John Berryman's Shotgun

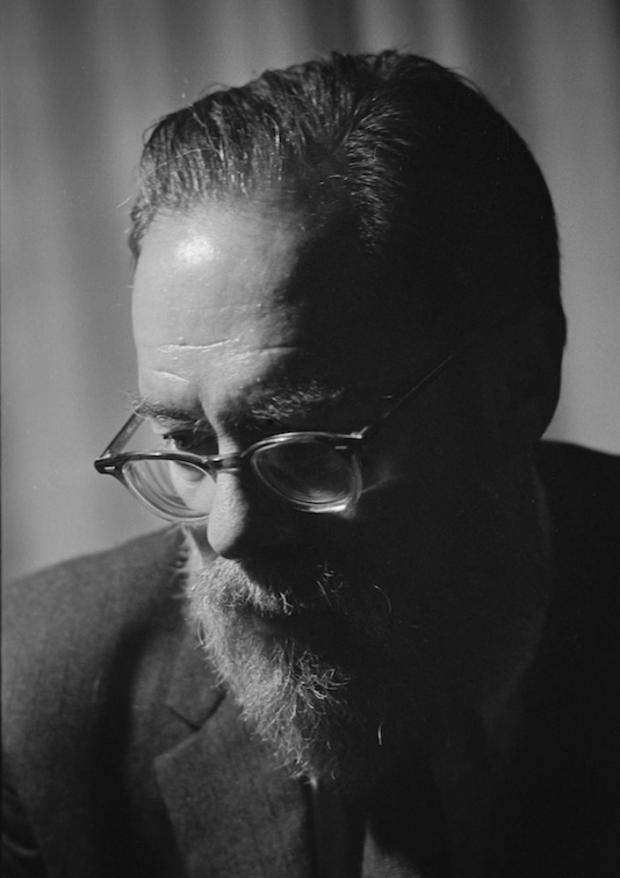

HBO’s recent mini-series, Olive Kitteridge, which starred Frances McDormand, Richard Jenkins, and Bill Murray, made frequent direct and indirect reference to the poet John Berryman, who committed suicide by jumping off a bridge in Minneapolis on January 7, 1972, into the cold waters of the Mississippi River. It even includes a line on a napkin over a bar from Berryman’s “Dream Song 235”: “Save us from shotguns & fathers’ suicides,” one of his books in a critical scene, and a shot of that book in the opening shot sequence for all four episodes.

Olive Kitteridge is full of people who consider suicide, who do or do not commit suicide, or who are the children of suicides. At the end Frances McDormand’s character is about to do it but doesn’t because some children come upon her (she’d earlier told another character considering it to think about the mess if children came upon his shotgunned body).

Berryman is now primarily known for his The Dream Songs (1969), a slimmer version of which, 77 Dream Songs, had been published in 1964 and won the 1965 Pulitzer Prize. One of the poems in it is about the suicide of Ernest Hemingway, who killed himself with a shotgun in Ketchum, Utah, on July 2, 1961. It begins, “My mother has your shotgun.” The later “Dream Song 255” refers to the poem’s protagonist shedding “tears in a dining room in Indiana that day.” I remember that. We were together that day.

I heard the first poem before it was published. I was a student that summer in the School of Letters at Indiana University, taking seminars with Berryman and Steven Marcus.

The first day of class, Berryman asked me, “Where can you get a drink around here?” It was a little before noon. The campus was dry so another student and I took him to a bar in downtown Bloomington. After a while, we had to leave. “I’m okay here,” he said. About six that night I got a call from a guy who said he was a bartender in that joint. “Will you please come and get your friend?” he said.

I asked him what he was talking about. “The guy you left here at noon. He’s had a dozen double martinis. I can’t serve him any more. Get him out of here, please.” I later found out Berryman had gotten my phone number from the class list.

So I drove down there and picked him up. I couldn’t bring him to the University hotel, where he was staying; they’d have thrown him out. So I brought him home. My wife was wearing a red, white, and blue outfit. It had no particular meaning; that was just what she happened to be wearing. We were coming up on Fourth of July Weekend, so for the next 12 hours he referred to her as “Miss American Flag.”

During those 12 hours he recited some of the “Dream Songs” he was then writing, a lot of Blake, and a lot of stuff I no longer remember. He told stories about his friends Saul Bellow and Alan Tate. At one point I started a tape recorder going and that tape is in the Library of Congress.

Throughout the six weeks of that School of Letters class we had several similar encounters. In the morning we’d talk about “Major and Minor Form in Poetry,” the subject of our class, which I never understood but thoroughly enjoyed, and then had boozy evenings in which John told stories and recited poems until nobody could stay awake any longer.

I was then sending a lot of stories and poems to magazines and accumulating nothing for it but rejection slips. I once said to him, “You don’t know what it’s like sending stuff out and it never gets published and nobody says anything.” He looked at me without sympathy and said, “You don’t know what it’s like when you send something out, it gets published, and still nobody says anything.” He subsequently got one of my poems published in The Noble Savage, co-edited by Bellow.

I was, that summer, working as a bartender and bouncer in a place called Nick’s English Hut. The bar had two constituencies. One was students and faculty from the University. The other was people from what we in the university called “the stonecutters,” people who worked in the limestone quarries surrounding the town. There was no communication between the two.

One night Berryman was in the bar with Steve Marcus and a few other people, and he began putting moves on a woman at a stonecutter table. From behind the bar, I could see the hostility rising. After a while, I went over and said, “John, she’s with a guy, you’ve got to stop.” He said he would, but he didn’t, and I saw the guys at the stonecutter table getting more and more pissed off.

