’s transparent. It was developed years ago for news photography, so that you could film something and show it right away without making a print. But it’s never used in 35mm cinema because it’s virtually impossible to make a negative, which you need in order to make multiple prints. It’s very hard to light — I had to use tons of light to make the film work. And you can’t really color correct it once you’ve processed it. Negative film is so easy, it’s such a homogenized kind of film stock, you can shoot everything and then fix it later on. With reversal stock, you have to light precisely, you have to art direct your colors precisely, because there’s not much you can do with the film afterwards.

But the result is the best color saturation, the best contrast of any film I’ve ever seen in my life. It doesn’t look lush and high budget, it just looks like a modern classic. It looks like it was made always, like it just was always there. It fit the sensibility of my memories of the city. The first film I saw, which was a football documentary, was shot on reversal film. So it has a feeling of like watching football footage from the 1960s — not dated, just classic.

A lot of reviewers are comparing Buffalo 66 with the films of John Cassavetes. Was there any improvisation in the film?

I have no fascination with John Cassavetes, or with Jean-Luc Godard — they’re not two filmmakers that I like very much. Cassavetes is a good filmmaker, there’s no doubt about it, but he’s not inspirational to me personally. I did not cast Ben Gazzara [one of Cassavetes’ stock players] because I saw him in a John Cassavetes film, but because I saw him in a film with Robby Benson, The Death of Richie. Ben Gazzara was not allowed to improvise one word in the film. He really wasn’t interested in doing that anyway. And Christina [Ricci] can’t improvise anyway. I’ll show you the original screenplay, and it’s exactly what’s in the film.

Having directed your first film, after all the other things you’ve done in your life, do you now think of yourself as a “filmmaker”?

I’ve always thought of myself as a hustler, a control freak. Being in a movie has a certain amount of impact: it has social status, it has freedom, money, recognition, it gives me the ability to meet other people that I find interesting, it allows me to introduce myself to women easier, it gives me validation, it allows me to take revenge on my mother and father, who doubted me — I mean, that’s the real attraction. Once one does the work to get those things, then one can become interested in the actual work. But the thing that drives one is this whole other pathology. No other actors ever cop to that — they talk about whatever their banal concept of art is, but the driving force to me is that.

I’m really a controlling person. I don’t want somebody else to do the cinematography, I don’t want somebody else to do the poster - I did the poster. I don’t want somebody else to do the trailer - I did the trailer. I don’t want somebody else to do the casting - I did the casting. I don’t want somebody else to produce the movie - I produced the movie. I did the music, I designed the shoes, I controlled everything. Even if you look at the credits where it says costume person - I did the costumes. No one made any decisions on Buffalo 66, no one physically did anything unless it was my concept, my plan, my idea. That felt really good. Am I a filmmaker? No. A control freak and a hustler is what I really am.

Does making a movie give you too much to control?

No, it’s just that I’m 10 years older now than I was this time last year. It never ends. It never ends. Even after the film was printed and wrapped, there’s still the trailer, the posters, the previews, the invitations, I mean I want to control everything. After awhile one can be relentlessly seduced by the details of control, and that can be intoxicating, overwhelming and destructive on the body and the mind. So I’m a worn out hustler.

So are you going to do it again?

Absolutely, because I have no other other connection to life — I have no friends, no vacation activities, I don’t have serenity, all I have is chaos and compulsion. I can be productive in that way. And I’m comfortable sacrificing those other things, because I know now that in 50 years I can look at this and I won’t be cringing like I will about almost everything else I’ve ever had to collaborate on.

Aside from the New Directors/New Films series at the Museum of Modern Art in April, Buffalo 66 was shown previously only at the Sundance Film Festival., where the selection committee chose it as one of the films to be in official competition. How was it received?

I didn’t want to go to Sundance, it’s a bullshit festival. The whole concept of a film festival doesn’t interest me anyway, it has nothing to do with the evolution of culture, it has to do with special interest groups acting out their little power plays. I only went to Sundance because Lionsgate, secretly behind my back and against my wishes, submitted the film. And when it got accepted in competition they were so excited that Michael Paseornek begged me to let it go and to go myself and support the film. So I did that out of gratitude to Lionsgate.

Every year Sundance has the biggest group of assholes as judges. There’s always one or two interesting people, but in general the cast of clowns making selections at that festival is embarrassing. Who gives a fuck about Alfre Woodard? What the fuck does she know about film? Paul Schrader [who was one of the judges] is there with a film he’s directed that he’s desperately trying to sell but no one’s buying. So he immediately has a built-in resentment against anyone who’s made a film better than his movie that has a deal already. Then after the screening of Buffalo 66 he stays and listens to my Q&A, which he’s not supposed to do, and develops a resentment against me personally because he doesn’t like my cocky bravado. At Sundance all five judges have to unanimously agree on the prizes. So if you have one judge who doesn’t like you personally, there’s no way your film can win any prizes. So that’s what happened. Paul Schrader is a petty little vicious bitter queen, and I will punish him for the rest of his miserable life.

