The Grumpy Ghey: Godless Brother in Love

The email sounded so promising, too. But it was a press release, and press releases are supposed to whet one’s appetite whether or not you’re actually going to get fed.

The email sounded so promising, too. But it was a press release, and press releases are supposed to whet one’s appetite whether or not you’re actually going to get fed.

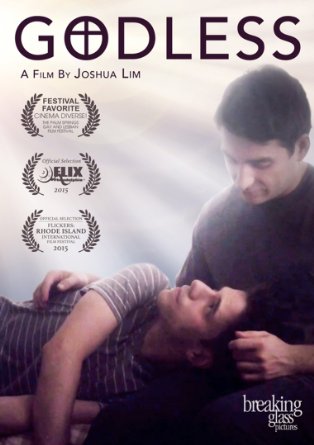

Joshua Lim’s 2015 film Godless was released on DVD and to streaming/online rental outlets two weeks ago, after a promising festival run last year. The story revolves around siblings, the Flanigan brothers, who have been involved in a supposedly intense love affair since around the time of puberty. But when one brother, Steven, leaves for college, the other, Nate, is devastated. His last year at home is spent pining for his brother’s withdrawn affection. When Steven returns home for vacation, Lim leaves the details vague.

Following the death of their father, Nate moves back in with his mom, having gone off to college in the interim. He takes a job as a personal trainer at a local gym and flounders: Nate’s character fails to launch. It becomes clear as the movie trudges on that his attachment to his brother has him stuck.

When their mother passes, the brothers are reunited at home for the first time in years. Lim does a good job at building tension, but that’s about all he does well. Tension mounts again and again, never really coming to a head or allowing any steam to escape. It just gathers, leaving the viewer in a pickle, much like Nate’s character. It’s suffocating.

The acting does little to help this. There’s no tangible chemistry between Steven (Michael E. Pitts) and Nate (Craig Jordan). We are told—but not very effectively shown—that they’ve been lovers. Their touching doesn’t seem familiar; the kissing is awkward and completely lacks electricity. There’s no passion to the limited physical interplay we see between them. It just isn’t believable. At times, they seem like guys on a first date, as if they’re uncertain of their attraction to one another.

Making matters worse is the arrival of Steven’s new boyfriend, Ray (Jefferson Rogers), who looks like a model for a Paul Frank chimp and has all the personality of a shower curtain liner. Ray represents the rest of the world—the possibility for better adjustment, healthier relationships, etc. If the intended effect is to make this seem attractive, it doesn’t work. Ray’s annoying. I spent the rest of the film wishing he would go away.

After the loss of his mother, Nate is really in a state. Steven teeters on the edge of giving in to old patterns and trying to be the voice of reason, repeatedly reminding his brother that they cannot sustain their romance. A confusing addition to the mess is Nate’s co-worker, Trent, played by Garrett Young. Trent and Nate apparently hooked up, and Trent is interested in dating Nate. When they express their love for one another, however, it too is unbelievable. We’re told there’s a history between them, but we’re also led to believe they had just one sexual encounter. Love seems like a long shot.

Lim’s strategy is unclear. Zero camera movement, limited angles, stilted dialogue—it’s headache-inducing. (Godless should have pursued sponsorship from an over-the-counter pain reliever.) He often lets time play out in wide shots of empty space with nothing even remotely compelling in the frame. One reviewer said, “The filmmaker has a unique directorial approach that conveys something of apathy toward his audience,” which leads me to wonder: At what point is it safe to say that Lim’s approach is just lame and lazy? I’m all for artful choices, but to me that just sounds like a way of avoiding the truth.

Perhaps Lim might have done better to give in to his apathy altogether and simply not make the film.

What the Flanigans are dealing with is something called sibling consanguinamory. And many gay boys (some basically straight ones, too) have fantasized about it. Before anyone calls me out, this is not about sexual abuse, molestation, coercion, intimidation, etc. This is about consensual sex between siblings who are close in age. It happens, and for every time it’s actually happened, I’d posit that two dozen other adolescent guys have thought about it.

It really isn’t so strange. You and your brother are a year or two apart. He develops before you do, and you get to watch as his body changes. Maybe you look up to him. Maybe he’s athletic and you aren’t. Maybe you share a room and you hear him masturbating at night. Maybe you even resemble each other, adding a touch of the old narcissism to the mix. It’s not a comfortable topic, but it’s real. In the case of the Flanigans, both brothers are gay. This also isn’t as statistically unusual as one might think.

Do we applaud a writer-director for taking on a taboo topic even when they drop the ball? Tough call. It feels like a missed opportunity. I’m not a film director, but it seems to me that Lim could’ve spent some of the time he put into building tension into building multi-dimensional characters instead. We need reasons to care about these people, about their choices and their reasons for making them.

The ending is just as bad as all that came before it. Steven begins sneaking into see Nate after Ray falls asleep. In what functions as the film’s climax, Ray hears them having sex when he listens at the door. (Ray hears them, we don’t.) The couple leaves the following day. The most cathartic moment of the entire film occurs when Nate is left home alone, without his mother or brother. The emptiness is palpable.

You’re left hoping that Steve will dump Ray and come home to his brother. Instead, Steve comes clean to Ray and agrees to cut all romantic ties to Nate once and for all. Propriety wins, but at what cost? Nate stages a suicide attempt, complete with farewell video, only to have Trent show up at the door—a symbol of the future. It’s not a satisfying tomorrow. Not even a little.

There’s a larger theme at play, which speaks to the film’s title. The idea of a godless universe gets brought up briefly in a conversation between the brothers. Steven quotes the late antitheist writer Christopher Hitchens, while his brother contemplates the existence of an afterlife. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what Lim is going for here, but if there’s no god, then we are not beholden to the Judeo-Christian model of right/wrong/sin/consequences, etc., but rather are left to wrestle with our most base, infantile desires. Exactly how this impacts the situation at the Flanigan residence is left a mystery. Nate does often behave like a baby, but it’s his brother who believes in a godless universe. And so it just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.

Perhaps the devil’s in the details. By putting the sibling romance in the past, Lim gets to avoid dealing with it directly for the majority of the film. It’s the elephant in the room, for sure, but he attempts to get away with just letting it lay there like a bored bottom. A more effective means of storytelling might have been to move back and forth in time, but it’s pretty clear the actors wouldn’t have been able to handle it. Alas, we’ll just have to wait for another filmmaker to give this topic a shot, in which case Godless serves as an excellent reference on what not to do.

*“Godless Brother in Love” is also the title of a beautiful song written by Sam Beam, a.k.a. Iron and Wine. To my knowledge, the song and the film have absolutely nothing to do with one another, but it seemed a fitting title, so I borrowed it. I don’t think Sam would mind.