A Day That Still Lives in Infamy: FDR’s Legacy in Western New York

December 7, National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day, is a day to remember and honor all those who died in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The flag of the United States flies at half-staff until sunset in honor of those who paid the ultimate price in the service of their country. Remembrance Day is also a time to acknowledge the sacrifices and resilience of all those who survived the attack and fought back, the many American citizens who endured years of war—right after surviving years of tremendous economic hardship during the Great Depression—including the people of Western New York. As seen recently in the latest Ken Burns PBS documentary, The Roosevelts, we are aware more than ever of the leadership and strength of character Franklin D. Roosevelt provided to a much-troubled country. What should also be remembered here in our community are the stories of the people who lived in our region during the 1930s and 1940s, and who heartily responded to FDR’s example of personal courage and national pride and spirit, demonstrating their willingness to fight back against the fears of foreign aggression and domestic hardship in order to preserve what was important to them. The nation and this region both bounced back from the economic and political turmoil of the times—giving Americans today a sense that the current economic and political uncertainties can be overcome when we work together. The Library of Congress in Washington, DC is a treasure trove of national memories documenting this era, including the role played by people in upstate New York.

FDR and Western New York before the “Day of Infamy”

As early as 1936, people of Western New York had the opportunity to hear Roosevelt talk firsthand about the impending world crisis. FDR’s “I hate war” speech was delivered on August 14, 1936, during an address he gave at the Chautauqua Institution. President Roosevelt communicated to the audience the horrible impression that World WarI had left on him, and his awareness that new fanaticisms and old hatreds were always present and ready to erupt into armed conflict. His words ring with a disturbing resonance today:

I have seen war. I have seen war on land and sea. I have seen blood running from the wounded. I have seen men coughing out their gassed lungs. I have seen the dead in the mud. I have seen cities destroyed. I have seen two hundred limping, exhausted men come out of line—the survivors of a regiment of one thousand that went forward forty-eight hours before. I have seen children starving. I have seen the agony of mothers and wives. I hate war…

Many causes produce war. There are ancient hatreds, turbulent frontiers, the “legacy of old forgotten, far-off things, and battles long ago.” There are new-born fanaticisms, convictions on the part of certain peoples that they have become the unique depositories of ultimate truth and right.

A dark old world was devastated by wars between conflicting religions. A dark modern world faces wars between conflicting economic and political fanaticisms in which are intertwined race hatreds…

Two months later, in October 1936, Roosevelt was in Buffalo to lay the cornerstone for a new federal building, noting that he had been in town “not so very long ago” to attend the dedication of the State Office Building. Both structures, as Roosevelt observed were constructed as part of his public works programs, which he described as “what we Americans had decided was an American substitute for the dole.” The first structure, the New York State Office Building located at 65 Court Street in Buffalo was built in 1932 (renamed the Mahoney State Office Building in 1982 for Walter J. Mahoney, a former and influential state legislator and State Supreme Court Judge). The Federal Building, dedicated by FDR in 1936 is now the Michael J. Dillon Memorial United States Courthouse (a courthouse of the United States District Court for the Western District of New York) located at 68 Court Street in Buffalo. The building was renamed in 1986 in honor of murdered IRS Revenue Officer Michael J. Dillon.

Almost one year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt was again in the region, making stops at various plants, including Curtiss Wright and Bell Aircraft. In his address at Bell, Roosevelt says, “I have been very thrilled in what I have just seen. It seems to me that for a five year old child you are all grown up and doing men’s work and women’s work too.” His inclusion of women as part of the war work effort was a great motivating factor for women everywhere to join the industrial labor forces.

Roosevelt’s speeches in Buffalo emphasize the value of “united labor” and the urgency of maintaining quality aircraft while stepping up production, essentially to support his Lend Lease policy of supplying Allied forces with much needed equipment in their conflict with Germany. The copies of these several speeches made in the course of one day here in the Buffalo area stress the need to keep Americans united and productive.

