On the Mark: Arrowhead Spring Vineyards

The upfront investment for a winery is staggering. It was requires native rootstock and vinifera to graft to it. Then it takes three years to get fruit from the vines, and that fruit must be aged, which requires barrels, a place to store them and more time. For Duncan Ross, this was a lifelong dream; Robin Ross, while willing to try anything, needed a bit more convincing.

“Robin and Duncan had bought the land,” says James Susice, head of sales at Arrowhead Spring Vineyards. “Robin wanted to move out to the country. It was always Duncan’s dream to open a winery. To prove that he was able to make good wine, she made him enter a competition and prove his worth. Either way, the land was already bought and it was a matter of whether they were going to just live out there or dedicate lots of resources to starting a winery.

“So he enters the competition and then they move and forget about it. What is now the vineyard was all brush, so they were focused on clearing it. They built the house. There was a lot going on—it was furthest from their minds. Then this giant package from the Indiana State Fair comes in the middle of winter and they are, like, ‘What is this?’ Then they pull a trophy out for Winemaker of the Year.”

At the time, the Indiana State Fair was the largest amateur winemaker contest in the country.

Where to begin?

The Rosses purchased the land on the Niagara Escarpment just west of Lockport in 2004. The prior owners had done nothing with it. It was covered in brush. Not a farmhouse. Not a barn. Not even a gravel driveway. But the thick brush growth was evidence that the soil was healthy. Standing outside, looking over the rows of vines in front of me, offers a stark reminder of the impact people have on their environment, even the friendly farming practices at Arrowhead Spring Vineyards.

In 2016 the Rosses purchased an additional 23 acres a half-mile away from the current property. “The newer land we just bought has been farmed more recently so it comes with more issues,” Robin Ross says. ”Soil depletion, et cetera. Crops were sprayed, and of course that is an extremely common occurrence, and that spray, at least what is allowed in the US, breaks down after a couple of years. And another problem when people spray, and what people don’t consider, is that when you use pesticides and herbicides, you then don’t get that layer of weeds and things on the soil. Those plants help keep nutrients in the soil and also help break things down. Otherwise the crop plants just take everything and it takes time for the soil to recover. What we need to do is put down a layer of organic manure on it, then the following year put a cover crop on it, and then I feel like it is on it’s way to recovery.”

Robin Ross’s role is growing operations and horticulture. Duncan Ross is in charge of the company’s vision and winemaking. Robin has plans on selling their grapes to more people in the industry. Many winemakers don’t grow the grapes they use to make the wine. “Usually the winemaker and the grape-grower are separate entities. They are just very different businesses,” she says.

Goldilocks

Currently, Arrowhead Spring Vineyards grows merlot, cabernet sauvignon, chardonnay, pinot noir, syrah, tempranillo, riesling, vidal blanc, and cabernet franc. Cabernet sauvignon is the third most planted, pinot noir is second, and cabernet franc is number one. “It grows beautifully here,” Robin Ross says. “It doesn’t have as many issues with our climate, and it also makes a great red wine for us. I’m very happy with how it turns out. In 2006, when we first planted, we planted cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, chardonnay, merlot, syrah, and malbec. We got good fruit from the malbec grapes for a couple of years, but we also noticed that it had diseased leafs, so it wouldn’t last forever. One difference between people and plants is that plant diseases are degenerative. We get better, plants don’t. We know it wouldn’t last, and 2010 was the last time we had a vintage.”

Though Arrowhead Spring Vineyards is only a 35-minute drive from Buffalo, the proximity to Lake Ontario has profound effects on growing conditions. “We find that several varietals grow really well here,” Robin Ross says. “With the lake being 10 miles away, we have our own micro-climate. It heats things. Lake Ontario is 30 miles across and 600 feet deep, which is why that lake doesn’t freeze. From a weather standpoint, it keeps our winters slightly warmer, which is why you’ll find vinifera that can grow here that can’t grow in other places that have a similar summer climate, like Minnesota. Also, because the lake is such a thermal sink, it keeps things a bit cooler in the spring, delaying bud break till after the frost danger has passed. That’s why you see two belts of fruit growth in Niagara County: right along the lake, and then right across the escarpment.”

How to grow

Currently you can find conventional, sustainable, bio-dynamic, and organic wines in most stores. In the beginning, Robin Ross, who describes herself as an “armchair environmentalist”—figured that organic was the way to go. Upon doing a bit more research, she had become disillusioned. “Organic is great concept, of course, but to think that is totally free of sprays, for example, is false. Organically certified sprays are used. One of the organic sprays contains copper, and copper isn’t good for soil. It sounds wonderful, and people generally look at it as being cleaner than traditional farming, but traditional farming can be very clean as long as farmers are sensitive to what they are applying, when and where. Agriculture, on the whole, is doing a better job now than they ever have when it comes to sprays. For one thing, it is very expensive, so why do it more than you need to? We are sustainable, which puts us somewhere in the middle, and gives us the advantage of using the best practices of each on a scale that makes sense for us.”

For me, strolling through the vineyard, sloping down from the tasting room and house, is relaxing. Then again, I don’t work there. Robin Ross walks through with eyes darting to and fro. Suddenly she points up, competing to be heard against the wind: “One thing you’ll notice is that we don’t have a perfect canopy. There are some holes in our leaves. They are from Japanese beetles. I don’t spray if I can avoid it, so we let them do a certain amount of damage. Leaves can still photosynthesize even if they don’t look as pretty.”

