At Buen Vivir: "If Voting Changed Things"

To enter the ¡Buen Vivir! Gallery for Contemporary Art and Orin Langelle’s new exhibit is to accept a challenge. Don’t expect a passive viewing of simple, aesthetically pleasing photography or a mindless stroll through apolitical eye candy. The challenge should be apparent from the title of the exhibit: It is a riddle, a fragment, an incomplete sentence awaiting your contribution. To view his display is to realize that there is no single way to finish the statement. Langelle invites you to see the complexity of the world through his lens, but to draw your own conclusions about the meaning of the images.

If Voting Changed Things… people would vote. They don’t. Only 58% of eligible voters did in the last presidential election. Recent polls indicate that the majority of Americans feel disenfranchised by the 2016 presidential election process and candidates. They aren’t proud or hopeful about the outcome, and half of Americans feel helpless. There is no emphasis on issues that matter to them. Election discussion centers around voting for the least worst candidate, which makes civic duty seem like an exercise in self-denial and a concession that our aspirations are not achievable.

Of course, the counter is that if you don’t vote, you’re giving someone else the power to make decisions for you. But that perspective ignores the range of opportunities for civic engagement and citizen action: Protesting, demonstrating, picketing, civil disobedience, rallies, striking, tax resistance, boycotting, sit-ins, sabotage, hacking and DDoS, tree-sitting, resistance, law-breaking, insurrection, rebellion, revolution. Langelle’s images of protest activity outside of national conventions in 1972 and 2004 raise the question of whether voting, and the electoral circus that accompanies it, is about citizen empowerment or an explicit and ceremonial abdication of power by citizens to a status quo elite. Which leads to the observation that…

If Voting Changed Things… they wouldn’t let us do it. Chomsky wrote that “The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum—even encourage the more critical and dissident views. That gives people the sense that there’s free thinking going on, while all the time the presuppositions of the system are being reinforced by the limits put on the range of debate.” Photographs from 1972 and 2004 capture moments outside of the system, beyond the framing of the acceptable discourse. Protesters explicitly reject governmental authority through symbols, slogans, caricatures, and artwork. The elephant pulling a coffin through Miami’s city streets conveys a belief that political parties are leading us to death and destruction. The black hoods and orange jump suits communicate that protesters in Boston, relegated to a “Free Speech Zone,” have become the equivalent of Guantanamo Bay detained terrorist suspects. It is not accidental that the media ignores or minimalizes these displays of collective action. In 2016 delegates—the people who were there (never mind viewers at home)—at the Republican and Democratic National Conventions remarked that they were unaware that protests were occurring outside throughout. Langelle deftly illustrates that this is because authorities have increasingly managed and marginalized protest behavior. Which demonstrates that…

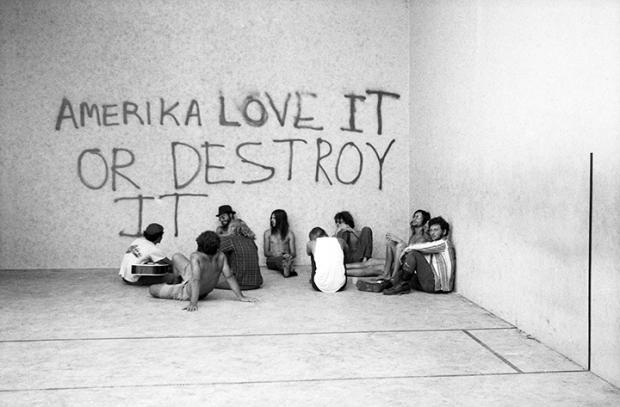

If Voting Changed Things… this exhibit wouldn’t be necessary. For many, Langelle’s work will be shocking because it lays bare the evolution of policing and the criminalization of dissent. Photos of the 1972 demonstrations include arson, sabotage, gratuitous nudity, and graffiti that challenges, “Amerika—Love it or Destroy it,” and yet not a single police officer is identifiable among the activists. The activists are in the streets, climbing in trees, occupying fields and grassy lawns, neighborhoods and parks. Contrast this with images of Boston Police in 2004, appearing ready for war in riot gear; armed with Tasers, guns, clubs; a menacing and ubiquitous presence atop scaffolding towers. Because of new draconian laws, protesters have been herded into holding pens of chain link fences and razor wire, surrounded by surveillance cameras, concrete, and girders. The photos depict a world that has changed drastically in thirty years, and which has militarized against, marginalized, and narrowly framed the acceptable boundaries of citizen dissent. Moreover…

If Voting Changed Things… it wouldn’t contrast so distinctly with other forms of citizen action. There is a humor and a vibrancy to “the people” that Langelle juxtaposes brilliantly against the sterile and colorless state apparatus. There is a diversity of skin color, age, gender among the protesters. Their slogans are racy, their clothing is colorful and fun. They wield musical instruments, engage in “guerilla theatre” and share poetry. They engage in property destruction with irony—wearing clogs as they break windows and asking through their graffitti with (gallows) humor if the protest restraint area represents the “Land of the Free?” Their defiance comes in the form of patches, to be worn on the derriere, sold by a young girl in a flowered dress. They paint their faces and wear straw hats.

The stark reality of the state is helmeted, with dark gray protective gear and weapons to enforce compliance. The only colors are the red, white, and blue banners and flags that appear more as a hypocritical challenge to the popular movements than a patriotic display. It is evident that Langelle sees a dour system that is oppressive and lifeless. Voting is a part of that system, a reinforcement of its values and an affirmation of the status quo.

If Voting Changed Things… marginalized groups wouldn’t be in the streets. The electoral process in America has produced and validated a government that has produced institutional racism, militarization within and from our society, mass incarceration, crippling debt, perpetual war, homelessness, a failed health care system, eroding and ineffective education, and environmental exploitation. If Voting Changed Things… we wouldn’t have a 1 percent. We wouldn’t allow the .01 percent, 16,000 Americans, to hold as much wealth ($9 trillion) as 80 percent of the nation’s population – some 256,000,000 people – and as much as 75 percent of the entire world’s population. We wouldn’t allow the five largest white landowners in America to own more agricultural land than all of black America. If Voting Changed Things… demographics wouldn’t be used as a basis for electoral strategies. We would vote away the cleavages that exist across generations, racial and cultural groups, religious affiliations. But we don’t, because we can’t.

If Voting Changed Things… would we be where we are? The work of Orin Langelle may offer you a lens from which to answer that question. Or to find your own conclusion to the sentence.

ARTIST TALK: ORIN LANGELLE

Friday, November 4, 7pm

¡Buen Vivir! Gallery for Contemporary Art

148 Elmwood Avenue, Buffalo, NY

Dave Reilly is professor and chair of political science and director of international studies at Niagara University in Lewiston, New York, where he serves as president of the faculty union and moderator for the Black Student Union.