GreenWatch: Interview with Orin Langelle

GreenWatch Guest Article by Global Justice Ecology Media Coordinator, Kip Doyle

The End of the Game: The Last Words from Paradise – Revisited

¡BuenVivir! Gallery 148 Elmwood Avenue, Buffalo

Through December, 17 2015 with Closing Reception & Solstice Party 6–9 p.m.

Wine & Hors d’Oeuvres – Free and open to the public

There is just one last chance (for now, at least) to view The End of The Game: The Last Word from Paradise, Revisited exhibit. The exhibit marks the 50th Anniversary of famed photographer and artist Peter Beard’s book, The End of the Game, and features photos by photojournalist and ¡Buen Vivir! Gallery Director Orin Langelle documenting Beard’s 1977 End of the Game exhibit, the first one-person show at Manhattan’s International Center of Photography (ICP). The exhibit closes Dec. 17.

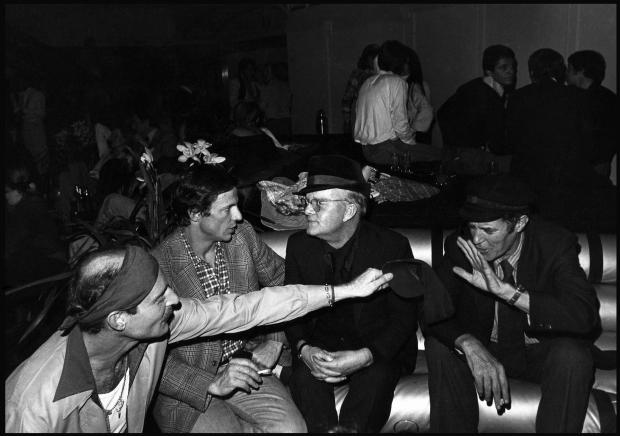

Langelle shot the photos over four months during the installation, opening and parties surrounding Beard’s exhibit. Visitors will recognize many cultural icons in the photos, including Andy Warhol, Jackie Kennedy and Truman Capote. The juxtaposition of these with Beard’s work documenting the impacts of western-style “conservation” in Africa–including the deaths of 35,000 elephants–creates a broad and compelling exhibit in which viewers are taken from the desolation of the African flatland to the glitz of Studio 54 in its legendary heyday.

The closing is unlikely to be the finale for The End of The Game–Revisited, however.

“Nejma Beard is working on having all or part of the exhibit displayed at the Gordon Parks Foundation Gallery outside of Manhattan,” Langelle said. “Also Peter is having a one person show this June at the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton and Nejma has asked me to include some of my photos in it.”

¡Buen Vivir! Gallery, at 148 Elmwood Ave., will host a closing reception for The End of The Game, as well as a Solstice Party for Global Justice Ecology Project, on Dec. 17 from 6-9 p.m. The event is free and open to the public. For more information visit ¡Buen Vivir! Gallery

What made you decide that this was a good time to bring these photos from the 1970s back out and show them to the public?

This exhibit came about because a lot of coincidences. In the process of archiving my four decades of photojournalism, I came across a package of photos I shot during the first one person show at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in Manhattan: The End of the Game – The Last Word from Paradise by Peter Beard. The photos were shot over four months of documenting the installation, opening and parties at ICP and Studio 54 surrounding The End of the Game.

Then Nejma Beard, Peter’s wife and Executive Director of the Peter Beard Studios in New York City called and told me that a 50th Anniversary edition of Beard’s book The End of the Game was being printed this fall. Nejma wound up getting me four advance copies of that 50th edition book for the exhibit. Taschen is printing it in a very limited run of 5,000 books. (Our advance copies are numbered 0000.) It is quite an impressive work. Filled with incredible photographs Peter shot throughout the 1950s and 60s in Africa, as well as photos of the colonists, settlers and adventurers who led to the beginning of the end of wild Africa.

But I had originally planned a fall show on globalization issues for the ¡Buen Vivir! Gallery to coincide with the UN Climate talks in Paris that just concluded last week.