Any bartender or musician knows what I’m talking about here; rooms have rhythms and you know when they’re going discordant.

Finally I went over said, “This table is flagged. Nothing more for anybody.” They didn’t argue that but Berryman kept making moves on the woman at the stonecutter table.

Every bouncer knows its far easier to prevent a fight than to break one up, so I came around the bar and picked Berryman up and carried him out to the street. He was a skinny guy and didn’t weigh very much. Steve Marcus pounded my back saying, “Put him down, you brute, don’t you know he’s a famous poet?” I said, “Don’t you know I’m saving his fucking life?” Marcus and I never got on after that. Berryman never remembered it.

At the end of that six-week seminar we had a party at our house. Around midnight, eight or 10 of us went out to one of the water-filled stone quarries outside of town—a place called the H-Hole—and swam. John disappeared. We had no idea how deep the quarries were; no one we knew had ever gotten to the bottom of this one. We called, but there was no answer. We dove, but it was dark and we couldn’t see anything. After a long time, when we decided we were in deep shit because we’d lost a major American poet, John called to us from a rock he’d been sitting on the entire time. He said it had been wonderful watching us jumping in the water, coming up for air, then plunging into the black water searching for him again.

We went back to our flat and the party continued for one more day. John and the sister of one of the students in the seminar disappeared for a while, then came in with blood leaking from the bridges of both their noses.

“What the hell?” I said.

“We thought we should do something to remember one another by,” John said, “so we bit each other on the nose.”

Not much to say after that, so people began to drift away and the party ended. The next morning was Sunday. John called and wondered if I’d meet him at the Indiana Memorial Union for brunch. I did. He was cold sober. He talked about the pleasure of clarity that comes with sobriety. It was as if the previous six weeks hadn’t happened. We had a lovely talk about current poets. Then he said, “I have one little problem.”

The problem was, the Union was dry, so he’d been dumping his empty bourbon bottles into a locked suitcase in his room, and now he was leaving, but he couldn’t find the key. He needed the suitcase to put his clothes and books in and he needed someone to carry out the empty bottles. Did I, perhaps, know a locksmith? And would I, perhaps, find a large bag….

I found a locksmith, we got the bottles out of the room and his clothes into his suitcase and he went back to Minnesota.

There was one other thing. He often referred to his good friend Robert Fitzgerald, who was my generation’s great translator of The Odyssey, The Iliad, and The Aeneid. The following summer I would have a seminar at Indiana with Fitzgerald on the Homeric poems, and the year after that, when Fitzgerald went to Harvard as Boylston Professor of Poetry and I went there as a Junior Fellow in the Society of Fellows we would frequently talk.

Berryman told me that Bob’s nagging problem was that he was a “lapsed Catholic.” That was a phrase I hadn’t heard before, so I asked him to explain it. “It’s a Catholic who no longer believes or practices, but who is uneasy about it, uncomfortable about it, who is displaced because of it.”

One time, when we were both settled in at Harvard, I mentioned that to Fitzgerald. He shook his head. “I have six children. It’s John who was the lapsed Catholic, not me. He was telling you about himself.”

Berryman often said that his “Dream Songs” were about a guy named in them as “Henry,” not about himself. After that conversation (and several of a similar nature) with Fitzgerald, I don’t believe it at all.

When John wrote, after Hemingway’s suicide, “My mother has your shotgun,” he was indeed thinking of his own father, who did himself in in such fashion. And he was thinking of himself, who would use another technique, but achieve the same end, only a few years later.

I was driving from New York to San Francisco that night in January 1972 when John Berryman jumped off that bridge into the Mississippi River. I’d been in Buffalo for a few days, seeing friends, then had gone down to the Bronx House of Detention for Men to interview Herbert X. Blyden, one of the key figures in the Attica uprising a few months earlier, for a magazine article.

(We would get to know one another and become friends 20 years later during the Attica prisoners’ civil rights trial in Buffalo. One day, Herbert said to Akil al-Jundi, the lead plaintiff in the case, “Brother Bruce and I been knowing each other a long time now. I was a young man then.” I said, “So was I. We’re the same age.” “I know that,” Herbert said.)

I was somewhere in Nebraska when the car radio picked up a newscast that said something about “the famous poet who jumped to his death in the Mississippi from a bridge in Minneapolis,” then faded. If you’re old enough, you remember how you’d lose AM stations driving across the country in those days, and how sometimes you’d get them back and sometimes you wouldn’t, and how FM stations only went so far and then were totally gone. It wasn’t until Nevada that I found a station with the report simple and direct.

I’d been pulled over by a Nevada state trooper for a bad taillight. We sat in his car talking for maybe 30 minutes while he ran a check on my car. After a while, I said, “Hasn’t that been taking a long time?” “Oh, the report on your car came in 20 minutes ago. You’re clear.” It was a cold winter night in the desert and he was just bored or lonely and wanted to talk with somebody. “You get that light fixed now,” He said. I said I would. I got back in my car and he u-turned and headed back up the road.

The car radio started picking up California stations. One of told me that the poet leaping from the bridge had indeed been John Berryman, and that a student crossing the bridge on foot was about a hundred yards away when he went over the rail and had reported it to the police.

The three people I’ve known who more than any others understood the nature of poetic voice were John Berryman, Robert Lowell, and Robert Creeley. That—finding the nature of voice—is what all art in any medium is finally about. If you find your voice, as they did, you can sing. Otherwise, it’s just noise. Berryman found his voice in The Dream Songs.