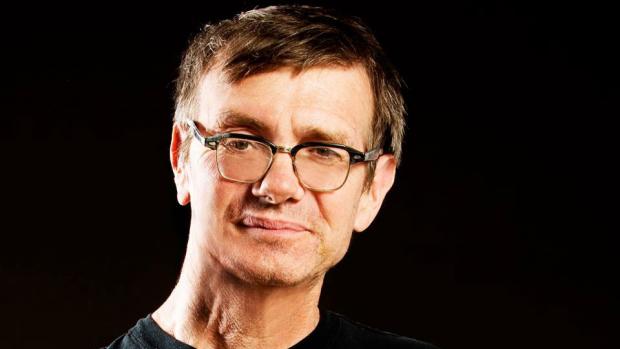

Storyteller as Plumber: An Interview with Kevin Kling

Kevin Kling was born with a short, malformed left arm, and over a decade ago he wrecked his motorcycle, suffered a brain injury, and lost the use of his right arm. Today, that right arm is often kept in a sling, and he wears a brace around his shrunken left hand.

I start with these observations because they are physically obvious and may seem of outsized importance when you meet Kling in person at Canisius College in November. And yet when I spoke to him they seemed almost tangential, only one of many influences to his craft.

Like famous fellow Minnesotan Garrison Keillor—“He’s so good at placing signposts ahead of himself, while at the same time leaving crumbs,” he said of Keillor’s ability to always end a tale where he started—Kling excels at the art of immersive Americana storytelling. He has recorded many such tales for National Public Radio, published the most well-worn stories in a series of books, and lately he travels the country, to festivals and stages and theaters.

During our sprawling interview, I kept resorting to telling my own stories as prologue for each question. I apologized, but Kling would have none of it. Listening to other people’s stories “is my favorite part of being a storyteller,” he said.

For those that don’t know you from NPR, how do you introduce your work?

I guess I’d start where I am, and most of my life now revolves around storytelling. I’ve gone through theater and writing books and children’s plays and play plays, and now I’m getting back to the grassroots nature of how and why we communicate, especially verbally, taking a story back to the oral tradition. I just got back from the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesboro, Tennessee. That’s the hotbed. It’s really ingrained in the people, and you can hear the most amazing story just sitting on a porch. But these festivals are all over the country.

What’s the difference between being a writer and a storyteller, if there is one?

There is a really big difference, in the way [the audience] receives the information. Coming from the page, it is a visual form, and when it comes from a storyteller, it is a visceral form, and you’re getting the inflection of the voice, the facial features. When you read a book the information is passed, but when someone tells you a story about throwing a ball, that part of your brain that you use when you throw a ball lights up, so an actual experience is passed through a personal story. After a storytelling the best thing you can hear is, “You’re almost as good as my grandpa.” That means you’ve connected, and that connection is the white hot of the moment.

Is this move from written to spoken word a function of your motorcycle accident, or do you think your artistic interests would have taken you in this direction anyway?

Even when I was writing books and plays I always wrote with a voice, and so storytelling now really feels natural. It feels like I was always doing this anyway. In college we used to say, “Your night before is only as good as your ability to tell about it.”

Has the storytelling job changed, with the rise of The Moth and podcasts and so much audio content?

It has transformed, but I’m standing somewhere in between the craft of the traditional method and the new method of The Moth, between the personal experience, and the shock and awe and the competition factor of so many of the slams these days. I’m really excited that it’s morphed, that we’ve put a stamp on an art form, and that’s really true to being an American. In most other countries, storytelling is still steeped in traditional forms, and yet you come to America and it’s all over the map. It reminds me of jazz.

How do you balance that, the jazz improv and the form of the traditional story arc that’s been around forever?

Jazz is about moving within certain structures, and even music follows a story form. When stories work they can be formulaic, but Nabokov said a story must entertain, teach and enchant. And I think the “enchant” is that part that you can’t really put your finger on. In Cajun cooking they call it the lagniappe, that little something something, that little ingredient that makes it all pop. A story needs that, something to get you to forget that it’s in a formula.

That’s why tonight I have a storytelling and I honestly don’t know what I’m going to say. I need to get in the room, see who is there, what has happened today, what does this place need, and I’ve got a few hundred stories I can tell, and I’ll just put them together and off I go. As a storyteller, you’re hardly ever in your own environment. You’re usually the visitor or the interloper. You need to establish a sense of trust, be vulnerable and use humor, and only then can you get into the deeper places.

Does the topic of the story really matter?

This is a great point. As time has gone on, I’ve learned there are no bad stories or wrong topics. The art of storytelling is place and time, telling the story in the right moment. I’ve always thought of stories as medicine, in that a story can help heal and can help kill. It can lead us in either direction, the same story.

You’re good at humor, but you’re not a stand-up comedian. Teach the rest of us how to do this.

Crack yourself up first, then your friends and family, then work your way out, in concentric circles. Once people close to me confirm its funny, I’ll put it in front of the unsuspecting public.

But if you tell stories for years, you must know where the laughs are coming. How often are you accidentally funny? People laugh and you don’t expect it?

A lot, and I like that actually, when it’s in an appropriate place. But when it’s somewhere that’s inappropriate, I’ll make a note and change it. I was recently in Thailand, and we were working on “A Christmas Carol,” totally forgetting that these guys were Buddhist. The story is about karma anyway, so it was going well. But there’s a scene near the end with Tiny Tim, and everyone started laughing. I kept saying, “This isn’t funny,” and they kept saying, “Oh, yes it is.” Finally, I gave in.

Sometimes, you’ve just got to let it go. After shows the audience will come up, and they’ll say what they saw or what they felt, and it might not have been your intent, but the last thing you want to do is pull away someone’s experience. The last thing you want to do is say, “No, that’s not what happened.” Because it did happen. The most important thing about storytelling is finding a connection with somebody. The reason stories ask the big questions—where we come from, before life and afterlife—is because we know these questions probably don’t have an answer, so we need to know that we’re not alone. Someone recognizing themselves in one of your stories is a coup.

Because I wrote a book about being in the military, everywhere I go I’m the veteran writer. Are you the disabled storyteller?

A moniker can either garner you an audience or shy them away. I hope that it still gets people in the door, because it helps me; as soon as somebody thinks they know who or what you are, then you’ve got ’em. You can either play into that, or go around it. The way I use [the disability] is that everyone knows loss. So how do we deal with that loss? That’s one of the reasons I use humor so much. If you can laugh at something it doesn’t control you anymore.

Is the disability part of your identity?

It is. When I got in my motorcycle accident, my storytelling really changed. It really focused it, gave me lots of new stories I could tell. It’s much more a blessing than a curse, that’s for sure. It also gave me a reason to be a storyteller. There’s a community element to it. I want to be as important as a plumber. To be a necessary part of the community, sometimes I need to be an entertainer, but sometimes I need to reflect back our values and our history, what our challenges are, what makes us unique.

The storyteller as plumber is about the most workmanlike, practical, blue-collar way one could view it, I think.

It is, but the word “playwright,” when you look at it, it’s not spelled like “writing.” It’s spelled like a wheelwright. You try to make a wheel true all the way around.

Catch Kevin Kling, part of the Contemporary Writers Series, Thursday, November 19, at 7pm at Montante Cultural Center at Canisius College.

Brian Castner is the author of The Long Walk and All the Ways We Kill and Die, which will be published in March.