Trumbo: Lynch Mobs In La-La Land

Playwright and screenwriter Lillian Hellman called it “Scoundrel Time,” the name of her mid-1950s memoir of her experience with America’s 1940-1950s pandemic of anti-communist hysteria and witch hunting, especially her confrontation with the congressional House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Hellman, briefly a party member in the 1930s, was an “unfriendly witness” before the committee who declined to “name names” of former party comrades. She largely got away with it, perhaps because of her prominence and influential friends, but a great many others, in and out of Hollywood, didn’t get off so easily. Jay Roach’s Trumbo is about screenwriter Dalton Trumbo and the Hollywood 10, leftist writers who suffered greatly during the witch hunts and criminal prosecutions of those times. The 10 were all unfriendly witnesses before HUAC, refusing to say whether they’d ever been Communists, and trying to read statements espousing constitutionally protected rights over the gravel banging of Chairman J. Thomas Parnell (later a convicted felon). All were held in contempt and jailed. Director Billy Wilder’s much-repeated remark—“Only one of them was talented. The rest were just unfriendly”—may or may not have referred to Trumbo (under a necessary alias he wrote Roman Holiday), but it hardly reflected the critically serious nature of the era’s orgy of reckless accusatory agitation, bad faith, repression, and fear. My gosh, even I Love Lucy’s beloved star had to pay extorted money and publicly apologize because of her statements in support of free speech and some leftist skeletons in her closet. Lucy!

Trumbo makes an obvious effort to redress the historical ledger, but its success is, regretfully, only partial. To some extent, it’s self-handicapped. The movie is a combination of earnest striving for accuracy and honesty up against some muddled, fact-challenged recreations and too much drab narrative.

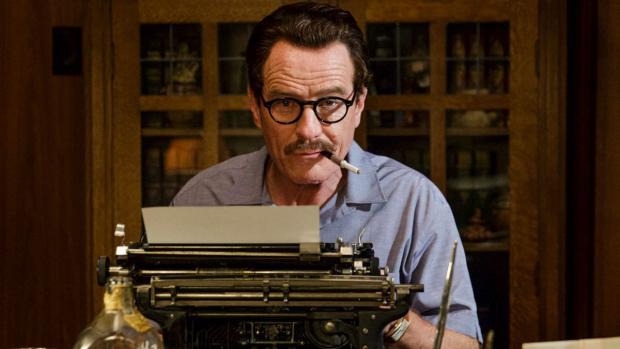

The movie opens in 1947 as Trumbo (Bryan Cranston) is at the apex of his success, signing a new beaut of a studio contract and living high on the Hollywood hog. But the storm clouds are gathering. The Hollywood right, led by such stalwarts as the draft-dodging John Wayne and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren in a broad, crude, ballsy impersonation) are out for blood, trying to have presumed reds and other leftists fired and jailed. Trumbo and his fellows caucus and plan their fight, financed in part by movie tough guy Edward G. Robinson (Michael Stuhlberg).

Much of the movie follows Trumbo’s post-prison career as a blacklisted, secret author of scripts for a producer of grindhouse schlock (John Goodman, freewheeling, funny, and typical), who doesn’t care if Trumbo was Joe Stalin’s boyfriend as long as he supplies scripts for his rubbishy movies. Eventually, Trumbo is vindicated and publically identified as the writer of major films (Exodus, Spartacus). In this telling, it’s director Otto Preminger, as much as or more than the widely credited Kirk Douglas, who helped end the blacklist.

A lot of this is reasonably well told and dramatized, but too much is bogged down in the domestic particulars of Trumbo’s threatened and damaged family life. His personal life is undermined, it seems, by the incessant need to pound out trash for a living. Maybe it really was, but the writing (by John McNamara) and direction are too pedestrian. Roach is not the director to goose or tart things up.

And, curiously, some of the film is historically questionable. Trumbo is the only one of the 10 to receive any treatment (the others aren’t even entirely named) and the movie produces a fictitious member of the group, Arlen Hird (Louis C.K.), as Trumbo’s skeptical and misfortunate pal. Roach and McNamara also unwisely make Robinson into a significantly treacherous, name-giving semi-heavy, an unwarrantedly exaggerated portrayal of the liberal stalwart and supporter of many of the same causes favored by the left.

Cranston is suitably amusing as the rakish, self-indulgent but courageous Trumbo and the movie has tackled a sharply pertinent history lesson and human story—I’ll skip over its contemporary relevance. One only wishes it was a little better.