The Luck of the Irish: Black Mass

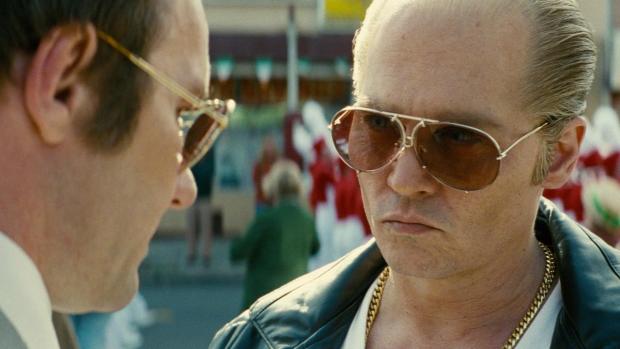

Scott Cooper’s Black Mass is a grim, violent, and sharply visceral crime drama. It also tells an important American story. The life of its protagonist, Boston gangster James “Whitey” Bulger (Johnny Depp), was often brutal, sociopathic, and darkly entrepreneurial. It also reflected elements that have been part of America’s story for a long time.

The storytelling riches in this criminal career have drawn journalists, moviemakers, and legal commentators for decades. Jack Nicholson’s character in Martin Scorsese’s overrated 2006 movie, The Departed, for example, has been said to be based on Bulger, if only rather loosely. There are a number of fact-inspired fictions and journalistic accounts of Bulger’s criminal career. (Ben Affleck and his friend Matt Damon, both Boston-born, are planning their own movie about him.)

Perhaps the rich potentiality of the material daunted Cooper and his screenwriters, Mark Mallouk and Jez Butterworth. Possibly they had some trouble condensing their major source, Boston Globe reporters Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill’s account in their book of the same name. Whatever the origins of the problem, the movie sometimes misses intriguing opportunities and important facts.

Black Mass (the puzzling title may have more relevance for the book) almost never resembles a crude exploitation movie—despite copious bloody brutality—or a pedestrian, by-the-numbers hack job; the skills of the artists involved are too evident for those charges to be laid. But the picture’s approach limits its insights and impact. It’s consistently interesting, sometimes intensely so, and undeniably informative (a function popular movies have always served, if often misleadingly). Given its docudrama take, it had to have this last quality. Black Mass begins with an interview of one of Bulger’s confederates by a federal lawyer seeking evidence against this thug’s leader. Recurring interrogations of several of these men become the framing device as they tell of Bulger’s crimes.

The picture begins in 1975, when Bulger has already established himself as a gang leader, and, to many of South Boston’s Irish-Americans, a prominent, even heroic figure. He and his Winter Hill gang are big players in the area’s drug trafficking, extortion, money laundering, and other rackets. And, not surprisingly, periodic murders, committed for business purposes.

Soon, he’s approach by FBI agent John Connolly (Aussie Joel Edgerton), a boyhood friend, who brings an offer: a much more tolerant attitude toward the gang’s criminal enterprises in return for “intel,” information about the city’s North End Italian mafia. Bulger brusquely dismisses this tender—he’s no fink informant! (At his eventual federal trial this was his most emphatic claim.) But when the proposition is presented as a reciprocal business deal between equals—it can’t have been only incidental that it helped rid Bulger of his mafia competition—he enters into what became a devil’s bargain for the US government.

The movie is really as much about Connolly as Bulger, and Edgerton’s is probably its best performance. His Connolly is ambitiously conniving, and indifferent to ethical, moral, and legal consideration. But there also seems to be an odd admiration for Bulger in his motivation, to such an extent that, at least in Cooper’s film, he can be seen as almost sacrificing himself for this murderously vile man. Depp’s Bulger is, to be sure, frighteningly cold, with a sadistic propensity that now and then surfaces. But his work is more obviously a performance than Edgerton’s character portrait. (And I wasn’t quite convinced by his attempt at a Boston accent.)

The picture’s depiction of Bulger is crimped by its too cursory treatment of two big parts of his story. First, his curious, disturbing relationship with his younger brother William (Benedict Cumberbatch), the eminent, supposedly “clean” Bulger, who became president of the Massachusetts Senate. William knows but doesn’t know in this telling. But the bent, suppressed truths and dramatic possibilities are barely dealt with. And also, the fiercely defensive pride of many of Boston’s Irish-Americans, their regard for both brothers, helped sustain Bulger’s success, and shaped his own deeply corrupt and dangerous personality. Most of his neighbors didn’t share this personality warping, but many managed to suppress its reality. The movie largely misses out on both the personal and popular dynamics.

It also gives short shrift to facts despite its methodical approach. Bulger’s woman, the mother of his small son, just disappears, and the woman with whom he spent 16 years on the lam isn’t even there. Finally, the actual complicity of the FBI isn’t firmly indicated.

Black Mass gets a lot of things right, but its focus skips a lot, too.