Investigative Post: The Subsidy State

Governor Andrew Cuomo has sunk a lot of taxpayer money—$25 billion by his estimate—into recharging upstate’s moribund economy.

The governor has increased spending on subsidy programs to record levels, launched bold policy initiatives and crisscrossed upstate to announced projects he has frequently described as “game-changers.”

“Economic success is shared all across the state. It’s not just New York City that’s doing well, it’s the entire state,” the governor declared in his 2017 State of the State address in Syracuse.

That’s the rhetoric. The reality, as borne out by employment data, is decidedly different.

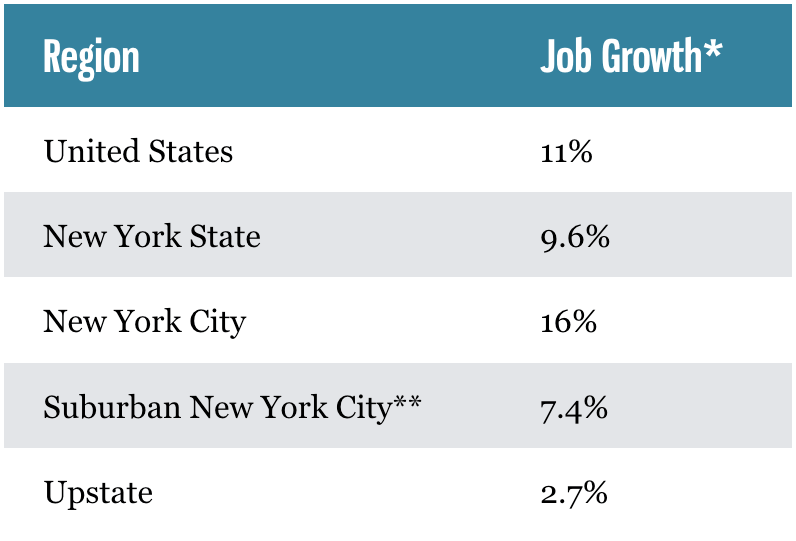

Employment upstate has grown by only 2.7 percent during Cuomo’s tenure—compared with 13.1 percent downstate and 11 percent nationally. Four of upstate’s 12 major metropolitan areas have actually lost jobs since Cuomo took office.

If it were a state, upstate’s job growth would rank fourth-worst in the nation, below, among others, Mississippi.

What’s more, 88 percent of the net jobs added upstate during the Cuomo years have been in low-wage sectors, led by restaurants and bars, employment data shows.

“The policies Cuomo says are focused on upstate, and he claims have improved upstate, were not the right policies and have not worked,” said E. J. McMahon, research director of the Empire Center for Public Policy, a fiscally conservative watchdog group.

Upstate’s Lagging Job Growth Under Cuomo

Employment gains a quarter the national average

* Increase between December 2010 and December 2016

** Includes Long Island and Westchester County and other northern suburbs.

Source: Fiscal Policy Institute analysis of non-agricultural employment based on data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and New York State Department of Labor.

Investigative Post, ProPublica, and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism teamed up to assess the state’s economic development efforts since Cuomo took office in 2011. They built a database that tracked some 16,000 subsidy deals involving 11 of the state’s largest economic development programs and locally controlled industrial development agencies.

Reporters also analyzed employment data, interviewed more than 45 officials and experts, and reviewed about a dozen reports and audits of subsidy programs conducted by the state comptroller and watchdog organizations.

The investigation found the state’s substantial investment in the Upstate economy has not yet generated many jobs upstate and that economic development programs suffer from a lack of transparency and objective analysis to determine their effectiveness.

The investigation also found the state does an inadequate job of vetting subsidy recipients to determine their history of compliance with federal and state regulators and that some companies have used their influence to tap into a multitude of subsidy programs and place executives on decision-making bodies that help determine how tax breaks and other forms of assistance are awarded.

The upstate economy has long suffered from a loss of both population and the manufacturing jobs that were once its bedrock. Experts note that economic development deals can only go so far in counteracting those forces. That hasn’t stopped elected officials from trying.

