Bruce Beyer Reflects on 50 Years of Activism

In 1966, having been thrown out of a private military academy, I barely graduated from Bennett High School. My father insisted I attend college and I resentfully spent a year at a junior college before I unceremoniously failed out.

During the summer of 1967 I worked as a night clerk at the Imperial 400 Motel at Main/Summer Streets. It was eventful summer. I was robbed at gunpoint, stumbled on a friend of my parents who was cheating on his wife, became friends with jazz legend Jimmy Smith, and witnessed the police and media response when rebellion broke out on Buffalo’s East Side.

Because of its proximity to the East Side, journalists from across the country made the motel their base. Buffalo police used the parking lot as a staging area as they planned forays into the streets. For two days it was like sitting beside a battlefield watching. I began to make connections to the Vietnam war.

I knew my school failures would lead to being drafted and my scant knowledge of the war made it sound uninviting. In an effort to avoid ground combat, I enlisted in the Air Force on a delayed entry basis. I read about Vietnam. I drew parallels between the war and racial injustice but military service loomed large in the horizon.

In late August of 1967 I met a woman involved with anti war activities. When she heard my plan to enlist she asked if I had ever considered just saying “NO”. I had never heard of such a concept nor had I considered it. Two days later I made the decision to attend an anti-war demonstration in Washington and turn in my draft card.

On October 20, 1967 I stood on the steps of the Justice Department and returned my draft card to then US Attorney General Ramsey Clark. This act symbolized for me my opposition to the war and my desire to throw off what I came to describe as my “whites skin privileges.” By this time I came to realize that minorities and white working-class young people were serving while those of us from middle-class backgrounds were allowed an escape through a system of deferments. I would disavow my privileges. If it took going to jail as a way of serving my country then I was prepared to go.

