The Grumpy Ghey: Like a Rock

I used to smoke crack.

Some of you already know. I’ve mentioned it here before, but the likely assumption is that I’m kidding around. Crack is funny to people—a signifier of low socio-economic status and bottom-basement desperation so extreme that we’ve made it into a parody. We use it to describe uncommonly delicious food, too. I’m not angered by that—it is what it is. Watching Cookie Monster attempt to freebase his cookie dough on Family Guy is hilarious. But, alas, I’m not kidding. In the 1990s, a good 10 years after crack ravaged New York, Miami, and Los Angeles, I became what we might call a second-generation crackhead.

So, how’d the kid from Scarsdale who had it all end up on the rock? It was just a series of coincidences. I’d been spending a lot of time hanging out at a bar where I’d previously worked as the sound and lights guy for the trash-drag shows they hosted on the weekends. It was a seedy place, but the no-frills atmosphere appealed to me. (I was never much for that rainbow-on-the-dance-floor, hands-in-the-air motif). Anyway, my sinuses had been bothering me due to all the powdered cocaine I’d been snorting. Late one night, after many drinks, I was complaining about this to a drag queen who suggested smoking the coke instead. After some cajoling, she explained how to do the chemistry. This was not the same as sprinkling some powder at the end of a cigarette.

Essentially, the kid from Scarsdale ended up a crackhead because anyone who smokes that stuff ends up a crackhead. Purified, freebased cocaine is not something which you casually imbibe and then wander off to the gallery opening. You get stuck. Right away. No turning back. First hit, you may get a little nauseous, but your dick gets hard. And from there, it’s all over. Mixed with the realization of an incredible high (which deteriorates quickly into herky-jerky paranoia) is a muted voice way in the back of your mind affirming that, indeed, “You’re in serious fucking trouble.” That Wikipedia has a “recreational use” entry on its crack cocaine page is beyond logic—there is no such thing.

I didn’t want to smoke crack and chat with you or listen to music. It wasn’t social. If we were smoking together, clothing came off and sex was all that mattered—save, perhaps, for the ever-dwindling supply of drugs, and making sure the pornography never stopped running.

But crack is clumsy. And flammable. It requires ashes from another source to burn properly in a homemade pipe, and the glass tube alternative fries your lips. Imagine: You’re shaking like a leaf from this intense overdose of stimulants (usually mixed with poppers), sweat pouring off your brow and fingers slippery with a putty of mixed lube and ashes (so sexy), attempting to load this valuable, oily pebble onto a bed of cigarette ashes in a shallow bowl. It’s a wonder I didn’t burn down any of the apartments that housed my addiction. I definitely put holes in sheets, carpets, rugs, underwear, couches, and chairs. And after a binge, there was always a grey, ashen film over everything in my world.

Have you seen those photos of Whitney Houston’s bathroom sink counter after a binge? Bobby Brown’s trashy sister sold them to the National Enquirer. I saved them. They’re a reminder of all the good stuff waiting for me should I ever decide to go back down that glorious road. And the only difference between Whitney’s addiction and my own was that I could never come up with enough money to make quite that big of a mess.

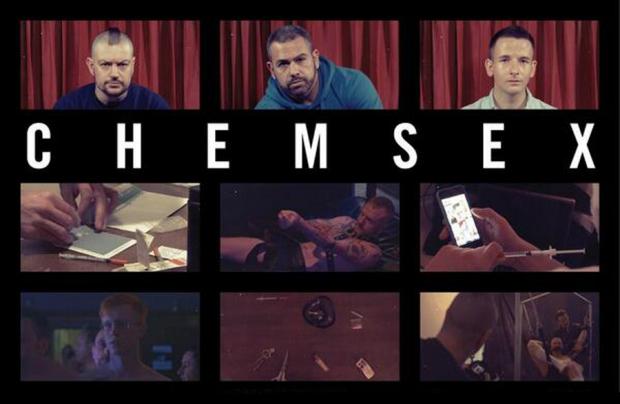

Somewhere toward the end of my journey with alcohol and drug abuse, now miraculously arrested for nearly 14 years, I was offered crystal meth to snort. I tried it a few times, but mixed with the buffet of whatever else had been consumed on those occasions, it didn’t register. My dalliance with crystal meth was fleeting, but a new documentary film, William Fairman and Max Gogarty’s Chemsex (Vice Films, 2015), out next month on DVD and available through multiple streaming services, highlights how my crack experience is very similar to what happens to gay men who get entangled with methamphetamine.

