A New Convention Center: The $500 Million Question

You’ve been invited by Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz to add your voice to the conversation about whether Erie County should spend $500 million on a new convention center. Let’s hope that thousands of citizens rush to the public comment website where they can present their fact-based, well-reasoned analysis of the question: Should taxpayers spend $500 million on a proven economic loser?

It’s not a loser because critics say so: Just read the consultants’ own report.

Consultants hired by Erie County delivered their report last week, in which they insist—despite the numbers that they helpfully include—that spending between $480 and $520 million would create as many as 200 jobs, or $2.5 million per job. In the Buffalo metro area, there are around 550,000 people with jobs, so the 200 jobs would be an increase of a seasonal rounding error.

The consultants also calculate that the new $500 million building would have a net annual impact of an additional $34 million a year in the Buffalo-Niagara Falls metro area’s $50 billion regional economy—an increase of just under seven-tenths of one percent.

Revenue from operating a new convention center that is twice the size of the existing one would be approximately double today’s take, say the consultants, even though the new place would also operate at an annual loss of between $1 million and 2 million. But in order for the 200 new jobs (not at the convention center itself, but in the area) and the new money to happen, the hotel industry would have to increase by at least 1,000 the number of available beds in a market where today about 30 percent of hotel beds are empty. The consultants essentially state that there would be a huge (epic, unprecedented, fantastic) increase in the number of visitors to Buffalo who would come here expressly and specifically for the purpose of utilizing the new convention center. (It is not clear how many of the 200 jobs would come from an expansion of the hotel industry.)

If you believe that local elected officials are interested in making policy decision based on data, and not the way they usually make decisions (i.e., saying yes to the real-estate developers who give politicians here most of their most campaign money) then please read the report here, and pay particular attention to the following data points:

- The current convention center is a break-even operation thanks to the $1.7 million or so in Erie County bed tax revenue that covers the annual operating loss. The proposed new convention center would also lose money, with the loss subsidized by county revenues.

- National trends in attendance at conventions are inconsistent, with no growth for several years, but one out of five with professional meeting planners predict growth—mainly in training, education, and sales events. (That means that four out of five professional meeting planners do not predict growth.)

- Only 14 percent of the reason why event planners don’t choose Buffalo, according to the report, is because the current convention center is too small. “Event planners indicate that overall destination appeal is the primary reason for not hosting at the BNCC for approximately 37 percent of lost events,” the consultants say. Further: “Ongoing improvements to downtown Buffalo and its tourism-related amenities and other destination improvements would improve Buffalo’s potential in the market.”

- Let us return to that point this way: The proposed new convention center would be about twice as big as the current place, and the consultants project that that increase in available space would in itself stimulate demand for use of the space—even though the consultants state that most of the decision-making about whether to come to Buffalo is not based on the size of the convention center.

- Just under half of the events “lost” by the current convention center are conventions, which are events held by and for out-of-towners; the other events that don’t use the place are events of, by, and for local people: banquets, meetings, consumer shows, trade shows, sports events, and “other.” This means that more than half of the local events go to other venues, of which there is no shortage here.

There are more data points, which we will get to. But we’ve been through this before.

In 2001, when a full Environmental Impact Statement was prepared for the proposed convention center that the Buffalo Niagara Partnership insisted was absolutely necessary, the conclusion was pretty clear: Building the new convention center would cost $250 million, but the net economic impact of the new structure would be negative, and that we were better off keeping the old one.

How the decision will be made, actually

The numbers again: $500 million for 200 jobs.

New York State taxpayers spent $750 million on the Tesla plant in South Buffalo, a plant that currently employs 600 at an average wage reported to be north of $60,000. Tesla has pledged to employ 1,400 within two years and 5,000 within five years.

New York State spent the money, owns the building, and lets Tesla use it in return for employing local people in manufacturing in an area that has lost 45,000 manufacturing jobs since 1990. So the state had a specific goal (to bring back high-wage manufacturing jobs), a specific target (5,000 jobs within five years), and a yardstick: to create a $30 million annual payroll that would otherwise have been created someplace else. The total economic impact of that $30 million payroll would be anywhere from $60 million to $100 million, depending on a slough of factors that economists calculate using a generally accepted software package that addresses about 100 factors in what’s called “input-output analysis.”

So if the state investment works out, then each of the 5,000 jobs will have cost $150,000 in 2017 dollars. If Tesla under-delivers, then each of the 1,000 jobs will have cost $750,000. And although the delivery and installation of solar roofing-tiles has been slow, the business press generally regards the Tesla plant in Buffalo as the real deal. But in the worst-case scenario, should Elon Musk and his firm have to move out, then New York taxpayers will still own a big building that some other high-tech manufacturer could use to build solar roofing-tiles, LEDs, and the other stuff that currently keeps 600 people making average wages of $60,000 apiece.

The average wage in the hospitality industry, for example, in serving clients of the convention center, is currently under $12 an hour, and not full-time, and without benefits such as health insurance, pension, or sick leave.

But this is how capitalism seems to work now: Big industrial firms still get major subsidies for delivering tech jobs that pay decently. Old-style make-work subsidies for sports stadiums, convention centers, and amenity upgrades at public venues are very much the old way, the Old Normal in New York State, but there has been some recognition in Albany that New York has to compete with Sun Belt states that bribe industrial firms very, very effectively, so maybe the day of the Old Normal is done.

The convention center question now before us is this: Will the Old Normal return?

