David Schirm at Hallwalls

You may have seen painting representations of early art galleries, from maybe the late 18th, early 19th century. Vast wall displays of wildly disparate works by artists of different times and locales and instincts—maybe no two works by the same artist—hung cheek by jowl, in multiple rows and layers, floor to ceiling. The current Hallwalls exhibit looks a little like that. Crowded walls of wildly various works in multiple rows and layers, floor to ceiling. Except in this case, all by the same artist, David Schirm. The exhibit is entitled All the Glad Variety.

Much of the work is about war, specifically the Vietnam War, in which the artist served as a combat engineer. And observed horrors that make it into the artworks sometimes in outsider art cartoons with proliferous tiny handwriting commentary or dialogue, sometimes in abstractions, as if in default of more literal representation of particular horrifics, or of the war in general. Other abstractions may or may not refer to the Vietnam war. Other works with substantial myth content in an eclectic variety. Buddha to Santa Claus. Other works encrusted with add-ons, from costume gems to what look like shards of broken glass, to little plastic soldiers or little plastic babies, sometimes impaled.

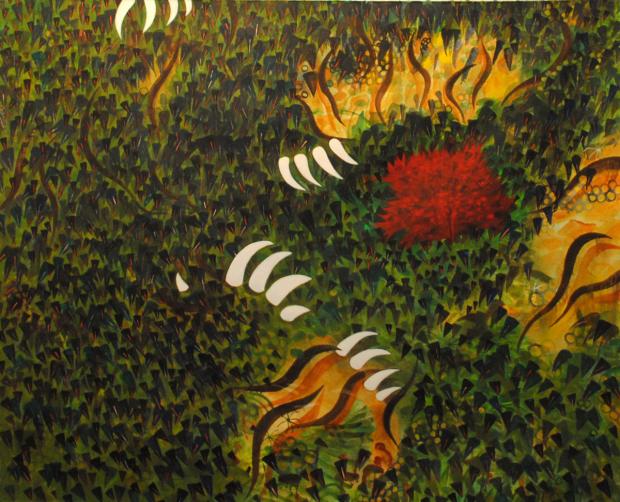

Some recurrent iconography amid the variety. Dome forms that regularly transmogrify—with the addition of two eye holes—into a niqaab Muslim woman’s headdress and veil, covering her entire face except her eyes. Other times transmogrify into solitary mysterious mountains. Also, circles, and dots, and bioforms—some add-ons that look like protozoa a million times enlarged—like something you might see in a science museum diorama about pond life—including floral forms that may be flame forms, may be fireworks, may be explosions. And lush greenery—gardens with the look and feel of jungle—and bombs, and bugs, and blood. And real fur. (You look around for a disclaimer that “no animals have been harmed in the making of this work.” You don’t see one.) And doodles of all sorts. In discourse in an accompanying booklet and catalog, the artist says he “made a conscious effort never to make the same mark twice in the same way.”

Along the way, he mentions a score or so of artists whose works he admires, and so presumably influenced his art. Artists such as Ben Shahn, Ad Reinhardt, Cy Twombley, Ed Ruscha, and Anselm Kieffer. And from the pantheon, Francisco Goya, Henri Matisse, and Charles Burchfield.

I was surprised he did not mention three artists whose work his works—as I perused them—frequently put me in mind of. Hieronymus Bosch, Henri Rousseau, and Mark Rothko.

I was gratified ultimately to see one of the paintings bearing the title Rousseau’s Blood. Amid thick jungle greenery—and here and there poking out of it, tooth and claw portions of tiger—a messy dark red patch. So much for pre-lapsarian peaceable kingdom romanticism. Not this artist’s world. Not the world of the Vietnam War. (Supposedly safe places that turn out to be dangerous is a kind of motif. A large format work called Tienes Cuidado de the Meadow depicts a peaceful landscape green meadow, suddenly overrun with little plastic soldiers.)

Hieronymus Bosch most notably in the largest format work in the show, and something of a centerpiece, based on its size, but also its portentous title, The History of the World—Pleasure and Pain, and its content. This is the work that includes both Buddha and Santa Claus. And any number of other myth figures and scenarios in an ultimately enigmatic amalgam that nonetheless does evoke the history of the world as the stories of gods and heroes—the term myth originally means story—and indeed of pleasure and pain.

Mark Rothko in some works of a numinous quality such that could cause a devout secular humanist to reconsider. Some of the mysterious mountain works, and other works such as He Is Dead, He Is Risen, consisting of a glowing red form that could be a three segments gothic church window ablaze in dawn or dusk bright sunlight, against a dark blue to black background.

Some 150 works in all, from over a four and a half decades span from 1972 to 2017, arranged for the most part without regard to date of production, or subject matter, or style, or any other perceptible ordering criterion.

We get variety. But what an observer also needs to understand about a body of work of a given artist is unity. Possible unities. How the body of work hangs together. How works of similar or related subject matter or style or theme change and develop over time. What these changes imply in terms of message or messages.

It is hard to see what is gained by the shotgun arrangement of the works, versus what may be lost, or harder to see, or impossible to see.

The David Schirm exhibit continues through November 3.