The Man on the Street: Buffalo, New York

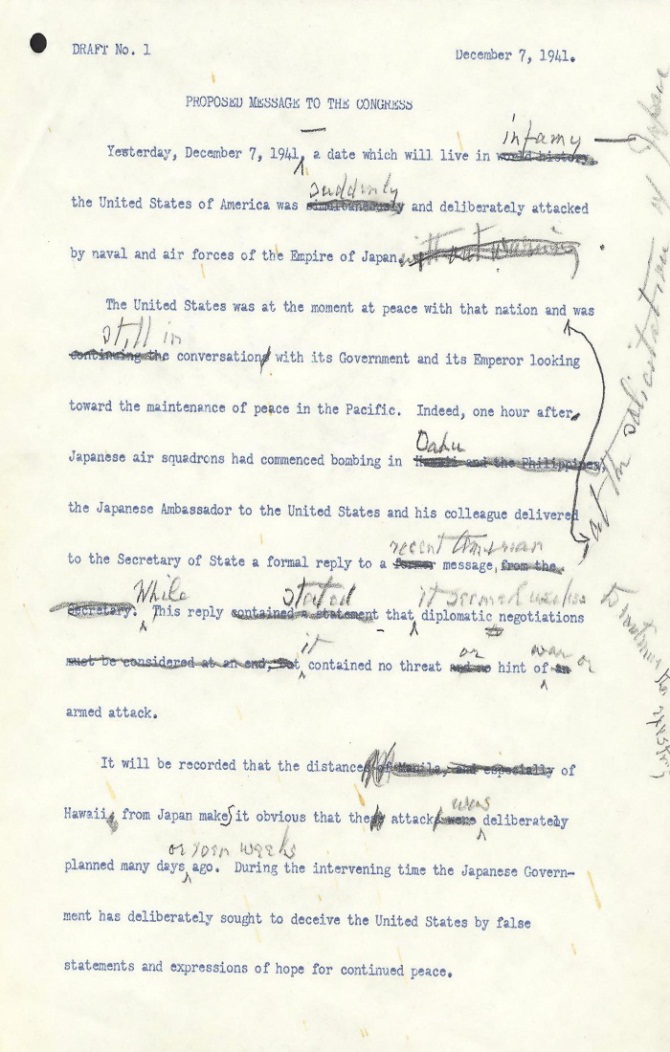

Roosevelt’s “day of infamy” speech—which could very well have been called something else since he edited his original words, “Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in world history…” was quickly followed by a US declaration of war against Japan. Immediately after the attack at Pearl Harbor, Alan Lomax, working in the Archive of American Folk Song (now the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress), sent telegrams to fieldworkers across the country asking them to conduct interviews with regular citizens to get their reactions to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The “Man on the Street” collection includes 12 hours of more than 200 interviews that took place in cities and towns, including four interviews conducted with people in Buffalo, New York. The field person responsible for the Buffalo interviews was Charles T. Harrell, a recent college graduate who had just started work in 1940 as Radio Research Project of the Library of Congress as a writer, recorder, and narrator, but then took a position as head of public service programs at WBEN in Buffalo, New York.

Harrell (who later became an influential radio and television director for NBC and ABC, as well as a noted Broadway director, college professor, and, at the end of his life, a minister) interviewed the following individuals: Dorothy Baer, a widow living with her father on Glenwood Avenue in Buffalo; Frederick A. Hodge, age 65 and living on Linwood Avenue in Buffalo; William Patterson, a 22-year-old recent college graduate from Brown University living with his family on Summit Avenue in Buffalo; and Timothy Sullivan, he was a 35-year-old machinist for Buffalo Foundry and Machine Company, as well as husband and father of one child.