My wife Anne Petermann, however, made the point that the issues that Peter Beard covered in The End of the Game were directly relevant to the climate talks, and suggested I use the work I shot at ICP as the fall exhibit. So I did.

How did you connect with the International Center of Photography to shoot the first one person show there? I was living on the Left Bank in Paris in 1975 right after the Vietnam War as an artist (photographer) and ex-pat. I worked with a publication that catered to other English speaking people in Paris called Paris Life. It was small and struggling but it later became Paris Voice and became a success.

One day the editor told me the CIA was trying to buy out all foreign English language papers and he was approached to do so but did not want to. I never was a fan of the CIA, so I thought it was a good time to get out of Paris for awhile. I went to Spain a week after the Fascist dictator Francisco Franco died. I arrived in Barcelona to see every street corner occupied by a soldier with what looked like an old Nazi helmet, armed with a machine gun. At sunset the fascist soldiers would turn toward Franco’s tomb and give the right outstretched arm salute in his honor.

Not liking fascists any more than the CIA, the next day I took a boat to Ibiza in the Mediterranean. Then after a couple of days there I hopped a ferry to Formentera, and spent some time examining what my future might hold on that close by small-island.

When I arrived back in Paris I learned about the incredible work of Robert Capa, famed photographer, and co-founder of the Magnum Photo Agency, who documented the horrors of war. He died in Indochina when he stepped on a landmine. But I learned that his brother Cornell Capa ran the International Center of Photography in Manhattan. I was determined to go there. And in 1977 and 1978, I did.

What were your impressions of Peter and the people he spent time with during his show? Were there any funny interesting or candid moments?

One of my first impressions was smoking a joint with Peter and a woman in the hotel where Peter was staying; then recognizing she was an actress from a film I saw in a theater the previous night–in director Luis Buñuel’s final movie.

Predictably Peter’s circles during the ICP period included the famous – such as Jackie Kennedy Onassis, her daughter Caroline, Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, Kurt Vonnegut, model and actress Lauren Hutton along with others, including influential New York Times Art Director Ruth Ansel and The End of the Game curator and designer, Marvin Israel.

Peter was also unpredictable in many ways.

One day I was sitting on a step with Peter in one of the galleries at the ICP gazing up at a huge Christmas tree that had no ornaments or lights. Peter asked me to find a photo I shot of him stabbing his arm to draw blood–a technique he used to “enhance” his photos. I brought the photo back, and Peter grabbed the photo and started ripping the edges off. Then, when he had the look he wanted, he stabbed his arm with a pen, smearing his blood all over the photo. We then tied some fishing line to it and hung it on the tree. Peter looked at the “ornament” and said, “It’s about time it got decorated.” And all of this was in front of a very bewildered group of museum goers.

Where does Peter Beard’s message fit into today’s world regarding climate and climate solutions?

Beard’s controversial views on ecology–and his critical perspective on ‘human exclusion’ style conservation back then, are just as relevant today. Consider the UN Climate Conference in Paris, France that just ended. A similar model of “conservation” was promoted there to “conserve” forests as carbon offsets to allow big polluters to keep polluting. Indigenous peoples and local communities that historically maintained those forests would be evicted in order to protect the carbon stored in those forests; another social and ecological nightmare.

In Zara’s Tales, written in 2004 for Nejma and his daughter Zara, Peter succinctly summed up human exclusion and modern conservation:

For centuries these bow hunters lived, and lived well, among the elephants and rhinos. A natural order was established – coexistence – symbiosis! They all were surviving nicely, in balance until the white man came along to save them. The whites staked out protective boundaries, arrested the hunter-gathers and upset the balance. Concentrated populations of reproducing pachyderms overpopulated and overate their food supply. Disaster was then at hand.

Peter just didn’t come to that conclusion in 2004 – I believe he came up with that fifty years ago. If those who have gained power and dictate the preservation of nature and how forest inhabitants are to live, would have listened to what Peter said fifty years ago and what Indigenous Peoples’ having been saying from time immemorial, maybe we wouldn’t keep plunging toward climate catastrophe.

