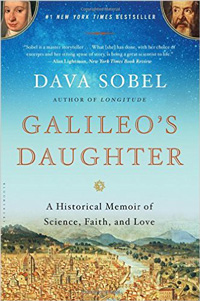

Dava Sobel’s Galileo’s Daughter

What if what you think you know about the world turns out to be wrong and your neighbor can prove it? This question may sound like a hook for some internet-fed conspiracy theory, yet it does not seem out of place in the context of a review of Dava Sobel’s Galileo’s Daughter, a masterful work of historical research that manages to reconstruct for today’s audience, not just the scientific and ideological implications of Galileo’s groundbreaking discoveries, but the sheer shock with which those discoveries were received by his contemporaries. Historians tell us that by March 20, 1610, a week after the publication of the first 550 copies of Sidereus Nuncius or Starry Messenger, Galileo’s most celebrated and vilified work was simply impossible to find. Some of its first readers would coin the expression “nocturnal horror” to describe their feelings of transcendental awe when confronted with Galileo’s “modern” picture of the heavens, which effectively displaced the Earth from the theologically-grounded center of the universe. Sobel’s gripping page-turner captures this complex web of thoughts and emotions in a richly contextualized narrative, but the reader’s true reward comes as we get to see the man behind the discoveries in his daughter’s eyes: a privileged intellect painstakingly cultivated in an astonishing array of scientific and humanistic disciplines, but also a deeply scarred soul, a frail body, and an aching heart; yet always a loving, attentive father.

What if what you think you know about the world turns out to be wrong and your neighbor can prove it? This question may sound like a hook for some internet-fed conspiracy theory, yet it does not seem out of place in the context of a review of Dava Sobel’s Galileo’s Daughter, a masterful work of historical research that manages to reconstruct for today’s audience, not just the scientific and ideological implications of Galileo’s groundbreaking discoveries, but the sheer shock with which those discoveries were received by his contemporaries. Historians tell us that by March 20, 1610, a week after the publication of the first 550 copies of Sidereus Nuncius or Starry Messenger, Galileo’s most celebrated and vilified work was simply impossible to find. Some of its first readers would coin the expression “nocturnal horror” to describe their feelings of transcendental awe when confronted with Galileo’s “modern” picture of the heavens, which effectively displaced the Earth from the theologically-grounded center of the universe. Sobel’s gripping page-turner captures this complex web of thoughts and emotions in a richly contextualized narrative, but the reader’s true reward comes as we get to see the man behind the discoveries in his daughter’s eyes: a privileged intellect painstakingly cultivated in an astonishing array of scientific and humanistic disciplines, but also a deeply scarred soul, a frail body, and an aching heart; yet always a loving, attentive father.

Maria Celeste, Galileo’s illegitimate daughter, is arguably the real protagonist of Sobel’s biographical tale, a gifted and determined mind and a deeply emotive, generous, and caring heart in her own right. Cloistered in a convent since she was thirteen years of age, Maria Celeste would manage to maintain, throughout her life, an unusually close and rich epistolary relationship with her aging father. Her letters reveal unimagined details of her private monastic life alongside her intimate thoughts and emotions penned in response to Galileo’s own letters of which the archive knows nothing. Sobel fills in the archival gap with meticulously researched material and poetic artfulness. Her voice expertly blends Maria Celeste’s archived letters with the historical record and Galileo’s own lifework. The result is a deeply satisfying narrative that brings an ever-growing cast of historical characters to life in unexpected ways. The passage below is an example of Sobel’s layered narrative and her engrossing story-telling craft. The writer manages to meld a discussion of Galileo’s fundamental innovation in Two New Sciences with graphic details of Maria Celeste’s extraction of her own rotting teeth, and news of pope Urban’s stern warning to Ambassador Niccolini, one of Galileo’s most ardent defenders, that all who correspond or otherwise associate with the Florentine mathematician will be placed under Inquisitorial surveillance:

Two New Sciences takes place in a shipyard. Its characters simply dismiss the pursuit of ultimate causes that has passed for science until their time: “The cause of the acceleration of the motion of falling bodies is not a necessary part of the investigation,” declares Salviati. From now on, physics will never be the same.

“The continuous rain,” Suor Maria Celeste wrote in the morning-after postscript to her weekly summary of Saturday, November 12 … “leaves me time to chat with you a little longer, and to tell you that recently I pulled a very large molar, which had rotted and was giving me great pain…”

As Suor Maria Celeste sat writing in the Sunday morning rain on November 13, Ambassador Niccolini again approached the pope for permission to send Galileo back to Arcetri. Urban withheld his judgment. He neither granted nor denied the request during this audience, but pointedly let on that he knew Galileo was enjoying support, defense, companionship, and correspondence of like-minded men –all of whom, Urban assured Niccolini with undisguised disgust, were now under surveillance by the Holy Office (pp. 337-338).

With regards to Galileo’s problems with the Church, Sobel makes good use of Maria Celeste’s letters to offer a nuanced view of the subject, a window into Galileo’s own constant soul searching and his deeply held conviction that he had said and done nothing to damage the Church’s authority. On the contrary, Galileo’s uncompromising passion to understand and explain the work of God is -he sincerely believes- the truest expression of his devotion. Expertly contextualized and meticulously interwoven with other historical documents and Galileo’s own writings, the archived letters of Galileo’s daughter bring history to life in all its vivid complexity. We feel and think the world with Maria Celeste and her father in Dava Sobel’s historical memoir of science, faith, and love.

Dava Sobel will be speaking at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery on Friday September 23 at 8pm, after a formal introduction by Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown. Sobel’s talk, “The Rebirth of the Heavens,” will follow a 7pm VIP wine and cheese reception. The event is part of the 3rd Buffalo Humanities Festival, which features three days of activities, including films, talks, music, dances, conversations and food, all on this year’s theme of “Renaissance Remix,” from the Italian Renaissance to the Harlem Renaissance, and the Buffalo Renaissance. Tickets to Sobel’s talk and the full Festival schedule are available at buffalohumanities.org.

David Castillo is director of the Humanities Institute and professor of Romance languages and literatures at the University at Buffalo.