Art and Humor at the Albright-Knox

Every thing in this world…is big with jest, and has wit in it…

—Tristram Shandy

A problem with the humor and satire in art exhibit at the Albright-Knox is finding where it starts. That is, if two minutes after you were told at the reception table that it is in the link passageway to Clifton Hall, so heading leisurely in that direction, while having a look at other works along the way, you forget.

Because having a look at other works along the way, you see humor and satire everywhere. Like the Sigmar Polke work with medieval caprice figure—human head and monster animal body transforming to elaborate plant form tail—embedded in what looks like a honeycomb. Or Robert Colescott’s tongue-in-cheek compendium of black folk stereotypes ranging from jungle voodoo figure—reminiscent of one of Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles ladies—to black athlete to black mammy with squalling baby. Or Frank Moore’s panorama view of Niagara Falls and rising mist cloud of industrial pollutant chemical compound names and symbols entrained in the mist. Comic if not tragic.

Till you go back to the reception table and ask again.

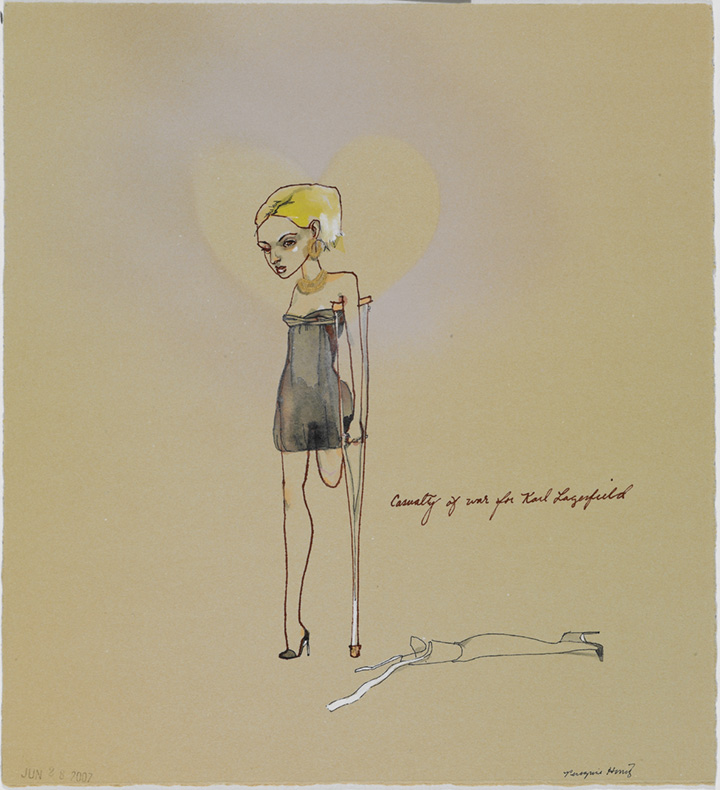

Peregrine Honig (American, born 1976). Casualty of War for Karl Lagerfield, 2007. Watercolor and ink on paper, sheet: 11 ⅛ x 10 ⅛ inches (28.26 x 25.72 cm). Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Arthur B. Michael, Charles Clifton and Norman E. Boasberg Funds, by exchange, 2007 (2007:30.1). © 2007 Peregrine Honig. Photograph by Tom Loonan.

The exhibit proper items range from 19th-century-style sociopolitical satire drawings—essentially pen and ink cartoons—by artists Honoré Daumier and James Ensor, to Claes Oldenburg’s whimsical drawings on topics such as an ice cream cone dropped from an oil derrick and body buildings, that is, buildings in the form of body parts, to Nancy Dwyer’s message painting in garish colors and happy font letters amid soap bubbles, casually instructing the viewer to “Kill Yourself.”

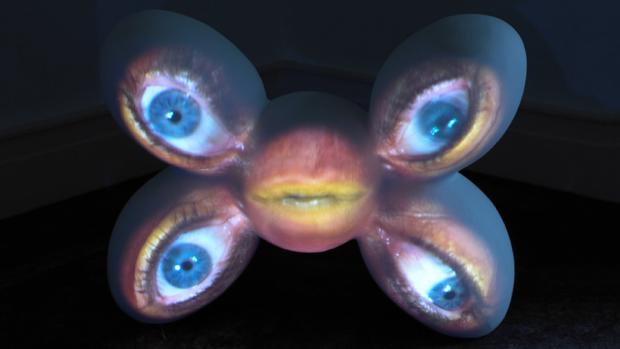

From funny witty—several of Hollis Frampton and Marion Faller’s take-offs on Eadweard Muybridge’s proto motion picture photo sequences of human or animal activities against a background grid—the Frampton and Faller series show vegetal motion, for example, beets assembling, or scallop squash revolving, or carrot ejaculating—to funny inscrutable—Tony Oursler’s sculptural assemblage of four huge disembodied eyes that blink and look left and right and up and down, surrounding a disembodied mouth that rants nonsensically.

