Bruce Jackson on Paul Strand at the Albright-Knox

Photographer, filmmaker, author, folklorist, and SUNY Distinguished Professor Bruce Jackson explores the photography and cinematography of Paul Strand at the Albright Knox Art Gallery tomorrow October 15, at 5:30pm. Jackson’s talk, “Paul Strand: Genius of Form and the Discovery,” is free to the public as part of a three-day program juxtaposing composer Aaron Copland and Paul Strand’s works inspired by Mexico.

“I’ve got 36 pages of single-spaced notes,” Jackson said during a recent conversation about Strand. “I’ve gotten obsessive.”

I made sure to come over early because “5:30 is martini time” in the Jackson-Christian household. We sat in the late-afternoon light at Jackson’s kitchen table framed by a floor-to-ceiling mosaic of art, photographs and books, circled by a pitbull and an impossibly fluffy white dog, while SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor Diane Christian and Jackson’s partner-in-crime relaxed in the living room.

If you’re a fan of Modernist photography and you know the way Jackson tells a story, you’re already anticipating this talk. But for those folks new to the genre, Strand, or Jackson, there may be laughter, tears, and talk of “Georgia O’Keeffe’s tits.” This will be your chance to get Jackson’s take on Strand, a photographer, filmmaker, and author born to Jewish parents in New York City roughly 40 years before Jackson was born Jewish in Brooklyn and went on to become a photographer, filmmaker, and author.

Why don’t we know Paul Strand very well?

Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Weston were a trio of people who made photography acceptable as art in America. Strand wasn’t as well known as the other two. In part because he came in and out of photography; in part because all his life he was a fanatic about printing. He just about never made more than two prints of one negative. Most of his negatives he never printed at all. And for most of his life, he never sold a picture for more than 200 bucks.

He didn’t like bright fluffy clouds. He called them Johnson & Johnson, like the cotton balls. He would take pictures on gray days, on days everybody else would go home. He was slow and methodical. I think you look at Weston’s nudes and Weston’s sand dunes that he shoots like nudes. They’re very dramatic. Strand’s pictures are quiet. Sometimes he would take a whole afternoon, up to four hours, to do one shot.

When Strand is taking early pictures of his wife’s bare shoulder, Stieglitz is taking pictures of Georgia O’Keeffe’s tits. His connections were subtle and suggestive. That’s the charm of his stuff to me. A small object is always a synecdoche for something larger. You don’t know what it is, but with art you don’t have to.

What did he photograph in New York at the start of his career?