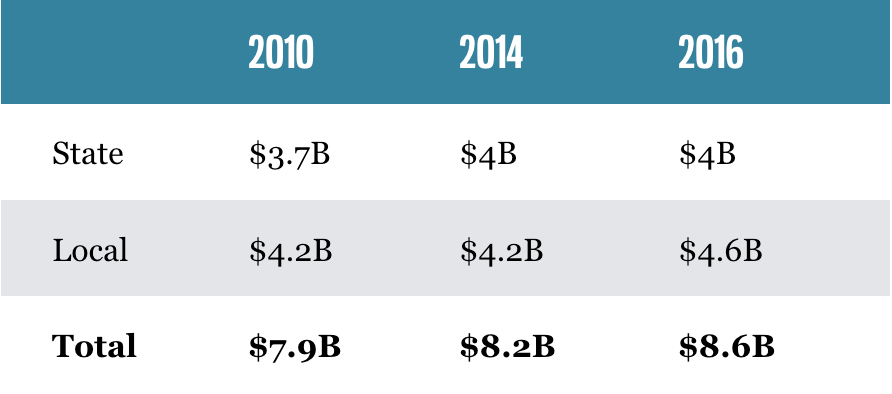

Both state and local economic development agencies have ramped up spending on subsidy programs since Cuomo took office. The total last fiscal year hit a record $8.6 billion, according to a calculation by the Citizens Budget Commission, a nonpartisan group that tracks state spending. And Cuomo has proposed a major boost for the coming fiscal year.

The governor has also introduced several major economic development programs that have failed spectacularly. His decision to empower former SUNY Polytechnic president Alain Kaloyeros to manage big-ticket projects built at taxpayer expense upstate has mired his administration in scandal, culminating in criminal charges against state officials and developers, and leaving many planned developments in limbo.

The Start-Up New York program, which Cuomo said would “supercharge” the upstate economy by creating tax-free zones for businesses locating near college campuses, has been widely criticized for meager job creation despite heavy state spending to promote it.

Furthermore, the investigation found that the state under Cuomo continues to pursue costly trophy projects. In fact, no state in the nation has helped finance more of these mega-deals.

Empire State Development Corporation, the state’s primary economic development agency, did not respond to requests for an interview with president and CEO Howard Zemsky or another senior official.

Growth in subsidies

While Cuomo has worked to slow the pace of state spending since taking office, the cost of state and local subsidy programs has grown.

The value of subsidies awarded at the state and local level grew from $7.9 billion for fiscal year 2011 to $8.6 billion for the most recent fiscal year that concluded last March.

The state’s share of that grew from $3.7 billion to $4 billion during that period. And Cuomo’s proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year calls for $644 million in additional economic development spending and $1.5 billion in future tax credits.

Increase in Assistance

Fiscal years ending March 31

Source: Citizens Budget Commission

“The governor has certainly ramped up economic development spending more than any governor in my 25-year history in Albany,” said Ron Deutsch, executive director of the Fiscal Policy Institute, a labor-backed think tank.

The sheer number of subsidy programs helps explain New York’s largesse.

There are property and sales tax abatements. Discounted power programs. Cash grants. State budget allocations to build and equip facilities for companies. And a growing number of state tax credits.

The Tax Reform and Fairness Commission empaneled by Cuomo reported that the number of state tax credit programs had grown from nine in 1994 to 50 in 2013, the year it issued its report.

Relatively few companies reap most of the benefits from these programs.

“A small number of taxpayers account for the vast majority of tax credits claimed,” the commission reported.

A report issued about the same time by ALIGN, an economic justice research and advocacy organization, found that only four percent of businesses across New York receive subsidies, and that many recipients are large, out-of-state corporations. ALIGN noted, for example, 14 separate subsidy deals for Target stores and warehouses. Walmart was another frequent recipient.

The state’s penchant for large, costly projects also contributes to New York’s high spending on subsidies.