We turn and go down a row of cabernet sauvignon. She gets down on one knee and motions for me to do the same. “We don’t use herbicides anywhere on the farm. In a lot of vineyards, you’ll see the area near the roots being a bare strip with no grasses or plants. What I personally don’t like about that is that in order to have healthy soil, you have to have plant life. Those plants die and break down, and they add nitrogen, et cetera, back into the soil. Those plants allow microbes and bacteria and tiny insects to run around in the soil, keeping it aerated and light and fluffy. I just don’t see the logic in having a dead zone where you want a plant’s roots to develop. Sure, there is competition for water, but when you have an overdeveloped canopy and nothing near the roots, you can get a vegetal taste in the wine.

“I love seeing that,” she says, pointing to a plant near the roots. “That is a wild sweet pea, and when that dies and breaks down, it’ll add a lot of nitrogen back into the soil.”

The Wines

There is no reason to go all the way to a vineyard and not leave with a few bottles. Thanks to Michael Chelus of the Nittany Epicurean for allowing The Public to share his tasting notes for some of my personal favorites.

2013 Unoaked Chardonnay: This wine is 100 percent chardonnay from the Niagara Escarpment. Following alcoholic fermentation, the wine was aged sur lie in stainless steel ,where it underwent malolactic fermentation. It comes in at 12.5 percent ABV. The wines showed a pale straw color. Tart apple, lemon, slate, hay, and whiffs of stone fruit all arrived on the nose, with the stone fruit becoming more perceptible as the wine opened up. Granny Smith apple, lemon, hay, slate, and hints of stone fruit followed on the palate. The wine exhibited good acidity and minerality, along with good structure and length. This wine would be a great aperitif on a hot afternoon and would pair well with steamed clams.

2013 Cool Terroir: Each year, the blend for this wine consists of varying proportions of syrah, merlot, cabernet franc, and cabernet sauvignon. Each wine is vinted and oak aged for 12-24 months separately. The wine is then back-blended to arrive at the specific percentages unique for each vintage. It comes in at 15 percent ABV. The wine showed a dark ruby color. Blackberry, cassis, white pepper, mossy earth, and oak were each discernible on the nose. Blackberry, cassis, white pepper, current, mossy earth, eucalyptus, and oak followed on the palate where the wine showed a more earthy side than its 2012 predecessor. The wine exhibited good structure and length, along with moderate tannins. This wine would pair well with a wild mushroom risotto or a grilled flank steak.

2012 Meritage Reserve: This wine is a tradition meritage blend of 100 percent estate grown fruit: 40 percent merlot, 34 percent cabernet franc, and 26 percent cabernet sauvignon. Following fermentation, the wine was aged for 12 months in French oak barrels. It comes in at 13.5 percent ABV. The wine showed a dark ruby color. Blackberry, cassis, violet, eucalyptus, oak, and mossy earth could all be found on the nose where the earthen notes supported the berry. Blackberry, cassis, licorice, mocha oak, and eucalyptus followed on the palate with the mocha emerging as the wine opened up. The wine exhibited great structure and length. Quite tannic, this wine could be cellared five to eight years. This wine would pair very well with a seared dry-aged ribeye steak or braised lamb shank.

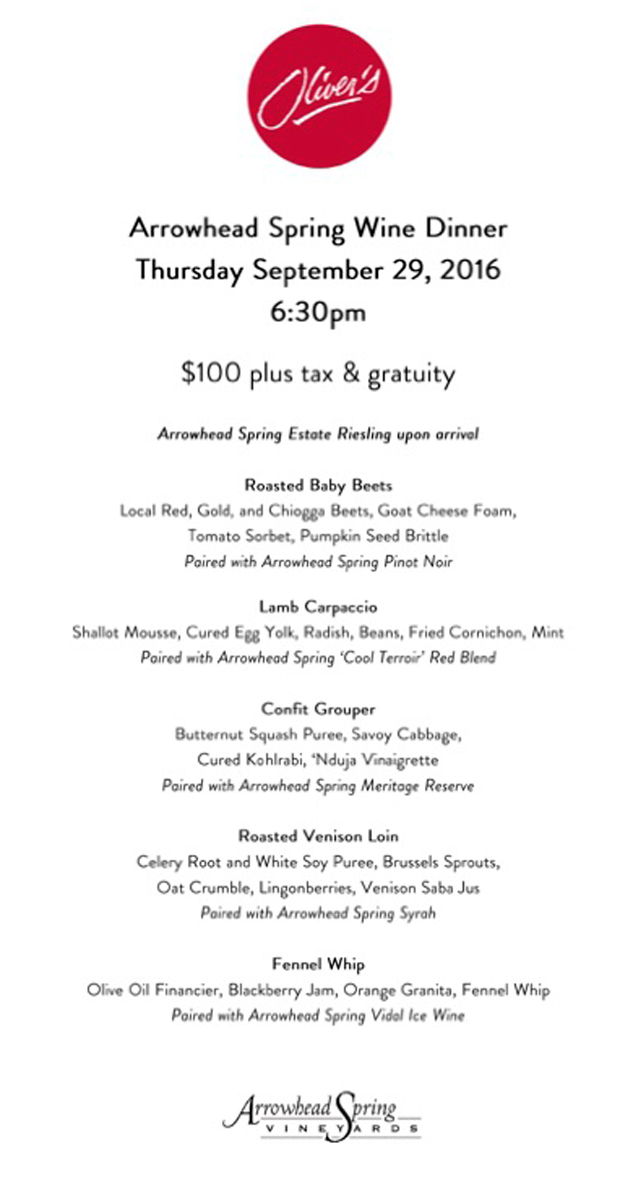

Join the Nittany Epicurean for an Arrowhead Spring Wine Dinner at Oliver’s this Thursday, September 29, 6:30pm: five course, accompanying Arrowhead Spring wines, $100 plus tax and gratuity. Menu below: