The Real Arts Economy: Place-Making, Not Tourism

Thanks to the brand-new data release from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, measuring the economic impact of the arts in shrinking Rust Belt metros is an easy chore. We know the numbers of people who work in performing arts and museums, we know the approximate dollar value of the money everybody spends on arts-related activities, and we know that arts and culture mainly happen within regional economies.

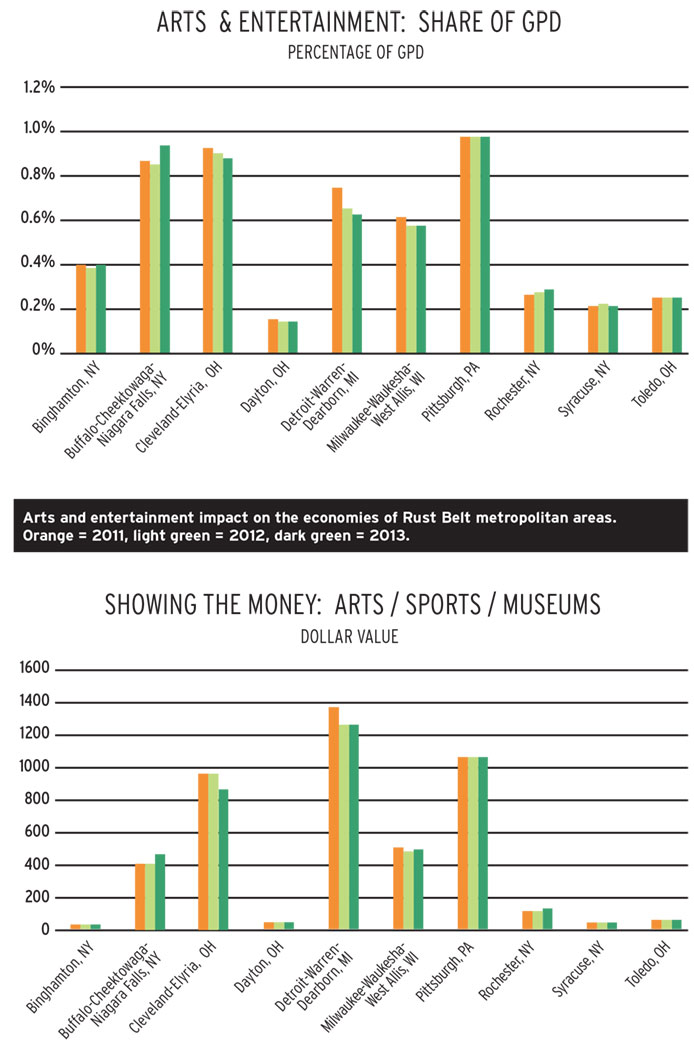

And the news is good: Since the financial crash of 2008, arts and culture are recovering along with the rest of the economy. Arts and culture as a share of the overall economy here in Buffalo are doing really well. The sector is doing well pretty much everywhere in the Rust Belt—and has an outsize economic impact in the smaller metros that don’t have the distraction of money-exporting major league sports.

Because live music, live dance, locally produced visual art, and locally produced sculpture, pottery, metalwork, and other such products tend to be purchased locally, the dollars involved flow through the local economy and remain “sticky,” getting spent here rather than exported.

And because producing art and cultural objects and experiences tends to happen close to central business districts, the very presence of arts organizations and individual artists helps maintain the locational “virtuous cycle” that the Rust Belt so badly needs—namely, to counteract the apparently permanently empowered sprawl machine that continually sends people, firms, their dollars, and their building permits farther and farther away from downtown.

If only the accumulated economic impact of the sector known as “performing arts, spectator sports, museums, and related activities” amounted to more money. In the Buffalo-Niagara Falls metro in 2013, where our total gross domestic product was a whopping $49.5 billion in 2013, the sector accounted for $457 million of economic activity. In other words, including the Bills, the Sabres, the Bisons, the Bandits, and college sports, the total impact was just under one percent of the total economy.

