Sara M. Zak at Canisius College

MISHAP contained

WORK BY SARA M. ZAK

Andrew L. Bouwhuis Library @ Canisius College

2001 Main St / Buffalo / website

Sara M. Zak’s artwork currently on show at Canisius College comprises complex but lucid and lovely paintings on woodcut blocks, and woodcut prints prior to the painting, about technology—which is complex but lucid ultimately—and bureaucracy—which often labors to be opaque.

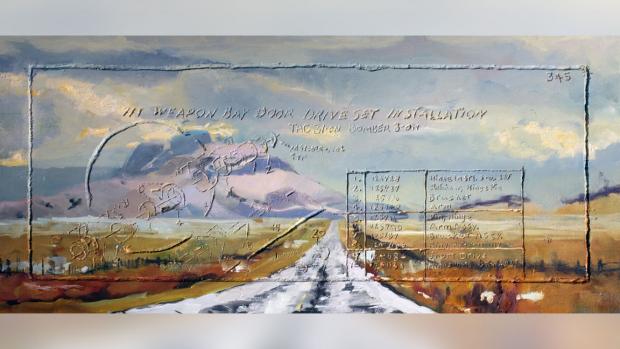

On one wall aerial-perspective landscape paintings of terrains ranging from spectacular—snow-capped mountain peaks, a chain of inland waters—to ordinary—what looks like scrub farmland, fields overgrown with small trees and brush—to nondescript—possibly a view over water, possibly at sundown, amid layered horizons of orange to red to golden fading daylight. That on closer inspection turn out to be on woodcuts, that is, on woodcut blocks line-carved with imagery that is hard decipher under the paint but is more clearly presented on the opposite wall in monotone blue prints—they look like ordinary blueprints, but with a deliberate hasty or preliminary work quality—taken from the woodcuts prior to the paint application. The woodcut imagery comprises technical drawings and data—as if from a maintenance or operator’s manual—on the F-111 Aardvark fighter and bomber jet that was used by the Air Force from the late 1960s through the 1990s.

The landscape paintings represent areas where an F-111 crashed in a training accident. The titles of the paintings are identification numbers of the plane that went down in the depicted area. Titles like 66-042. Locations are not designated. Whereas the titles of the woodcut prints are latitude and longitude coordinates of a crash location, plus the last names of the two airmen who died at that location. Titles like 36° 11’ 43.1” N 6° 08’ 35.5” W, Rudiger/Pitt. Whereas moreover the woodcut prints indicate nothing directly about the accidents, but merely present technical information on the airplane. But by matching up oil paintings with their mate woodcut prints—by deciphering enough of the woodcut carving under a painting to be able to match it to the print made from the same woodcut on the other wall—you can match depicted landscapes with latitude and longitude coordinates.

Not much information—and a rather roundabout way to get at it—but pretty much all the artist was able to discover when she tried to learn further details about these dual-fatal “mishaps,” as the military bureaucracy somewhat blandly describes them. Just what happened? Just what caused the crash and fatalities? Not information for public consumption. The implicit question the exhibit poses: Why not? No answer from the military.

One painting of a mountainous terrain is on a woodcut drawing of the fuselage and main structural components of an F-111, in a way that seems to show the plane on imminent crash course into the mountains. None of the other painting and woodcut image combinations is quite so dramatic. No connection between the woodcut images—mostly just airplane component parts or systems and technical data charts—and landscapes. Or landscape coordinates. Plus further minor disconnects in the photo-negative and reverse-image aspects of the blueprint imagery.

Art about disconnects and frustrations. Visually very beautiful—brushy impressionistic landscapes with underlay imagery, and handsome if hasty work woodcut prints—but verging on overcomplicated for the point it seems to be trying to make. Or what exactly is the point it is trying to make? That bureaucracy sucks? Political revolutions have overthrown governments, but not their associated bureaucracies. Bureaucracy is a little like the weather. Everybody complains about it, but what actually to do about it? One thing—this art project suggests—expose it. But an art project that seems to hover between complexity for the sake of depiction of a labyrinth and complexity for the sake of complexity. Very beautiful, but simplify, simplify.

The Sara M. Zak exhibit continues through November 27.