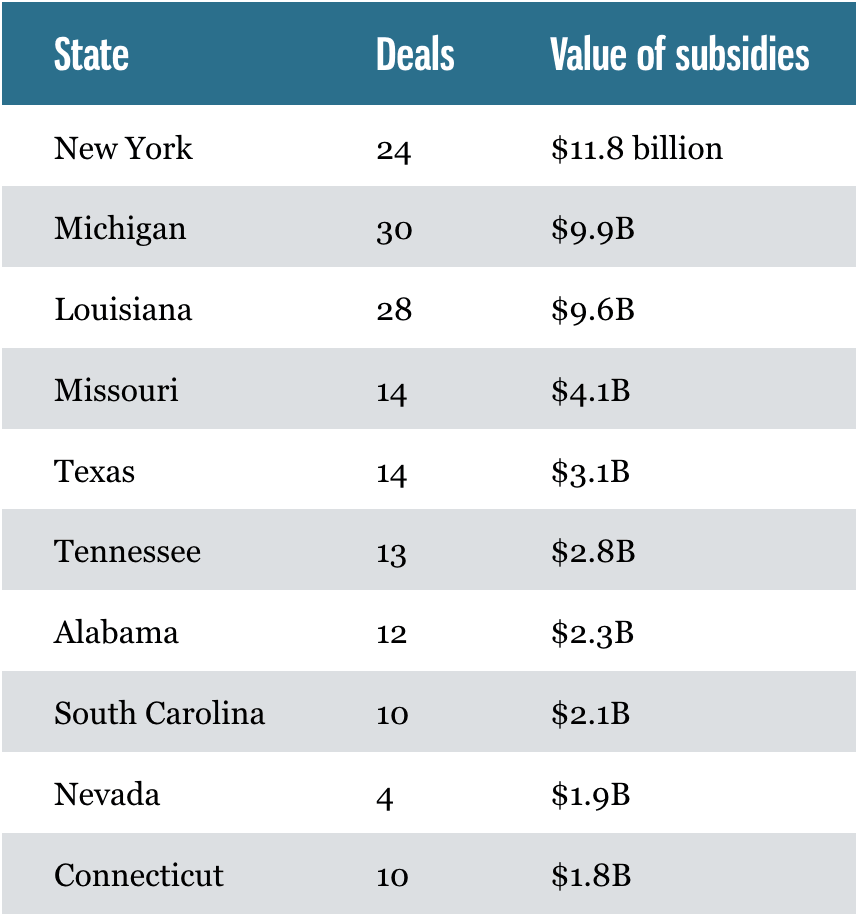

Megadeals

Projects involving subsidies of $50 million or more, 2000 to 2016

Source: Good Jobs First

New York committed $11.8 billion for 24 mega-deals, followed by Michigan ($9.9 billion) and Louisiana ($9.6 billion). No other state spent more than $4.1 billion.

