Millie Chen at BT&C Gallery

Consider wallpaper. Once a staple of home décor, it still sheathes the interiors of many well-appointed households. An ever-present white noise motif, it is the backdrop against which domestic life plays out. Stripping off wallpaper layers is like traveling back in time, glimpsing the fashions, preoccupations, and perceptions of bygone eras. Wallpaper also serves as a metaphor for covering over inconvenient truths; when we conceal problems rather than deal with them, we “paper over the cracks.”

Not Millie Chen.

The artist has a history with wallpaper, one that darkly recalls past events that Chen does not want papered over. For a 2014 exhibition in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, she underscored wartime horrors by creating a wallcovering pattern derived from the etchings of French artist Jacques Callot, collectively titled The Miseries and Misfortunes of War. In 2007, Chen installed slyly modified Chinoiserie wallpaper in public places in Paris, to throw into relief European stereotypes of Chinese culture.

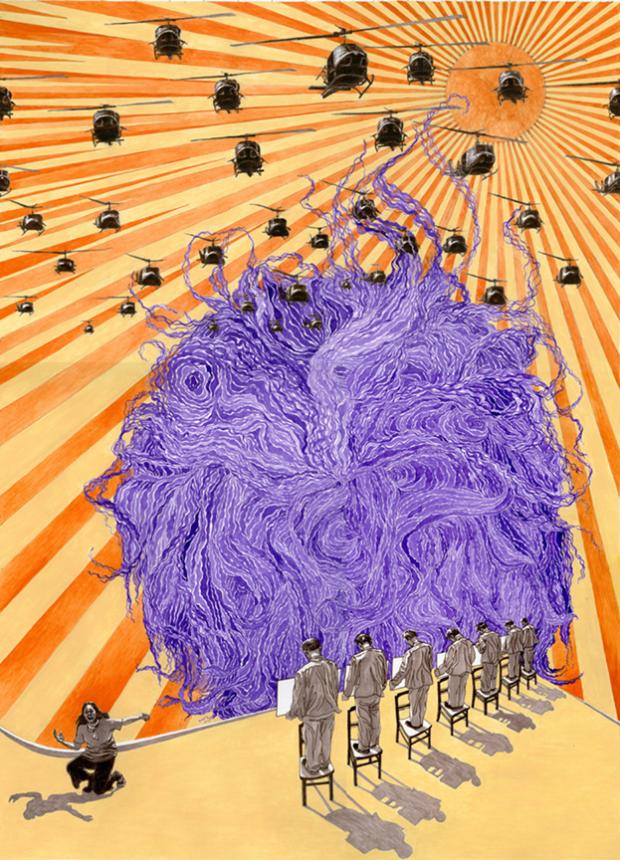

Prototype 1973 by Mille Chen.

In her most recent exhibition, Millie Chen: Prototypes 1970s, now on view at Body of Trade & Commerce Gallery (BT&C), she documents the turbulent events of the 1970s, in 10 original wallpaper designs. Many of the tumultuous social changes we associate with the decade of the 1960s actually occurred or peaked in the 1970s. The Vietnam War escalated with the Cambodian Invasion, stirring widespread protests in America. The trial of Lieutenant William Calley for the My Lai Massacre, and napalm bombing—personified by the indelible image of a severely burned and naked child running down the road in terror—were among the events of that period. The Kent State shootings, China’s Lost Decade, the Soweto Uprising, Bloody Sunday, Black Panthers, Wounded Knee, Love Canal, and the Jonestown Massacre all contributed to a decade of dramatic cultural upheaval. From Hendrix and the Stones to Patti Smith and the Sex Pistols, bell-bottoms to drainpipes, psychedelia to punk aesthetics, the 1970s provided the backdrop, the cultural wallpaper, for Chen’s passage from child to young woman.

