Mike Amico’s Obituary—a P.S.

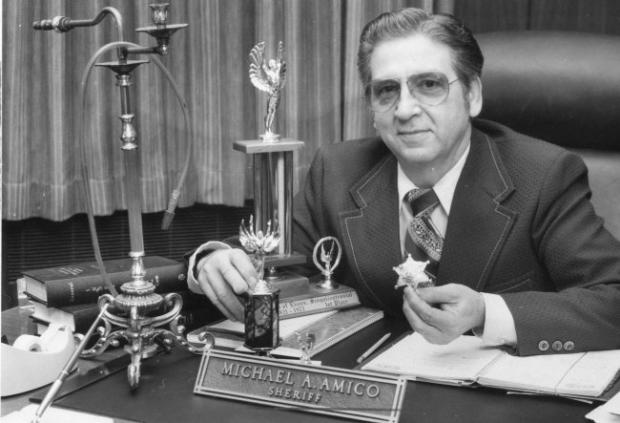

Monday, the Buffalo News published a glowing obituary by Lou Michel for former Erie County Sheriff Michael A. Amico, who died Sunday at his Amherst home. He was 95.

Mike Amico was sheriff from 1969 until his defeat in the 1976 election by Kenneth J. Braun. Before becoming a sheriff, he was a member of the Buffalo Police force, starting in 1947, not long after he got out of the Air Force. In 1962, he became head of the Buffalo Police Department’s narcotics squad.

And that’s where we get to the part of the story Lou Michel leaves out.

I don’t know what kind of job Mike Amico did with ordinary, run-of-the mill drug users and drug dealers. But I do know that he was hell on two groups in particular: UB students and the Road Vultures Motorcycle Club.

Some of the Road Vultures contacted me not long after I moved to Buffalo in 1967. They wondered if I’d write an article about how they were constantly being harassed by the Buffalo narcotics squad. The squad, they told me, would get a drug search warrant, they’d hit the clubhouse and toss everything out on the street, slash the furniture, then would go away. They never found any drugs because, Tommy Bell, the club president told me, “We know they’re always outside the door and we’re not stupid.” Whenever they came, Bell said, they were accompanied by a news crew from channel 7. Irv Weinstein would run stories about the raids, never mentioning that they turned up nothing.

The Vultures had contacted me because I’d been writing about such matters at that time for Atlantic Monthly and The New York Times Magazine. Before I finished the article, Tommy was shot to death and we all got interested in other things.

Mike Amico and his crew would stop and search UB students all the time. They’d pull up the floormats and examine the ashtrays for the remains of a joint, or even a seed or two.

But his main target was UB professor of English Leslie A. Fiedler, then one of the most prominent literature critics in America. That didn’t matter to Mike Amico. What did matter was that Fiedler was the nominal academic advisor to Mike Aldrich’s student organization, LEMAR (Legalize Marijuana).

The Fiedlers had a lot of children, so there were always a lot of people coming and going in their house. Amico sent a young woman in with a mike in her bra (the transmitter, I presume was elsewhere) with which she communicated with the cops lurking down the block. The stakeout went on for some time.

One night she told them there was hash on the third floor sink. They arrested everybody, then told Leslie that if he and Margaret pled guilty to the misdemeanor charge of “Maintaining premises on which narcotic drugs are used,” they’d let the kids go; otherwise they’d charge the kids with felony possession.

Leslie drank bourbon and never used any other drug in his life. He and his wife Margaret took the plea, to protect the kids.

Within weeks, the endowed chair he was offered at UB was withdrawn (at the family’s insistence), his Fulbright to the Netherlands was cancelled, and his homeowner’s insurance was terminated. The Fiedlers went to two other insurance companies, each of which promised to pick up the policy, then backed out. Then their bank then called and said if the insurance was lost they would cancel the Fiedler’s mortgage. He got that back only because a friend wrote the head of the New York Narcotics Commission, and asked him to lean on the insurance company. The commissioner said he probably couldn’t do anything, but he’d give it a try. A few weeks later, without explanation, the insurance company restored the mortgage and the Fiedlers kept their house.

The University created a chair to replace the one that had been withdrawn. Leslie wanted it to be called the Huck Finn Chair, but the University said the couldn’t name a chair after a fictional character. Then he suggested the Mark Twain Chair, but the University said they couldn’t name a chair after a pen name. Then Leslie said, “How about calling it the Samuel Clemens Chair?” They named it the Capen Chair, after an early UB president.

Leslie wrote an article about it for New York Review of Books, “On Being Busted at 50,” that later came out as a book, Being Busted. I wrote about it for The New Republic and, at more length in Disorderly Conduct (1992). I thought it was a nasty, sordid affair then, and I still do. So did the New York appellate court that threw the whole case out.

I also thought it was partly grounded in anti-Semitism: UB was often referred to as “Jew-B” in those years; then-UB President Martin Meyerson, Leslie, and I all got a lot of hate mail, much of which dealt, all the way through or in part, with the fact that we were Jews.

One thing more: Twenty years later, a Buffalo cop I know said, “If I give you something will you promise not to say where you got it?” I must have had an odd look on my face because he then said, “Don’t worry. It’s legal.” I promised. He handed me a large envelope that contained hundreds of Fiedler family photos. It was, he said, from the night the Buffalo narcotics squad raided the Fiedler house. They had no reason to take them, other than meanness. He’d grabbed them and hidden them because he knew they’d be destroyed. He said he’d been holding on to them until he met a close friend of Fiedler’s who would return them and who he could trust not to say how he’d come by them.

A few days later, Diane and I were having dinner with Leslie and Sally (Leslie and Margaret had divorced years earlier). I said, “I have something for you, but you can’t ask me where or how I got it.” I started to explain why this decent cop had been so long partly undoing some damage he’d never wanted to be part of in the first place and had felt lousy about for years.

Fiedler glanced in the envelope and knew immediately what it contained. He held up a hand, stopping me. “I know why,” he said. “Tell him it’s okay. Tell him I said thank you.”

Bruce Jackson was senior consultant for the narccotics law enforcement study done for the 1966 President’s Crime Commission. He presently teaches at UB.