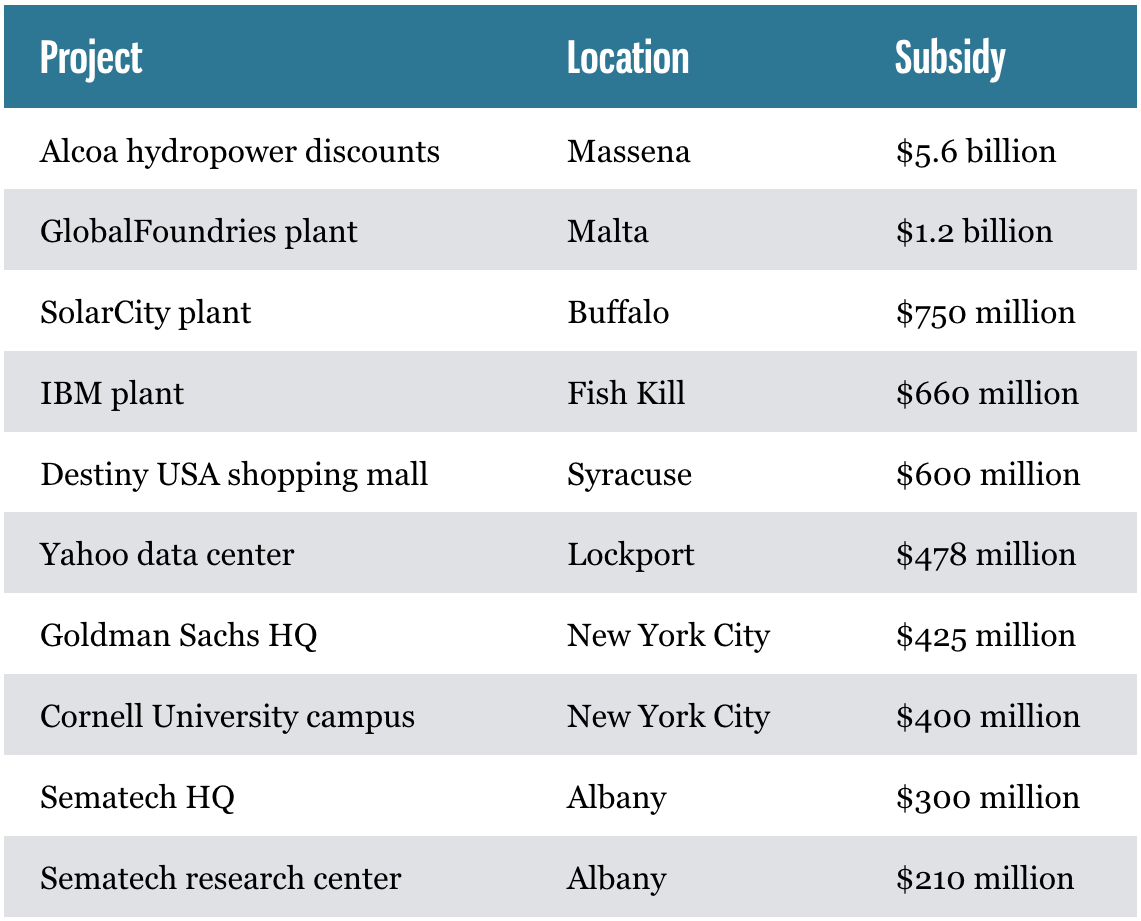

Only a half-dozen of New York’s mega-deals took place downstate. The six costliest deals benefited businesses located upstate and include Alcoa in Massena, GlobalFoundries near Albany, and SolarCity in Buffalo.

New York Megadeals

Ten largest deals since 2000

Source: Good Jobs First

LeRoy, of Good Jobs First, said mega-deals are “guaranteed losers for taxpayers.” The deals cost more than the government can ever hope to recoup through increased tax revenues, he said. As a result, the tax burden for public services is shifted to other taxpayers.

So why do mega-deals remain popular?

“They’re catnip for politicians,” LeRoy said.

Corruption mars major initiative

Cuomo’s boldest initiative attempted to turn the state’s traditional approach to economic development on its head by going even harder after mega-deals. Instead of extending subsidies to individual companies, Cuomo sought to replicate a model used by Kaloyeros to develop a nanotechnology sector in the Albany region.

It’s an unusual approach that involves taxpayers shouldering the cost of building and equipping advanced manufacturing facilities for a company recruited in exchange for job guarantees. In theory, these facilities would attract smaller firms and help establish an industry cluster.

“There is nothing like this in the United States or, so far, overseas,” Kaloyeros said at the time Cuomo was rolling out the Buffalo Billion program.

Empire State Development Corporation, the state’s leading economic development agency, was largely cut out of the process. Instead, the task of exporting the Albany model across Upstate was entrusted to Kaloyeros and two state-affiliated nonprofit corporations he controlled.

Problems soon ensued. The two development corporations, citing their nonprofit status, contended they were exempt from the state’s Open Meetings and Freedom of Information Law. They also maintained they were not required to follow state procurement policies.

The outcome: Developers who were major Cuomo campaign contributors were awarded lucrative contracts with hardly any competition. Last September, US Attorney Preet Bharara and State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman brought criminal charges of bribery and bid-rigging against Kaloyeros, top Cuomo aide Joseph Percoco, and developers in Buffalo, Syracuse and Albany.

Cuomo stripped Kaloyeros of his economic development portfolio after he was charged in September and he resigned a month later as president of the SUNY Polytechnic Institute. By then, the wheels had fallen off several other deals he had brokered across Upstate. Projects in Rochester, Utica, and Dunkirk have been delayed, scaled back or shelved altogether.

Meanwhile, a $15 million facility built outside Syracuse to serve as a filmmaking hub stands all but unused.

Start-Up New York, another of the governor’s marquee initiatives, has also floundered. State officials said the program, which allows companies to operate tax-free for 10 years by locating near university campuses, would lure businesses to upstate. The governor said it would “give New York an edge like never before” in attracting companies. But Start-Up New York created just 408 jobs in its first two years of operation, despite the state spending more than $53 million dollars to advertise it.

In this year’s budget, the governor proposes rebranding the program, reducing the number of jobs companies must promise to create, and revising the eligibility criteria to focus more on genuine start-ups. State officials maintain the program will create around 4,000 new jobs over the next few years.