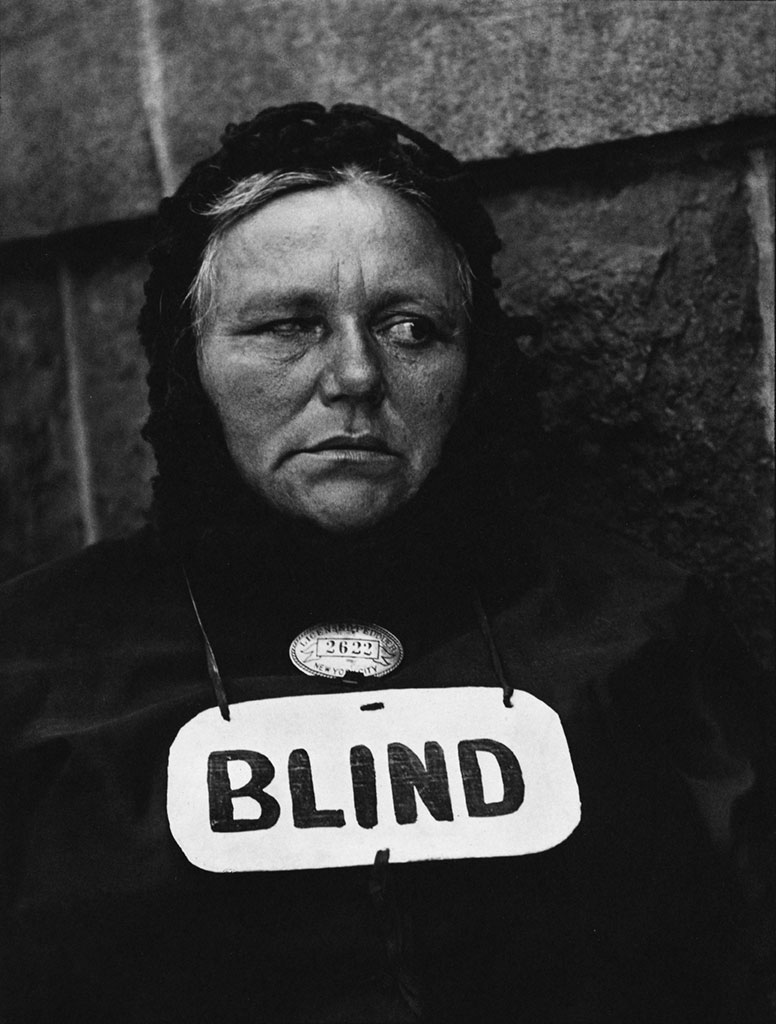

Strand does still photography starting in high school. Strand’s first teacher is Lewis Hine at the Ethical Culture School in New York. Hine helped Strand develop a social awareness that he had his entire life: He’s the guy whose photographs were responsible for child labor laws in America. Hine took the class to Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 and it was there that Strand saw photographs on a wall along with Picasso and Braque, because Stieglitz treated them as art all the same. He was the first person to do that. It blew Strand’s mind and he begins photographing seriously.

He started out with abstract photography—objects and how they related to each other in space. He threw that out and started making portraits. For a portrait to be successful, he said, it should make you feel like you know someone you’ve never met. The only unfocused portraits he made were his first. He snuck street portraits with a hidden lens stuck on the side of the camera. So, he often gets pictures in places he feels he can’t approach people. Nowadays we talk about the ethics of that but he said he never felt he was exploiting people; he was just trying to show their dignity.

Artists straddling the same time period often develop close, sometimes verging on emotionally or intellectually incestuous relationships which end up shaping each other’s works. How did this dynamic operate in Strand’s life before Mexico? I hope you’re not going to realize this question is actually a shameless request for 1930s art-world gossip.

Before he went to Mexico, Strand went to New Mexico. In New Mexico the group would be Strand, Strand’s first wife Rebecca Salsbury who was a painter, Georgia O’Keeffe, and the painter John Marin. These people were friends throughout their lives and all had an influence on one another. Georgia O’Keeffe had the hots for Strand before Stieglitz. She was with Stieglitz in an “art way” for five years before they got together, and Strand was around in New York during that time. She wrote a friend that Strand’s photographs astonished her, took her breath away. Later she said he was very influential in her painting.

If you look at the pictures of Rebecca in New Mexico you can really see the progress of their marriage. Early on, in New York, he took pictures of her that are very sensual close-up pictures. There’s one full torso nude from the neck to the thighs that is identified as a Strand. I’m not including it [in the photographs he will show at the talk] because I’m not convinced it is. Stieglitz took some pictures of Rebecca that were nudes, and this one is the kind Stieglitz was taking of Georgia O’Keeffe all the time. There’s one picture of Georgia O’Keeffe with her hands under her breasts, holding them up, looking up at him, and he’s got a similar picture of Rebecca doing the same thing. There’s something kinky going on there. But you don’t see any of Strand’s that are like that. What you see is a shoulder, a back, a hip, part of a face.

Then in New Mexico you start getting pictures of Rebecca in a doorway with a very dark background. There are a lot of doorways like that in his photographs. In other words, places where life goes on that you can’t get into. You know they’re there because you’re seeing them, but you’re not seeing anything. So, the Rebecca pictures become more and more severe. There are two of her fully clothed, dressed in black, and the way she’s looking at him, it’s like: You’re not getting laid tonight.

How did Mexico change Strand’s methodological approach as an artist?

Strand goes to Mexico in 1932 at the invitation of a Mexican composer friend. He was interested in Mexico because it had a revolution and he wanted to see the effects: Had people’s lives improved? Had it made a difference? He didn’t photograph in Mexico City. I think he felt it was in the towns and villages, not the big cities, where most of the effects of government were felt and where people had the least amount of ability to influence government. If you’re going to see what a government is doing, go take a look where it’s doing it.

Something happened to him in Mexico. I think he found his voice while in Mexico, and it was a filmic voice. It was also a belief that people who survived suffering had a dignity that should be honored and respected, and much of his work went on to show that.”

In Mexico his sense of socialism and his dislike of capitalism and mistrust of government intensifies. And his aesthetic sense changes. At first he takes photographs but then he makes the film Redes. “Redes” is translated in the American version as “waves,” but it really means “nets.” It’s about a revolt of Mexican fishermen against an exploitative manager. They’re trying to unionize. And after Strand made it, he won’t take any photographs for 10 years. He’ll be doing films and documentaries.