Meth is our new plague. It cannot be overstated. It almost seems like the drug has yet to achieve full impact here in Western New York, though I know a couple people locally who have struggled with it. It has been described to me as having all the desirable properties of crack, but it lasts infinitely longer and requires much less maintenance (fewer fire hazards). The highs have some slightly differing characteristics, but there’s one thing that definitely links them together: the fusion of drug use and sex.

Chemsex isn’t the first documentary to examine the relationship between gay men and meth, but it does so from a different angle than the others, looking at the phenomenon of chemsex itself. The term, which replaces the more euphemistic “party-n-play” (PNP), oft used on hookup sites, describes an orgiastic underworld of unimaginable sexual intensity. The film takes you into a private weekend party where meth is being used in conjunction with GHB (and its close chemical cousin, GBL), alternating between the ongoing scene there and the experiences of a few gay Londoners at various stages of addiction. The interviews for the film were done over the course of a year.

At the center of the story is David Stuart and 56 Dean, a London-based sexual health clinic. Stuart, who discloses his HIV+ status in the film and alludes to his own struggle with meth addiction, is the documentary’s voice of reason. His position at 56 Dean is that of a specialty chemsex counselor. He explains that the he’s the first sanctioned counselor of his kind within the UK’s public health system, and he’s since brought 56 Dean to international prominence as an authority on the chemsex epidemic.

“It’s about a gay community emerging from a rocky, traumatic past, a complicated past,” Stuart says of the trend. “We have vulnerable gay men with issues around sex, and when we add drugs which tap into that, combined with changing technology, it’s the perfect storm.”

When I got sober, it was difficult putting down the drink and giving up daily pot-smoking. But it was crack that called to me loudest in lonely, vulnerable moments. It was a bumpy nine-year ride from the first time I smoked it to the final binge, and lots of awful, demoralizing things happened to me along the way. Like the men in Chemsex, the thing that always dragged me back into the ring with crack cocaine was sexual desire. The two issues were forever entwined in my brain. Untangling them is a process that, frankly, may not ever be completely finished.

“Originally, sex and drugs were two separate things, but somewhere along the line, they became one in the same,” says one of the young men in the film. And several of them attest to the letdown of “dull” and “boring” sober sex after regularly engaging in comparatively limitless chemsex. Another subject describes the meth high as ”a fireworks display in your soul.”

Stuart asserts early on in the film that London’s meth problem is severe. He says young men logging onto the Grindr app will, on average, be invited to indulge in chemsex within four conversations—slamming meth intravenously within eight. For single men that use hookup apps, chemsex is becoming the norm in larger cities.

One of the film’s most disconcerting voices is that of fetish photographer Matt Spike, who we see doing a shoot in a leather dungeon. “I can’t help that the drug was ever invented,” he says, snapping photos of two men engaged in a sexual pose with a needle. “If that happens to look sexy, that’s not my fault.”

As an artist, Spike has every right to document the chemsex trend however he pleases, but his images are triggers, as is Chemsex itself. Meth addicts who have pulled themselves out of the drug dungeon would do best to steer clear of the film, which won’t tell them anything they don’t already know anyhow.

And yet, it’s a conversation we must be having, and Chemsex is an important film. One of the men in the film describes chem-crazed men as looking possessed, wild, hungry, and desperate. “I’m scared of this perversion of the gay scene,” he says. “It’s pathological; there’s something scary happening.”

Mixing sex and drugs isn’t new. It’s no secret that for many, sex is just “better” after smoking a joint. But this is extreme: intravenous use of a drug that’s known to cause permanent brain damage after only a few ingestions, coupled with sexual behaviors that mine the darkest depths of your imagination. There’s a clear descent involved, and many gay men are opting for a trip all the way down to the bottom.

Chemsex reminded me I’m lucky to be alive. But, hard as it is to admit, it also turned me on—further proof that once you open the door to the dungeon, it never completely shuts.