The numbers that roar

Republican presidential candidates may live in that fantasy world where cutting taxes and cutting public investment produce magical Pegasus-unicorn gifts for everybody, but here in the real world the ongoing investment of Erie County tax revenue in this sector keeps the wheels turning. The dollars that flow back into local government are greater than those that get invested in the first place. The last time anybody did a complete job of parsing the numbers, they went something like this: Erie County’s annual investment of $6 million in arts organizations and museums returned $14.9 million, because the 3.4 million attendees spent an average of $20 apiece. Sales taxes alone saw the outflow replaced by the inflow—but then there is all the other revenue that comes from all the associated activity that happens around the entertainment process. Folks who go to concerts pay for parking, meals, drinks, tips, merchandise, and babysitters, plus the cost of getting dressed up to go out, the cost of getting to the performance or gallery space, and more. Folks who work as performers, producers, servers, managers, and in the myriad support roles live here, consume here, pay rent here, invest here. The money stays and the tax revenue flows. If the sector were smaller, and all our tax dollars were purchasing for us were subsidies for the itinerant football and hockey mercenaries who live elsewhere, the economic impact of public investment would be far smaller.

The other reality that these numbers show is this: The gross domestic product of Buffalo-Niagara Falls metro has grown substantially since 2006, the last year for which we have the input-output analysis for arts and culture for Erie County. Inflation has not been very much of a factor, but nevertheless Erie County hasn’t raised the $6 million annual investment in the arts, either, even after the current county administration’s predecessor not only interfered with the process but also cut the annual investment. The overall economic output in real, inflation-adjusted dollars has recovered since the crash of 2008. It’s about time to undertake another economic impact analysis—because the size of the input matters. And it’s difficult to differentiate which part of the overall impact is from the large increases in the prices that the pro sports teams charge versus what’s actually happening on the cultural side.

That’s why it’s interesting to compare Buffalo with smaller-market Rust Belt towns that don’t have big pro sports operations.

Rochester, New York and Toledo, Ohio both show that performing arts, spectator sports, and museums account for 0.3 percent of their GDP. Rochester is about the same size as Buffalo-Niagara Falls, Toledo much smaller. Neither have pro sports other than minor league baseball and hockey teams. They both have “legacy” culturals, including well-regarded museums, and they both have “innovation” arts, namely very strong and varied music scenes, including festivals, and current practitioners in visual arts. They both have universities that are significant presences. The total dollar value of Rochester’s sector: $176 million in 2013. All told, the economic impact estimate for Buffalo in 2006 was $155 million. The total impact today is probably somewhere around $200 million, with the rest of the number attributable to professional sports.

Place-making

These numbers used to be produced to justify the ongoing public investment in the arts organizations that hire a few thousand people; in Buffalo-Niagara Falls, it’s about 5,000 people out of around 600,000 total workers in two counties. Then came the intellectual phenomenon known as Richard Florida, and his two-word epiphany and star-machine achievement: “creative class.”

Having the arts around might just mean that the “creative class” will flock to your town and make your town rich again. That was the explicit promise of Florida’s insight—and it earned him lots of consulting gigs and speaking engagements.

For a while, lots of other policy professionals—especially consultants who do input-output analysis—got lots of work producing reports like the one that Americans for the Arts produced for Buffalo. One of the best-known was by the National Governors’ Association, which came out of their “best practices” policy shop a few years ago. The arts and cultural organizations were seen as immensely powerful tools for economic development.

Then the economists started checking things out. Ann Markusen from the Hubert Humphrey public policy center did a little reality check about the actual intake of new dollars, tourists, and new industries, and found what our own experience here has shown us: namely, that tourist attractions may bring a trickle of newcomers, and that artists are great to have around because they liven things up, but that it’s pretty implausible to believe that they’re going to make “common cause with other members of Florida’s ‘creative class’, such as scientists, engineers, managers, and lawyers.”

Markusen has since gone on to be a consultant herself. She produced a very sensible piece of work for an organization of mayors of medium-sized cities. The report is called “creative place-making.”

It sounds about right.

There’s no reason to complain that the arts are not pulling their weight in the Rust Belt. Let’s not fret overmuch about an economic sector that employs fewer than one percent of the workforce and contributes less than one percent of the overall economic output.

But let’s not starve it, either, out of some notion that it’s okay to subsidize professional sports because of its economic benefit. Sports dollars stay local when the sports are college, minor-league, or amateur, but mainly dollars follow players. In the arts, the players are local. The dollars stay local. So let’s recommit ourselves to buying, supporting, attending, and best of all being local. It’s the economically sensible thing to do.

Bruce Fisher is a visiting porfessor at SUNY Buffalo State and director of the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.