The disembodied eyes and mouth piece edges a little into the grotesque. A piece that combines grotesque and elegant is Portuguese artist João Onofre’s video of a man in a rubber mask tap-dancing through the streets and into subway tunnels of some unidentified modern city—maybe Lisbon—while onlookers pretend not to notice but can’t help being amused. Dancing like Fred Astaire. But we only see him from behind, until at the conclusion of the piece he steps into a subway car and turns and we see the mask face-on. A little like the glimpse we get of the mother at the end of Psycho, only this time for an interminable minute, until the subway car door closes and the train pulls away.

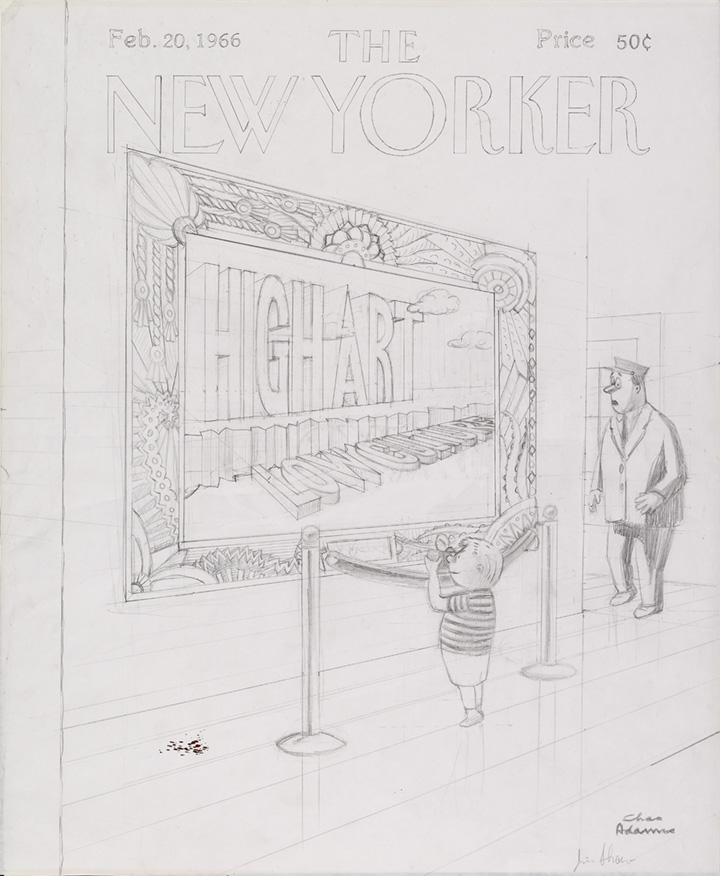

Jim Shaw (American, born 1952). You Break It, You Bought It, 1988. Graphite and ink on paper, sheet: 17 x 14 inches (43.18 x 35.56 cm). Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Gift of Serena Rattazzi in Memory of Mario C. Rattazzi, 2006 (2006:20). © Jim Shaw.

Intertextual reference is a mainstay humor and satire strategy. As in a Jim Shaw drawing for a New Yorker magazine cover featuring an imagined cartoon by New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams of a scene in an art gallery with a painting contrasting the phrases “high culture” and “low culture” in contrasting text lettering à la New Yorker cartoonist Saul Steinberg. High culture as in the art gallery in the cartoon—a lot like the Albright-Knox Art Gallery—and art typically shown in such galleries. Low culture as in cartoon drawings. Works of artists like Shaw and Addams and Steinberg. But what about Daumier and Ensor? What about this show at the Albright-Knox? And where does a publication like the New Yorker fit in on the “high” and “low” scale?

Along the way, Marcel Duchamp’s little metal cage of what look like sugar cubes, Julian Montague’s stray shopping carts taxonomy work, Peregrine Honig’s fashion world satire drawings, Jon Pylypchuk’s ambiguity to disambiguity puzzler.

The exhibit is called Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before. It runs through March 19.

Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before

Albright-Knox Art Gallery

1285 Elmwood Ave, Buffalo