The Mule

Never believe any performers when they say they’re going to retire. Okay, maybe ABBA: If they could turn down a $1 billion offer to do a reunion tour, I guess they really mean it. But for anyone else who plays to the paying public for a living, retirement generally only means kicking back until they either get bored or an interesting offer comes along.

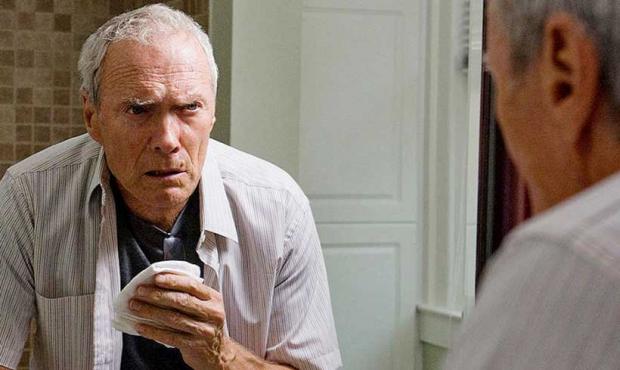

Clint Eastwood has of course been going strong as a director, but he was supposed to have retired from acting a decade ago after Gran Torino, a movie that certainly looked like a career-ending statement. But there he was back onscreen as a baseball agent in 2012’s Trouble with the Curve, and here he is again as a 90-year-old drug-runner in The Mule.

Nick Schenk (who also wrote Gran Torino) based his script on a true story about an elderly horticulturist in need of money who fell into a job transporting drugs for Mexico’s Sinaloa drug cartel. It’s only a loose adaptation, and Schenk doesn’t seem to have been terribly concerned in any of the things that would seem to be most interesting about this story. For one thing, Earl Stone’s age hardly enters into it: He could as well be 80, or 70, or even 60. Nor do we get many details about the job, which apparently doesn’t require him to cross the Mexican border. (Why the cartel is willing to pay such big bucks to drive drugs from Texas to Chicago is a mystery.)

For a good chunk of the film, it seemed like one of those movies that Eastwood the director took on simply because it was the time of year when he makes a movie and he didn’t have any better script on hand. It rambles on amiably enough, as Earl keeps finding new uses for the easy money the job offers. Eastwood may be too fond of presenting the old guy’s flaws, especially the kind of casual racism that his generation didn’t realize was offensive, but it’s hard to resist the sight of him tooling along in his truck whistling “More Today than Yesterday.”

It isn’t until The Mule’s third act that we see what drew Eastwood to this material. Earl has a bad history with his family, having neglected his ex-wife (Dianne Wiest) and daughter (played by his own daughter Alison) in favor of—well, anything that would get him out of the house. But the money he is earning allows him not only the chance to mend old wounds, but the ability to see just how deep those wounds run. The scenes he plays at his wife’s deathbed are as good as anything he has ever done as an actor, and might even net him an Oscar nomination despite the weaknesses of the rest of the movie. (How much he drew on his own history for this is, of course, open to speculation.) It’s not a great movie, not by a long shot, but there’s great stuff in it from an American filmmaker who is still full of ambition and surprises.