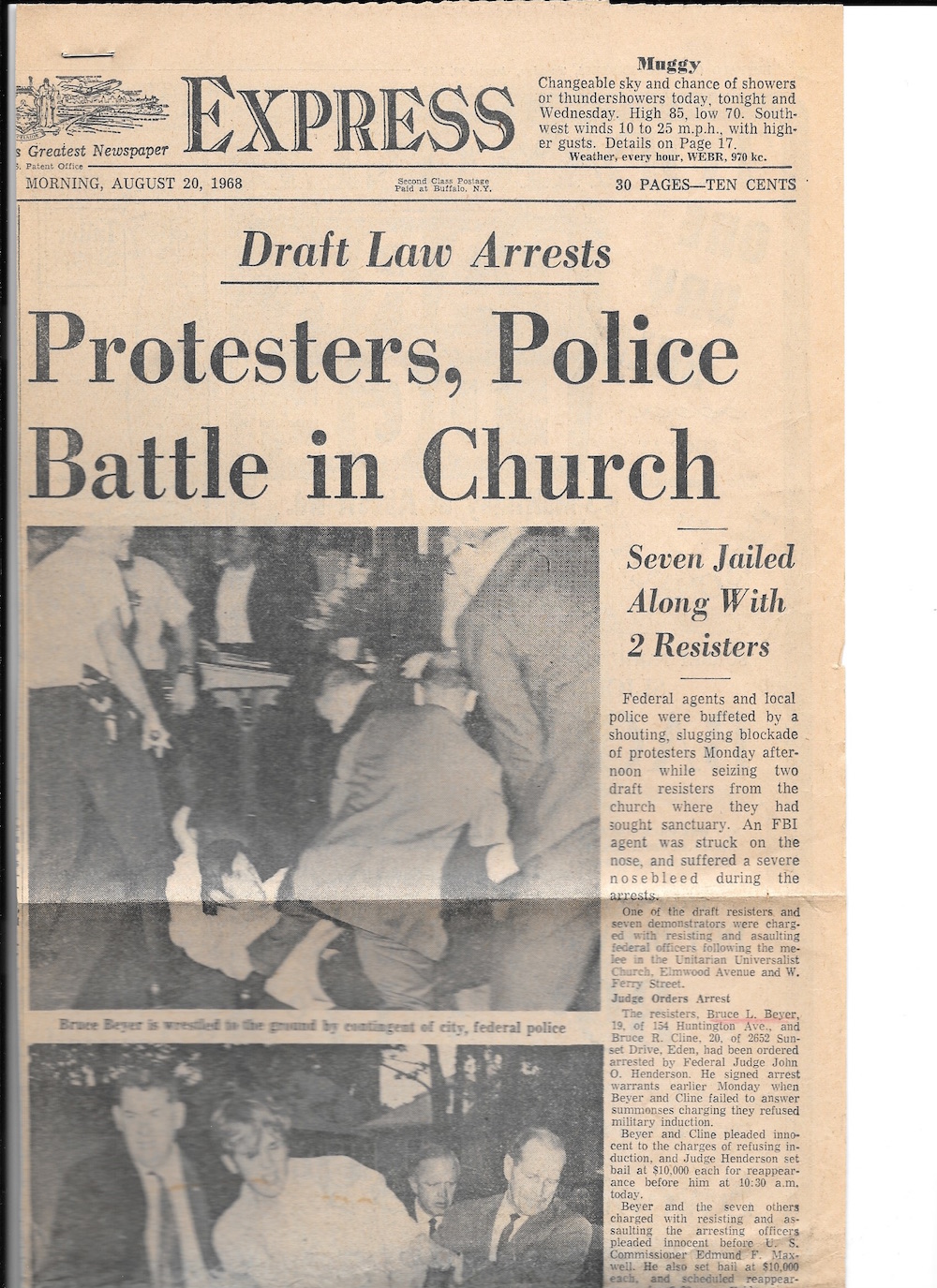

Over the course of the next 10 months, I received three orders to report for induction. I publicly refused each time. Upon receipt of the third order, my friend Bruce Cline and I took symbolic sanctuary in my family church. After 10 days, 32 FBI agents and federal marshals, backed up by 100 Buffalo police officers, arrived at the church doors demanding my surrender. I refused.

Over the course of the next 10 months, I received three orders to report for induction. I publicly refused each time. Upon receipt of the third order, my friend Bruce Cline and I took symbolic sanctuary in my family church. After 10 days, 32 FBI agents and federal marshals, backed up by 100 Buffalo police officers, arrived at the church doors demanding my surrender. I refused.

What started out as a nonviolent protest against the war in Southeast Asia ended in a fist-swinging melee. I and eight of my friends were charged with assaulting federal officers in the process of carrying out their official duties. Of the nine of us arrested, four were veterans. William Yates, at age 16, lied about his age and enlisted in the Navy during World War II. He fought as a ground combatant in the Pacific. Ray Malak, Tom O’Connell, and Jim McGlynn all served in Vietnam.

There were two Buffalo Nine trials. At the end of the first one, I alone stood convicted. At the end of the second trial, Yates and Malak were found guilty. They had refused to stand when Judge John Henderson entered the courtroom. When ordered to do so, Raymond said to the judge, “You don’t stand for us, I won’t stand for you!” Yates and Malak were immediately hauled off to jail for 30 days for contempt of court.

In 1969, having been convicted for the assault charges, I was out on bail and awaiting trial for having refused induction. My opposition to the war grew more vocal as the body count on both sides rose to staggering proportions. I spoke out at every opportunity I was given. I gave a speech at University of Buffalo after which students destroyed the ROTC offices located in the Clarke Gym. I was charged with inciting a riot, arson, burglary, and conspiracy to incite a riot.

Now facing considerable jail time, I jumped bail and fled the United States. After six months of hiding in Canada, I eventually made my way to Sweden, where I was granted humanitarian asylum. Two years latter I married my Canadian girlfriend and we immigrated to Canada. I lived in Canada for almost five years and began the process of applying for Canadian citizenship.

In the Spring of 1977, a friend gave me a copy of a book entitled Winners and Losers by New York Times foreign correspondent Gloria Emerson. Reading her book changed my life. I realized that in order for me to resolve my life, I needed to return to my homeland whatever the consequences.

My parents were getting older, my country was being told to “put the war behind us” by both Presidents Ford and Carter. I decided to come back publicly. I wanted to challenge the notion that the war was over. A government simply cannot engage in the mass murder of over three million people, sacrifice almost 60,000 of its young citizens in the process, and then tell people to put it all behind them. How many billions of dollars were wasted? Perhaps we should have donated the money we spent on waging war? Instead our leadership choose to defoliate Vietnam with Agent Orange and spread cluster bombs across Laos and Cambodia. This cannot be forgotten.

