Loving Vincent

Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s Loving Vincent is virtually two films, one of them more successful than the other.

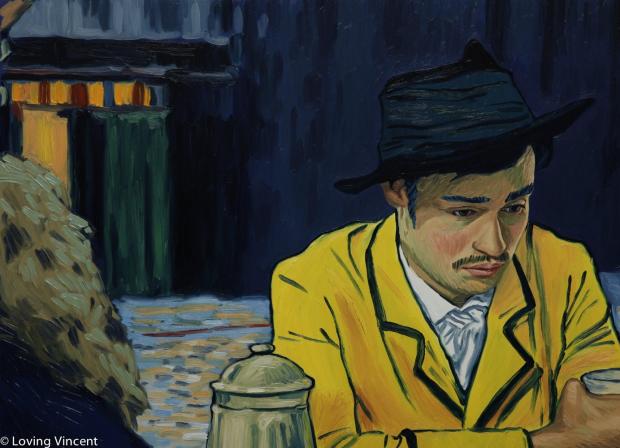

The title’s Vincent is van Gogh, the epically important Dutch painter who remains one of the very few artists whose name is known to a significant proportion of the general public, and whose work can be recognized by many of them. What the filmmakers have wondrously accomplished is to infuse a new kind of life to van Gogh’s famously individualistic painted images. They’ve done it through the employment of a great deal of painstaking handmade art and some technically sophisticated animation. A brief text at the start informs us that 100 artists hand painted the backgrounds, settings, and the costume details and hairdos of the characters. All of this is in van Gogh’s unmistakably characteristic Expressionist style.

The closely allied animation method that places those characters—some of them real people who knew the painter—in those meticulously recreated indoor and outdoor settings involved the combining of live-action photography and a sort of tracing (rotoscoping). The results are more than amusing or engaging; they’re startling and compelling. They’re a small marvel of effectiveness, although the impressiveness fades a little as the movie goes on.

This is because the biopic part of Loving Vincent is less tightly, and ultimately less interestingly done. It sends a young French-village roisterer, Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), on a quest. The lad’s postmaster father (Chris O’Dowd) tasks him with delivering an unsent letter written by the late Vincent to his brother Theo. Gradually, on his longer-than-expected journey, Armand becomes invested in determining the undisclosed causes of Vincent’s suicide, and he attempts to interview people in the northern French town where the artist died. He uncovers secrets and conflicts in individuals’ testimonies, both petty and more significant.

The movie is really a kind of detective story, but it isn’t a very satisfying one. The painter is seen only fleetingly, in retrospective shots, and despite Armand’s sleuthing never becomes a comprehensible figure. We’re left with hints, speculations and reticence. This seems more like confusion and a failure to process the historical record than deliberate post-modern indeterminacy.

But, strangely, this failure isn’t enough to deplete the movie’s appeal. The actors, an international lot, are effective and the recreative imagery is infused with van Gogh’s original vibrantly dynamic, evocative and sometimes unsettling work. On occasion, there’s a sort of subdued challenge in it, an implied tension that may reflect his tempestuous personality. This, in turn, vividly informs Loving Vincent.