In some of your earlier interviews you would give the names of girls you knew in high school and ask them to contact you. Have you heard from any of them?

Yes I did. A lot of them came to the premiere. Somewhere in my mind I became incapable of loving or being loved without an incredible amount of fear and hate and discomfort. So the only memories I have of being excited by girls in a nice way — they were so cute, those Sweet Home girls that I went to school with, the way girls did their hair then, those halter tops, that long straight shiny hair. Girls don’t dress like that anymore. It’s not the youth — I’m not really interested in teenage girls. I just like that more simple, more natural, less Gap, mall-dressing that they started doing later on. Those girls that I liked in high school have stuck out in my mind — I’ve never gotten over those first attractions.

Are you afraid of ruining your memories by meeting people you haven’t seen for so many years?

No. I’m not interested in the expectation. I’m just interested in seeing people that I loved and still have affection for. I’m not hoping to see them and have a hot affair. I’m just very fond of that group of people in my life. Those are the only pure friendships that I remember in my life. I don’t have memories like that from New York City — they’re much different, more angst, more complex relationships that I had later in my life.

One of the people at the post-film party was Asia Argento, the award-winning Italian actress and daughter of director Dario Argento. [She’ll be making her English-language debut in B Monkey, the new film from Il Postino director Michael Radford, scheduled for release early in 1999.] How can we refer to her …. ?

She’s just a friend. We were goofing at the party that we were a couple, but we’ve never actually dated. I just met her a few weeks ago in Rome, and she became an instant very, very close friend. She told me on the phone today, because I teased my father and told him that we had secretly gotten married, she called me and said that I have to marry her now, otherwise I have to pay her for the performance. And she prefers getting married. But I’m not dating anybody. I haven’t had a girlfriend in several years. I guess somewhere there’d be somebody that would date me, but there hasn’t been anybody. I don’t really have the opportunity to have that kind of life. Men and women don’t come together in the way — they don’t have the kind of shared life that traditional couples did years ago. There isn’t anyone I feel would want to have a shared relationship like that with, where you have a relationship and you work together toward domestic and career goals

Is that even possible any more?

I don’t know. Couples don’t seem to interact like that. The only way that I could function in a relationship — I’m a very efficient person, so when I’ve had girlfriends, I want to be productive — let’s do this, I want to mail this, whatever. Because everybody has their own self-centered expectations in life, you don’t really feel like you’re working toward goals together. To me, a relationship should be something very productive. In the relationships of my parents’ generation, the men and women together were stronger than they were separately. The relationships I’ve had, I’ve felt stronger on my own. I felt like I was a caretaker, or I was in some sort of thing where I was not taking care of my responsibilities because I had to devote time to this relationship. I’m rigorous in that way — I would only want to have a relationship where we were working together.

I’m so severe about it now that I won’t even date. What’s the point of having this shared intimacy and privacy with someone only to do it again next year? I can’t bear it That’s why I stay alone — I just don’t want to repeat these little scenarios of romance over and over again, I’d rather just stay on my own. If I find somebody who I feel in a very fundamental way makes my life more productive, or allows us both to have more impact together, then I would get together. Unless the primary focus of a relationship is to have children — it sounds silly but that’s really the basic premise of coupling, and anything outside of that is slightly self-centered. So how long can one sustain that kind of relationship?

Do you ever see yourself having children?

I want them, but contemporary relationships are unattractive to me, I’m unattracted to the way people get together. I don’t want to be divorced and visit my children — that’s too inacceptable of a behavior, it’s a big risk.

What’s in the future for you?

In September I’m going to start making my next film, The Brown Bunny. I want to work with Christina Applegate, but I haven’t talked to her about it yet. I’d like to work with Charlotte Gainsbourg. There are three main girl parts — I’m not quite sure whom I’d like to have in the third part.

Will you be in it?

I’m not sure. I wrote the part in a way where I could play it, but I think maybe the world has seen enough of me.

Are you getting along with your family now?

I had a big catharsis in writing the script, and an even bigger one making the movie. I’ve grown fond of all the people in my family over the years. I haven’t forgotten really about the, uh, problematic relationships I had as a child, but I’ve certainly forgiven and moved on. I’m fairly resolved in those feelings — it’s not the main point of my basic nature anymore. My identity is not Vincent Gallo the resentful, angry, distrustful person that I was when I left home. I’ve just become this other asshole for other reasons.