Following the “day of infamy”: the Western New York homefront

Following the “day of infamy”: the Western New York homefront

Women would become famous for the vital role they would play in the war effort, and in Western New York they made astounding contributions to support the United States. Luckily for us, this time of great change was well-documented by the United States Office of War Information (OWI) whose records are preserved and many available online at the Library of Congress. One of the photographers on the OWI staff at the time created an incredibly detailed and humane portrayal of American women at work in the war, much of her story coming from women in this region. Marjory Collins began her successful career in New York City in the 1930s, at a time when it was unusual for a woman to have a successful fulltime job as a professional photographer. Collins joined the Office of War Information in 1941 and throughout the war and after became a feminist activist, who inspired people with her visual stories of the plight of women, including that of “Mrs. Grimm” from Buffalo, New York. (Image: Niagara Falls, New York. Nan Hannegan doing door to door recruiting for women to work in war plants. This program was organized by the War Manpower Commission in cooperation with local war plants who loaned nineteen women workersNiagara Falls, New York. Nan Hannegan doing door to door recruiting for women to work in war plants. This program was organized by the War Manpower Commission in cooperation with local war plants who loaned nineteen women workers.)

Probably using a pseudonym, Collins captures images of “Mrs. Grimm,” a crane operator at Pratt and Letchworth, who was a widow and supporting a family of six children, all under the age of 12. The children and Mrs. Grimm are seen in the course of their daily lives as they attempt to keep a routine and provide a home life in the absence of a mother who is often at work in the factory. According to Collins, the two youngest children live in a foster home during the week while the others stay at school all day, but on Saturday all are home and do all housework.

Women took on almost every aspect of labor at every facility in the area, with little or no prior training. Collins included detailed information to go with her photos including the fact that many of the production facilities were not equipped to handle women employees and so the new female workers would often find themselves taking a break to “powder their noses” in half-finished locker rooms and bathrooms. In several of the major plants, she noted that employees had to bring their own tools to work. This was a bigger challenge for many of the women, just learning the use of tools for the first time. Collins also captured the transition of women coming from the home to the workplace, with images of recently employed women being sworn into the rubber workers union at a Sunday meeting. She notes, “Most of them have never worked before and know little about trade unionism.”

Women took on almost every aspect of labor at every facility in the area, with little or no prior training. Collins included detailed information to go with her photos including the fact that many of the production facilities were not equipped to handle women employees and so the new female workers would often find themselves taking a break to “powder their noses” in half-finished locker rooms and bathrooms. In several of the major plants, she noted that employees had to bring their own tools to work. This was a bigger challenge for many of the women, just learning the use of tools for the first time. Collins also captured the transition of women coming from the home to the workplace, with images of recently employed women being sworn into the rubber workers union at a Sunday meeting. She notes, “Most of them have never worked before and know little about trade unionism.”

At Symington-Gould, makers of tank, ship and railroad parts, women became skin dryers (After head has been put on mold, it is covered with a delta wash which makes a hard finish. Skin dryers dry off this surface with the flame of an oil torch). Many would start out as sweepers as Collins observed, “Most new women employees are given clear-up jobs to start with in order to accustom them to factory life.”

At Republic Steel, Collins stated that women had entirely replaced men as chainmen or “hookers” in the finishing department. “Hookers” placed slings and chains around material to be hoisted by cranes so that it could be moved to another section of the plant or loaded onto freight trains. Women working at Republic Steel also manned huge machines that cut and sliced imperfections from steel castings for gun barrels in the processing department or, they worked inside open hearth furnace as bricklayers’ helpers. Collins reports that “When the end of a chamber is knocked out, there are about 5000 bricks to be lifted and removed. Bricks weigh about eight pounds each.”

There were women working as rollers, inserting tubes into condensers for the Navy at the Ross heater plant; they were grinders and axle lathe operators at the New York Car Wheel Company in Buffalo; they worked with acids as chemical operators at the Niacet Chemical Company; when they weren’t working in the factories, they worked as recruiters of other women workers for the War Manpower Commission.

These images, stories and records of our region’s connection to the FDR era are located in national repositories, but there are so many more like them that you can discover in collections at local libraries, museums, and historical societies. Maybe this Remembrance Day you can visit one of these sites to help remember and keep alive our personal connection with American history.