In making the decision to return to the US, I searched for legal advice. The draft refusal charges against me had been dismissed by the US Supreme Court. The New York State riot-inciting charges had been dropped. I was facing three years in prison for the assault charges and the possibility of bail-jumping charges were extant.

Friends in the movement for universal unconditional amnesty suggested I contact former US Attorney General Ramsey Clark. I knew that he had been to Ha Noi shortly after leaving office, I knew that he had spoken out strongly against continuation of the war both in private to President Johnson and vociferously upon returning to public life. I phoned him in New York City and he responded, “Bruce, I’m the one who got you into this, I owe you the chance to resolve it.”

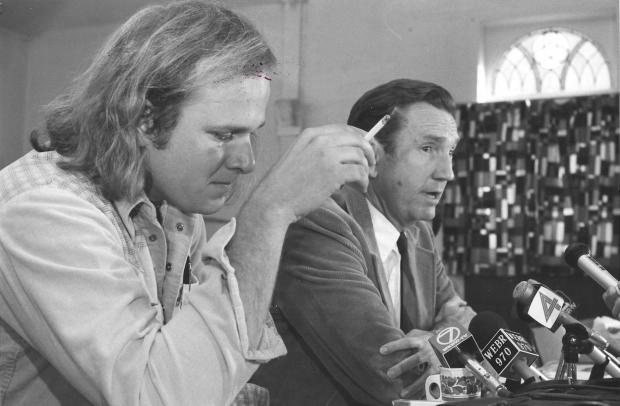

A week latter Mr. Clark flew to Toronto. We sat and got to know each other, talked legal strategy, and philosophy. I took an instant liking to him and when he flew back to New York City that afternoon my resolve to return to the US was strengthened. I sent out a press release to the Courier Express and the Buffalo Evening News informing them of my intention to return home. Both newspapers carried the story and a columnist at the Courier Express, Michael Healy, wrote a piece entitled “War Protester to Face Music As Sounds of Grim Era Echo.”

On October 20, 1977, I came home. Literally holding my hand as we crossed the Peace Bridge was Colonel Ed Miller, the highest-ranking Marine Corp ex-POW, who had spent five years in a Ha Noi prison camps. Ramsey Clark held my other hand. Gold Star mother Patricia Simon, author Gloria Emerson, my father and 50 mostly Vietnam veterans made up the contingent of walkers. I was arrested at customs, transported to the federal building, and brought before Judge Curtin. He took us into his chambers, looked at the US Attorney, then to Mr. Clark, and turning to me said, “Mr. Beyer, I’m going to let you go home. I’m not going to require you to post bail and I expect you will present yourself in court when required to do so.”

I waited a year for Judge Curtin to reach his decision regarding my incarceration There were infrequent conversations with Ramsey Clark and I was reminded of how I felt after I turned in my draft card and waited for the FBI to come arrest me. In the end, he reduced my sentence from three years to 30 days. I was given “credit” for the 19 days I had already served in 1970. I spent 11 days at the Erie County Correctional Facility.

October 20, 2017. Fifty years since the day I returned my draft card and 40 since I came home. To commemorate this event, my wife Mary and I planned to drive to Washington, DC so that we could stand on the steps of the Justice Department and simply remember. Then I received a phone call from a man organizing the Vietnam Peace Commemorative Committee asking if I would be willing to be a speaker at the Pentagon. Without hesitation I said yes.

I’m going to Washington to remember, but more importantly now I am going to Washington to point to the past 50 years and ask, “Have we learned nothing?”

The president of these United States is threatening war against another small Southeast Asian country. We already murdered more than a million Korean people in the 1950s and we sacrificed more than 33,000 young American lives doing it. Are we going to continue to walk down this unending road to war?

We have not even begun to atone for the genocide committed against Native peoples when we invaded their lands. We have yet to pay reparations for hundreds of thousands of African Americans dragged here in chains and forced into slavery. Long dormant bombs and anti-personnel devices continue to kill across SE Asia. Agent Orange persists affecting the lives of unborn children.

When will we ever learn?

Bruce Beyer lives in Western New York with his wife, Mary.