Focusing on the numbers

New York State may well not be in any position to keep doing what it usually does, which is to send the Buffalo area about $1 billion more in state revenue than the Buffalo area sends to Albany—because of the Trump tax bill. That bill ended the deductibility of state and local income taxes, and changed the way Medicaid is reimbursed. And as Trump is still in office with a Republican majority in the House and in the Senate, some governmentalist nerds wonder if a potential federal government shutdown could be engineered to injure the Blue states, especially California and New York. Others wonder if the Republican majorities and the Republican President could wreak havoc with more changes before January, when, if it eventuates, a Blue Wave would be seated in Washington.

Meanwhile, the discussion of the Buffalo convention center feels like a zombie reprise of the 1990s, when supine local politicians allowed us to be bullied into a long, expensive, distracting conversation about whether to replace what was then a 20-year-old convention center.

Here is the most important number, then as now: zero.

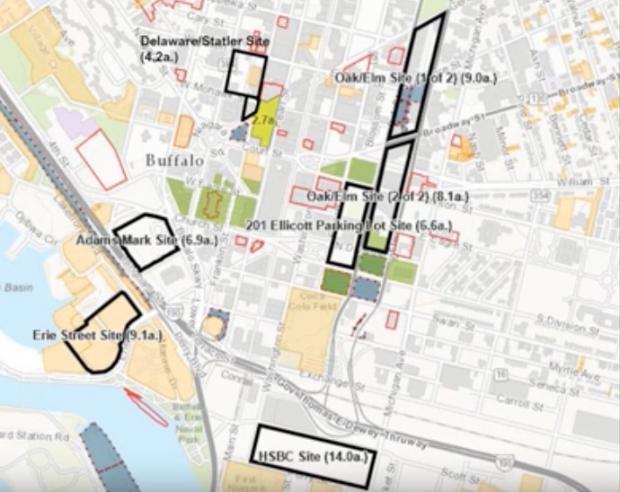

That is the chance that a new convention center—either at the Canalside site or on the block that currently houses some offices, some restaurants, a charter school, and a local performance artist’s Tuesday fried-dough enterprise—would not require a massive New York State subsidy.

The consultant’s report has a most intriguing figure: local tax revenue from the proposed new convention center would be less than the annual operating deficit. In other words, the annual deficit today of between $1.5 million and $2 million is smoothed by using county revenues. The annual deficit of the new place would need the same subsidy—except in the first several years of operation, when the deficit is projected to be much greater than in the “normal” years down the road. Revenues from the larger operation, and from all the new hotel rooms, would top out at under $1.4 million.

What we have now

The existing convention center is busy over 200 days a year, mainly with events that serve the local market. The few actual large-scale meetings are mainly held there by New York State organizations that rotate between Manhattan and Rochester, Syracuse, Albany, and Saratoga, all of which have big meeting spaces and amenities for visitors. The occasional national or international groups (always welcome!) are small and infrequent. Important growth in revenue in recent years has come from amateur sports.

But there’s more.

One of the proposed sites is next to Pegulaville, and the Pegulas have voiced a desire to have a new convention center next to their sports, hotel, working, and beer, donut, and fried-food complex.

The argument is that Buffalo can’t be “competitive” without a new, bigger place, and that such a place should be next to the new icons of our Renaissance.

A handful of huge destinations—New York City, Las Vegas, Orlando, Chicago, Los Angeles, and some amenity-rich places like Washington DC, Toronto, Montreal, Nashville, and San Francisco—get the big meetings. That’s where the actual conventions go, leaving medium-sized cities like Buffalo to scrape along with regional meetings of medical associations, statewide teachers’ unions, boat and car and home-repair shows, and a few bargain-hunting small-time affinity groups that can’t afford the Javits Center, McCormick Place, or the immense behavioral and bacteriological risks posed by Las Vegas professionals.

So when the guy from the Buffalo-area automobile dealers’ association says that he wishes he had more space to show his cars during the annual two-week Auto Show, he’s saying that he wants Erie County taxpayers to take 100 years’ worth of all the money we currently invest in the Zoo, the Philharmonic, the Science Museum, the Botanical Gardens, 19 theaters and about 50 other cultural organizations that the County funds annually to make life here nice.

Or we could just get the State of New York to buy him a virtual-reality headset for each of his hot prospects.

Or we could pop some popcorn, and sit back, and wait for the usual rent-seekers (the economist term for people who bribe politicians in order to get public money) to trot out their fantastic promises, and then order drinks as the usual bobble-heads from academia and the private sector agree that Buffalo can only be “competitive” if we have a new convention center.

Last fact: In 1996, two economists from the University of Pennsylvania predicted that Erie County’s population would be 909,000 in 2020. The Census estimates that Erie County’s population will be 925,000 in 2020. The Penn economists in 1996 didn’t estimate that approximately 20,000 refugees would accumulate in Buffalo over the past two decades; otherwise, their estimate of our population was spot-on.

In all that time, we had a convention center. Our population in 1980, a couple of years after the convention center opened, was 1.01 million. In 2000, it was 949,494. It would seem that the existence or non-existence of the convention center would mean about the same.

Bruce Fisher teaches at SUNY Buffalo State and is director of the Center for Economic and Policy Studies. His latest book, Where the Streets Are Paved With Rust: Essays From America’s Broken Heartland (The Public Books/Foundling Press 2018) is available at Talking Leaves Books and at foundlingspress.com.