A regional approach

Thirty thousand dollars for the installation of signs along the Niagara Wine Trail; $7 million for a high-tech incubator at Binghamton University; $35,000 to study the dairy goat industry in the Capital Region.

That’s just a sample of the hundreds of projects funded by one of Cuomo’s signature economic development initiatives, a system of 10 regional councils that develop plans based on regional strengths and compete for state funding—more than $4 billion so far.

The members of the councils include the heads of universities and hospitals, local elected officials, and labor and business leaders—all handpicked by the governor’s office. The councils make recommendations about which projects should receive funding, although state agencies make the final decision.

The system has come under fire for allowing widespread conflicts of interest, as many council members represent organizations which receive REDC funding. A 2014 analysis by Politico New York found more than 1,500 instances where council members had to recuse themselves because of a conflict. Several council members have also given to the governor’s political campaigns.

“It seems to me there’s a lot of cronyism that goes on,” Assemblyman Fred Thiele, a Long Island Republican, said at a budget hearing in February.

The Assembly is currently considering legislation that would require REDC members to complete annual financial disclosure statements; the state’s budget director has called this “an absurd and a not-so-subtle effort to end the REDCs.”

The regional councils’ track record on creating jobs is also unclear.

A 2015 report by the Citizens Budget Commission found that inadequate reporting made it almost impossible to tell how well projects were doing. Of the fraction of projects for which employment figures were available, none created as many jobs as promised.

Another report in 2016 found that, although all 10 regions prioritized manufacturing in their development plans, six lost manufacturing jobs between 2010 and 2015.

“The results suggest it may be time for REDCs to rethink their strategies,” the report concluded.

Brian McMahon, executive director of the New York State Economic Development Council, disagrees.

“Overall, I think the REDCs have been effective,” he said. “They have worked because they brought together opinion leaders to talk and develop strategies around economic development.”

Modest job growth

Cuomo has boasted about a turnaround in the upstate economy, going so far as to declare improvements in Western New York’s once hidebound economy “a national success story” due to his Buffalo Billion program.

“The days where downstate flourishes and upstate suffers are over,” Cuomo said in his 2015 State of the State address.

Zemsky, the governor’s economic development czar, told state legislators earlier this year “every region has come a long way from what it was.”

“There’s a lot of data that backs up the incredible progress that’s been made,” Zemsky said.

An analysis of employment data done for Investigative Post by the Fiscal Policy Institute shows otherwise.

New York’s job growth of 9.6 percent—between December 2010, the month before Cuomo took office, and December 2016—ranked 21st among the states and slightly below the national average of 11 percent. New York added jobs at a faster clip than most Northeast and Midwest states.

But that growth occurred primarily in New York City and its neighboring suburbs. Employment in New York City grew by 16 percent, better than all but a handful of boom states. Employment in Long Island and the counties immediately north of New York City increased by 7.4 percent.

The jobs picture was gloomier upstate, where employment grew by an average of only 2.7 percent—a quarter of the national average.

