Holiday Ghost Stories: The Case of the Vanishing Spirits

The average American stereotypes Halloween as the prime spook night and is surprised to hear that Christmas Eve was ever its rival. In most of medieval Europe, Christmas Eve was the proverbial “miracle” night. By the Victorian Era, Christmas Eve had become a night of supernatural storytelling in many English-speaking societies. The tale to come is the fourth in our series of holiday-season ghost stories about East Aurora’s Arts & Crafts Movement-inspired Roycroft Campus. It was recalled for me in the mid-1990s during the interviews for my first book, Shadows of the Western Door (1997).

Neither Christmas Day nor Christmas Eve fall on the winter solstice. Still, Christmas is a winter solstice event. It was appended onto cross-cultural midwinter festivals that had been in place long before the day became the big deal for the Christians.

The solstices are the days of longest or shortest daylight. “Solstice” is a Latin-derived word. It means, basically, “sun standing still.” The explanation for this is simple: because that’s what it looks like to you if you happen to be overlooking the horizon and plotting the sun’s drops or rises, as we know the old-timers did.

The points at which the sun sets and rises cross the horizon at a fairly constant rate until they come to their extremes, the solstices. Then they start coming back toward the middle; but they start slow. In fact, at those end-points the change in the sun’s position is negligible for days. Day length is slow to change, too. The difference in daylight a week before one of the solstices and a week after is about a minute in our part of the world.

The dates of the solstices can vary. December 20, 21, 22, and 23 are all days on which the winter event might fall. The solstice is almost always on December 21 or 22, though. It will be centuries before we see one on December 23. (FYI, this year the solstice is on December 21, the day this issue of The Public comes out.) Both solstices were powerful events to our ancestors, and an enormous legacy of folklore and tradition has built up about them.

The Christmas season was significant at the Roycroft Campus during the stewardship of its spiritual-not-religious founder Elbert Hubbard (1856-1915), who arranged week-long parties and celebrations around the holiday. Prominent people came from far and wide to attend them. One wonders if these legendary conferences could have some psychic aftereffect. The Roycroft Campus comes to light for “miracle stories” every Christmas season. This one comes from the early 1980s and the age of Ali Baba’s, the Roycroft Inn’s thumping basement disco.

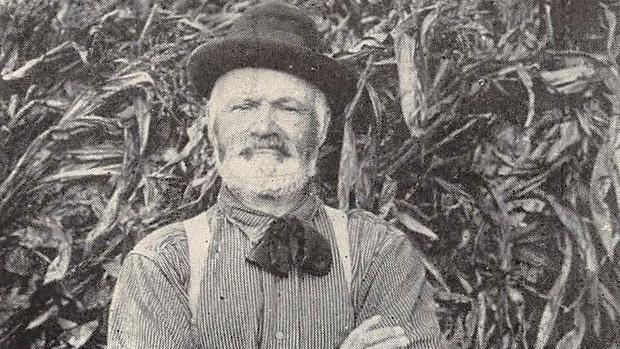

“Ali Baba” was Anson Alfonso Blackman (1839-1926), the original Roycroft handyman. At another time I can tell you how he got his nickname. Blackman was a virtual serf whom Elbert Hubbard made into an international star by portraying him as a character in his books and magazines. A significant turn-of-the-century reading public thought of the unassuming “Baba” as a rustic philosopher because of the proverbs Hubbard attributed to him. Since the entrance to the Roycroft Inn’s basement pub was Blackman’s former toolshed, the name Ali Baba’s seemed a good fit.

The eastern section of Ali Baba’s was at the foot of the celebrated tower in which it was rumored that Roycroft founder Elbert Hubbard (1856-1915) had held his “magical” ceremonies, which were most likely Rosicrucian meetings and gatherings. The Rosicrucians are a philosophical group whose ideas are probably best described as spinoffs of the general Western tradition of mystical ideas called “the Hermetic-Cabalist tradition.” I refer to it as “Da Vinci Code stuff” during talks and tours so people can get grounded. Rosicrucianism’s most familiar ideological cousins are probably Medieval alchemy and Freemasonry. In the mythology of Rosicrucianism’s predecessors, the ability to summon an elemental or some other sort of protective bogie was fundamental for the masters. We see this custom in legend all over the world, by the way, that important objects and sacred places are protected by curses and ominous beings. Potential thieves or transgressors are warned first, usually by getting the heck scared out of them.

In the early 1980s the big historic masterpiece we call the Roycroft Inn was part of the Niagara Frontier’s original restaurant empire, that of the Turgeon Brothers. The story goes that a problem was discovered at Ali Baba’s bar, one I call “The Case of the Vanishing Spirits.” Records of liquor dispensed did not match the records of liquor sold. Many bars encounter the same problem, and seldom to the advantage of the establishment. Had the inn’s fabled ghosts developed a taste for liquor? It’s more likely that Ali Baba’s bartenders were giving shots to their friends, as well as to attractive clients. (Ali Baba’s had the reputation of a Woodstock West.)

The solution seemed to be a character I call on my tours of East Aurora “the Macho Young Bartender”—chest hair, gold chains, and open-to-the-navel shirts. He had established a reputation for both toughness and honesty at other Turgeon Brothers establishments. He was hired as manager of Ali Baba’s to straighten things out.

At his first meeting he addressed the full staff. Not only would he settle the case of the missing whiskey, he said, but he didn’t want anything as silly as ghost stories getting in the way of people doing their jobs. As a test, he called out the ghosts of Roycroft to mess with him if they chose. He pounded on his bare, furry chest until the medallions clattered. There were many witnesses. You can probably sense another shoe to drop.

It fell a day or two after Christmas, on an early weeknight that I am told may have been a Tuesday. It was after one in the morning, so late that even the riotous Ali Baba’s was dark and still. Mister Macho was in the first-floor kitchen helping his colleagues close up when he announced that he was headed off to use the mens’ room in Ali Baba’s at the foot of the tower. A minute after he left, it seemed, he was back in the kitchen, white as a sheet and yammering like the terrified Ralph Kramden of the Honeymooners: “Hominah, hominah…”

He told his fellows a strange story. As he had stood at the urinal, the lights flickered. He felt a chill on the back of his neck and a rising sense of fear. He looked behind him to see something dark and cloudy starting to manifest. It seemed to be resolving itself into a cowled figure with eyes the size of chicken’s eggs. That, though, was as long as he looked.

He tore out of there and up the stairs to the kitchen, safe and untouched. His terror wasn’t funny, though the people I interviewed could never think of the story without laughing. Mr. Macho had run out so fast that he hadn’t zipped up his pants. What he had on for undies were powder-blue silk boxer shorts. Now you know what the macho guys wear. I would consider this the easy way of finding out.