Each of her wallpaper prototypes are original works on paper, rendered in various combinations of watercolor, gouache, graphite, ink, and acrylic paint. They are designed as standard pattern repeats, meaning the sides, top, and bottom match so they can be printed in rolls and pasted on a wall in a continuous configuration. Not all are equally successful in this regard; Prototype 1972 would be jarringly wonky as a pattern. No matter; these won’t be mistaken for ornamentation intended to recede into the background of a room.

Though they are displayed as discrete works of art at BT&C, they can be used to produce actual wallpaper should the opportunity arise. For the exhibition, Chen has had Prototype 1977 printed onto rolls, which she uses to paper a corner of the gallery. A lamp, couch, and other furniture items complete the effect, forming a spare approximation of a 1970s-era living room. All that’s missing is a TV set playing Happy Days.

Each prototype represents a single year, referencing events—often horrific ones—that occurred during that period. The year 1970, for instance, goes by the full title Prototype 1970: War, children, it’s just a shot away, Four dead in Ohio, I love Beijing Tiananmen, Excuse me while I kiss the sky. The 31-by-23-inch work is dominated by a fleet of Blackhawk helicopters set against a sun pattern from a vintage Chinese Cultural Revolution poster. A stringy mass of purple haze rises up behind 14-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio, who kneels in her familiar extended-arm posture from John Filo’s iconic Kent State photograph. Next to her, a row of men stand on chairs with their backs to us holding signs, heads bowed in humiliation—enemies of the Cultural Revolution.

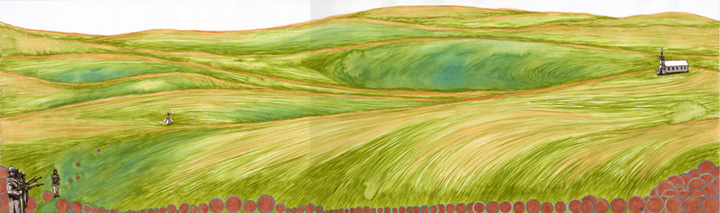

Prototype 1974 by Mille Chen.

Some of the works incorporate vintage design elements: circles and curves, the color orange. One that projects a distinct 1970s vibe is Prototype 1974. In it, Letebirhan Haile, Mairéad Farrell, and Patti Smith stand at the base of a circle that dominates the 17-by-17-inch format, backed by progressively smaller circles of alternating avocado and mauve, evoking both a black hole and kitchen décor.

Through her career, true to the conceptual artist credo, Chen has placed traditional artistry second to the underlying concepts that define her work. She has produced audio, video, and olfactory installations, made temporary wall drawings, built mazes, and painted with pig blood. Her work carries intellectual and political gravitas, with varying degrees of social desolation and apocalyptic apprehension. Conventional aesthetics are beside the point.

Chen’s wallpaper design prototypes are no less politically trenchant or intellectually probing, but they are, perhaps unexpectedly, pleasingly attractive, at times even striking. This adds to their subversive nature, as the visual appeal of the work ironically belies the often heartrending stories they represent. In Prototype 1973, for instance, rolling pastoral countryside is rendered in sinuous brushwork of verdant terrain. A picturesque country church sits off in the distance. Initially, it passes for a pleasantly accomplished landscape. But the tiny solders in the corner inform us that this is no simple bucolic scene, and the title tells us it’s Wounded Knee, site of a bloody standoff between the American Indian Movement and the US Government. Another small figure represents the ill-fated, American supported, Chilean coup that brought Augusto Pinochet to power.

In Prototype 1971 the subtitle says it all: Bangladeshi women freedom fighters smuggle grenades under water hyacinths while May Day protesters congregate in West Potomac Park. Chen renders these disparate and disquieting historical vignettes with restraint and grace, invoking tranquility rather than trouble. This decision to draw interest with ocular palatability, while furtively inserting cold reality, subverts the roll of wallpaper as coverer of inconvenient cracks. We are drawn in, made to recall and ponder extraordinary events, and then perhaps to question.

Prototypes

BT&C Gallery / 1250 Niagara St., Buffalo