What kinds of responses have you gotten from gallery guests?

People who understand the show seem to really enjoy it and get a lot out of it. I’ve been told it’s the best exhibit we’ve done yet.

What kind of feedback have you gotten from Peter and his family?

Peter is 77 and recovering from a stroke. He has not had any hands-on involvement with the exhibit, but I’ve been working closely with Nejma Beard and the rest of the Peter Beard Studios. I’m sure Peter shares his ideas with them. Nejma has always been supportive. In 2006 Anne and I were going to Nairobi, Kenya for the UN Climate Conference and Nejma said that afterwards we should stay at Peter’s Hog Ranch, a forty-acre tract of land next to the ranch of Karen Blixen (Out of Africa fame). I’d heard of Hog Ranch since 1977 when I first met Peter and it was quite an experience to stay there and view the wildlife, including warthogs, giraffes and dik diks, while gazing at the Great Rift Valley and the Ngong Mountains. We got there just after Mick Jagger left.

After the exhibit opened here in Buffalo, Nejma and Peter’s daughter Zara wrote to Anne and me, thanking us for understanding what her father was actually trying to get across regarding nature and failed conservation schemes.

What is the future of the show?

“As I mentioned, Nejma Beard has been really supportive. She’s been working to have all or at least a large part of it go on display at the Gordon Parks Foundation Gallery outside of Manhattan,” Langelle said. “Also Peter is having a one person show this June at the Guild Hall Museum in the East Hamptons on the upper part of Long Island close to Montauk and Nejma has asked me to include some of my photos in it.”

What inspired the creation of the ¡Buen Vivir! Gallery?

I’ve photographed Indigenous Peoples and social justice struggles all over the world over the past several decades. In Mexico, Central America and South America, the social movements have an expression “¡Buen Vivir!”

We named the gallery, ¡Buen Vivir!, after this expression, which means life in harmony between humans, communities, and the Earth–where work is not a job to make others wealthier, but for a livelihood that is sustaining, fulfilling, and in tune with the common good.

The ¡Buen Vivir! Gallery was founded to present an historical look at movements for change, struggle and everyday life. It is designed to counter the societal amnesia from which we collectively suffer—especially with regard to the history of social and ecological movements and issues, and to inspire new generations to participate in the making of a better world.

So what is next for the gallery?

After December 17, we’re going to close the gallery until March 4 when we open Climate Change—Realities and Resistance. The exhibit tells the story of the growing global demand for climate justice, and features images from photographers from Australia, Croatia, Romania, the UK and the US. This exhibition was on display in Paris during the UN climate COP 21 negotiations, at the Climate Action Zone (ZAC), which just ended.

Along with the photography exhibit we’ll also show work by artist Ashley Powell. About Ms. Powell’s last art project, The New York Times wrote on September 19: A graduate student at the State University of New York at Buffalo hung ”black only” and “white only” signs around campus this week as part of an art project, which she said was intended to provoke a searing conversation. And indeed it did. The signs shocked students and jolted the university at a time when discussions about race and race relations have been prominent in the news. The student, Ashley Powell, who is enrolled in the university’s Art Department, began posting the signs, made of cardboard and paper, shortly before noon on Wednesday, she said, hanging 17 of them in several buildings on campus, next to elevators, water fountains, benches and bathrooms. Within about an hour, university police began receiving phone calls from alarmed students, according to a student newspaper, The Spectrum.Some students called the signs traumatic and said they made them feel unsafe. At this time I have no idea what Ashley is going to present. That’s up to her. We don’t dictate to an artist we’re working with what art is. We’re a controversial gallery, so… The gallery is now connected to Global Justice Ecology Project and we use the exhibits there as a means toward awareness raising about the issues GJEP has been involved with over the years, and as a way for people to get involved. There is more about GJEP at globaljusticeecology.org