"White Only"

Last Wednesday (September 16), Ashley Powell, a UB Art Department graduate student, posted 17 signs—all on white cardboard, some saying “White Only” and some saying “Black Only”—near campus water fountains, elevators, toilets, and other places.

It was a public art project, a class assignment, what these days is called an “intervention.”

Within an hour, university police started receiving calls about the signs. Some students later said they were frightened by the signs, some thought they were an act of terrorism, some said there should have been a campus alert sent out.

The event was the subject of several articles in the print and web versions of the student newspaper; it made the New York Times on Monday; it was the subject of a contentious meeting of the Black Student Union at which Powell defended her work before other students, many of whom were outraged by it.

In a long letter to The Spectrum, Powell wrote:

I understand that the ambiguity of the “black only” and “white only” signs are problematic in light of recent events on other campuses where actual acts of hatred, misogyny, and racism occurred. However, my work is something else—an artistic intervention. This was not a social experiment. I do not need to experiment with non-white people’s trauma, nor pain, to know that is there. This was not a joke. I do not need to, and will never joke about my own reality, or anyone else’s, because our reality is grave, it is frightening, and it is one of constant endurance, resilience, and burden. This project, specifically, was a piece created to expose white privilege. Our society still actively maintains racist structures that benefit one group of people, and oppress another. Forty to fifty years ago, these structures were visibly apparent and physically graspable through the existence of signs that looked exactly like the signs I put up. Today these signs may no longer exist, but the system that they once reinforced still does. Any white person who would walk past these signs without ripping them down, shows a disturbing compliance with this system. These signs do not allow a white person to give the age old excuse of “I didn’t create this system” or “I never asked for this white privilege.” They attempt to give those people the individual agency to rebut the very system that puts them in a place of supremacy. These signs illustrate that white people do not have to be active aggressors, like the KKK, to be responsible for this system of racism and white privilege that threatens, traumatizes, brutalizes, stunts, and literally kills non-white people every day in the United States.

She also wrote, “I apologize for the extreme trauma, fear, and actual hurt and pain these signs brought about. I apologize if you were hurt, but I do not apologize for what I did.”

It is a good letter and warrants a look. The whole letter is online at The Spectrum website.

She’s right. If the signs were that offensive, why did the campus police have to cover the campus, finding them and ripping them down? Why didn’t everyone else do it? Her signs, and the older signs they evoked, are about a basic fact of American life: Nearly every person of color at some point, or at many points, confronts racism. She invented those signs; she did not invent their subject.

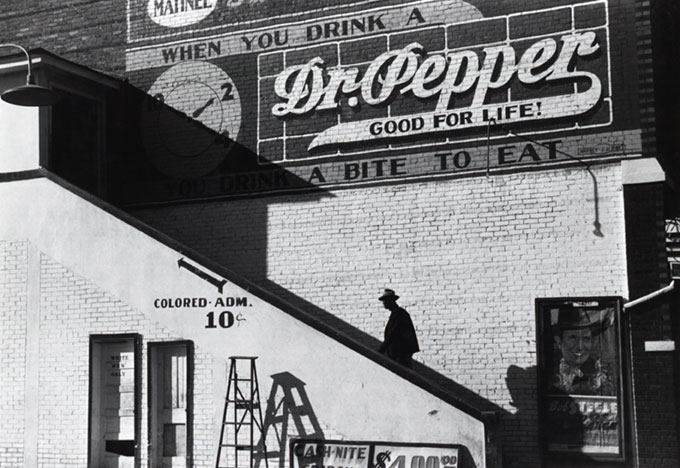

Marion Post Walcott, movie theater, Belzoni, Mississippi, 1939.

Marion Post Walcott, movie theater, Belzoni, Mississippi, 1939.

In 194 years, outside of New York City, only one black male and two black women have been elected to New York State Supreme Court. According to The Guardian, blacks are twice as likely as whites to be shot by police, even though they comprise only 13 percent of the population. You cannot have read a newspaper, listened to or watched a newscast, or been on social media without learning of the huge income disparity in the United States, the huge number of people of color in prisons, the overwhelming fact of white privilege. A week ago, a raving lunatic said to the Republican leading candidate that the major problem of this country was “those Muslims.” The lunatic said they had training bases for terrorism in this country. Donald Trump touched his comb-over and responded, “That is one of the things we will look into.” Not one of the presidential candidates called him out for that.

Not only did some people on campus go ballistic about Powell’s project, but so did Buffalo News art reviewer Colin Dabkowski, who, in a venomous attack article headlined, “UB art student’s racial provocation adds to trauma,” went on at length about what a violation of everything this was, and how the artist’s letter to the editor was self-serving and rambling.

It was neither. The Spectrum had asked her to comment on what she did and why she’d done it as she had. She took a day to think about it and then she responded. She responded as a black woman who had experienced racism first-hand. Her project, she said, was about that. The letter was complex and thoughtful. If anything was mindless, it was Dabkowski’s wholly inappropriate and unearned ad hominem attack.

Art is grounded in intervention: It is about making you see something you would not otherwise have seen, feel something you would not otherwise have felt, understand a feeling you’ve had but could not theretofore have understood. Art is about disturbance. If it doesn’t do those things, why do it? Why spend time with it?

And college is not a place where you spend good money to stay safely in your comfort zone. It’s a place you go to learn things you didn’t know, confront ideas you didn’t come up with yourself, a place to encounter complexity. A place that doesn’t let you rest in your comfort zone. You can do that without leaving the house.

Both art and college are about dealing with difficult things rather than fleeing them. That is what Ashley Powell did. If your desire is comfort, buy a very soft pillow.

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture at UB, where he is also Affiliate Professor of Art, Media Studies, and Law.