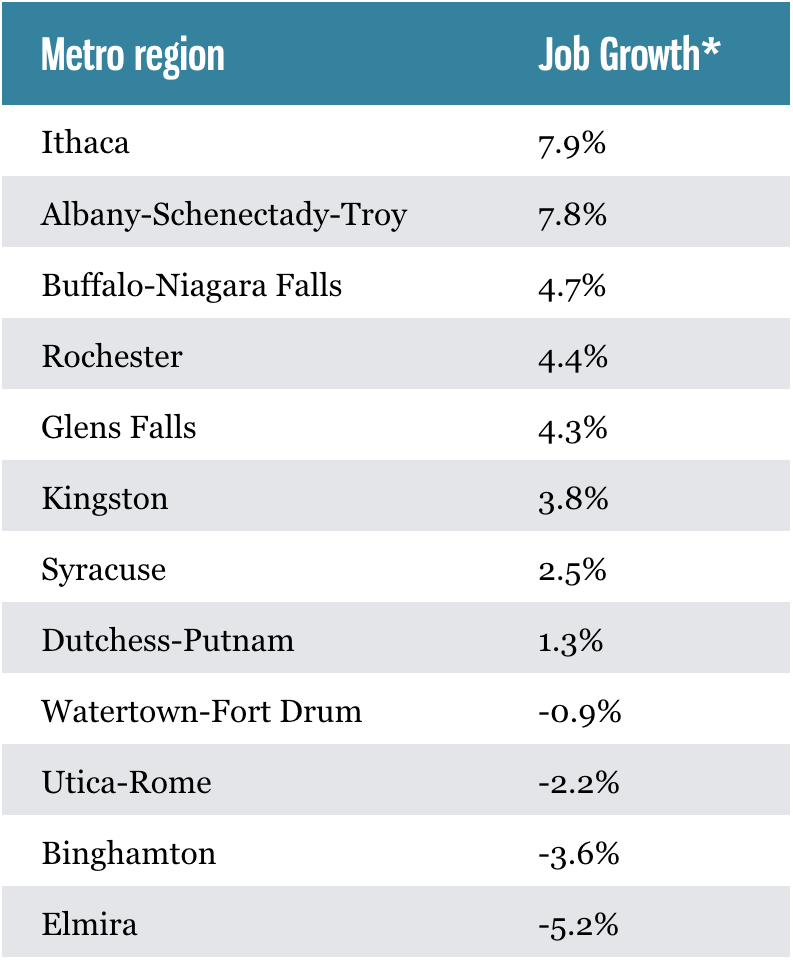

Four of upstate’s 12 largest metropolitan areas—Binghamton, Elmira, Watertown, and Utica-Rome—lost jobs. Only two of the remaining regions—Albany and Ithaca—registered growth that approached the national average.

Sluggish Job Growth in Upstate Metropolitan Areas

Most regions have experienced marginal growth under Cuomo

* December 2010 to December 2016

Source: Fiscal Policy Institute analysis of non-agricultural employment based on data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and New York State Department of Labor.

“The upstate economy has been growing more slowly than other parts of New York State, but it’s not appreciably worse than states that have long been reliant on manufacturing,” said James Parrott, deputy director and chief economist for the Fiscal Policy Institute.

Most of the employment growth upstate involved jobs in lower-paying sectors, according to an analysis with the assistance of the Fiscal Policy Institute of data showing changes between the second quarters of 2010 and 2016.

Employers in low-wage sectors, including retail and restaurants and bars, added nearly 42,000 jobs, accounting for the lion’s share of the 47,500 net new jobs added in upstate during the Cuomo era.

Net growth in middle-income jobs has been flat. Gains in sectors that pay high wages, primarily in businesses located in the Capitol region, have been largely offset by job losses in Central New York and the Southern Tier.

“The economy in the last decade has tended to create low wage jobs,” Parrott said. “What’s missing upstate is growth in middle- and high-wage jobs—professional services, manufacturing, and government. Professional services has been growing, manufacturing hasn’t been growing enough, and together, the growth has not been enough to offset the steep decline in local and state government jobs.”

How does Cuomo’s track record compare with previous governors?

You have to go back to Governor George Pataki’s tenure, from 1994 to 2000, to find find another six years of sustained economic growth uninterrupted by recession.

Job growth statewide, and downstate, was similar under each governor. But, despite Cuomo’s focus on upstate, job growth there was around twice as high under Pataki as during Cuomo’s tenure thus far, 6.6 percent compared with 2.7 percent.

Poor business climate

Economists caution that government can have only a limited impact on a state’s economy.

“The dynamics of the state economy are driven primarily by market forces, not government,” said George Palumbo, professor of economic and finance at Canisius College in Buffalo.

Even so, Cuomo does not have a good track record getting the state to do what it can to make a difference, like fostering a good business climate and making effective use of state subsidy programs.

The governor is credited with lowering corporate taxes and slowing the growth in property taxes, but New York continues to rank among the least-business friendly states in the nation, according to numerous surveys. Critics note that Cuomo-driven initiatives to raise the minimum wage and establish paid family leave have added to the cost of doing business in New York.

“For small business, New York is as bad, if not worse, than it was six years ago,” said Mike Durant, state director of the National Federation of Independent Businesses.

McMahon, executive director of the New York State Economic Development Council, agrees that the business climate remains an issue. But he said Cuomo has taken steps that will yield results.

“I think the investments being made, particularly in innovation and downtown revitalization, will serve our economy and taxpayers for a very long time.”

Others maintain the state’s economic development efforts remain stuck in a cycle of failure, the byproduct of both market forces and government policy.

“Poor job creation, poor return on investment,” said Deutsch of the Fiscal Policy Institute.