How does this experience of directing film shift Strand’s artistic trajectory?

After Mexico he starts making books, which is another way of achieving this idea of double voice he has as a filmmaker: going beyond discrete pictures of people to show images and words together. It wasn’t until his books started appearing that people realized how deep he went, that he was producing an enormous body of work that is enormously complex.

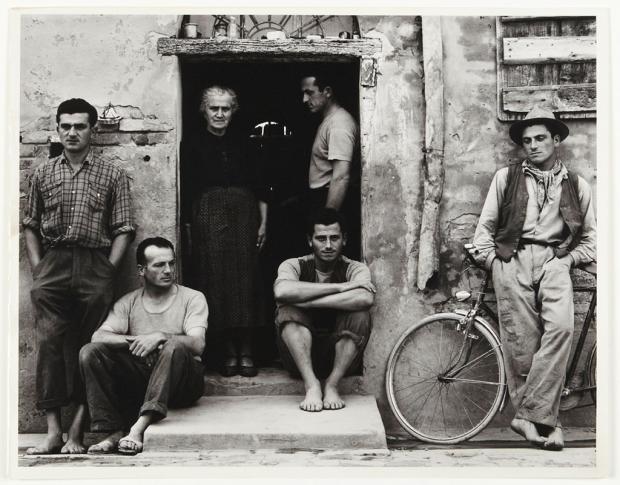

He meets the Italian Neo-Realist film-writer Cesare Zavattini and they do a book together in the town where Zavattini was born. He’ll do one on France, others on the Scottish Hebrides, Egypt, Ghana. He was invited to Ghana by Kwame Nkrumah at the behest of W. E. B. Dubois’s wife. He was interested in Ghana as a nation coming out of British domination and the 19th-century colonialist world, into the “modern” world.

He was directing in another way when he juxtaposed images in his books. Think about a gallery show. In a show, whatever object you’re looking at, there’s an object to the left and right of it. As you move you see a different configuration every time because of your peripherals. You may see a nude here, a nude here, and a shotgun here, and you get one feeling. You move over and you have a shotgun here, a nude here, and a shotgun here—totally different feeling not occasioned by the picture itself but by the juxtaposition. So in a way, going through a gallery is like your own movie.

I see—and I guess everyone makes his or her own movie because people walk differently. But in a photography book, where the peripherals are fixed, Strand controlled the context and showed the reader her or his own movie. It’s surprising to think of Strand as being so directive when his photographs seem like unstudied social documents.

Strand said, “All art is abstract.” All photographs are abstract because they are a two-dimensional representation of a four-dimensional world. A photograph seizes time but, as photographer Gary Winogrand said, “A photograph is not the thing photographed: It is something else.” Strand was acutely aware of that. There’s a famous photograph Strand took out of a courtroom window in lower Manhattan of figures in a park across the street. He said in an interview with The New Yorker: “There were three men. There should have been two. I took the third guy out in the dark-room.”

For him, fiction could be just as much a part of portraying reality as straight reality could. Aristotle, in Poetics, said that poetry is closer to the truth than non-poetry. In a lot of his portraits Strand would move people to stand against a different building than where he found them. He wasn’t just the photographer, he was the director. He was creating these complex objects that weren’t just photographs with captions.

People think of a photograph as an isolated moment in a subject’s life. But Strand’s “complex objects”went beyond moments to represent whole stories, whole lives. How did Strand’s own story end?

He leaves the country for France in 1950 because he didn’t like what was happening here politically. I think he worried that they might come after him. It later turned out that the FBI had maintained a file on him for decades. They’d been watching him all the time.

His very last work had no people in it at all. He moved to Orgeval, a village 20 miles outside of Paris. He got his first darkroom there. All his life he never had his own, he was always going to clubs and using other people’s.

So the last thing he does is two collections of photographs. He knew he was dying of cancer. One is a selection of photographs from his entire career: an 11-photograph portfolio. The other is six photographs from the garden that looked at pattern: the relationship of a leaf to a rock. He could no longer print but Michael Hoffman, who was responsible for the publication of most of his books, convinced him to let another photographer print for him during the last years of his life.

His last words, his three last words, were: “All my books.” [Jackson stops and his eyes fill with tears. He regains control and laughs.] If I say that in the talk, I hope what’s happened just now doesn’t happen. It wasn’t “my photographs.” It was “All my books.”