Defining Sculpture at the Albright-Knox

Wall text by the main accessway into the Albright-Knox sculpture from the collection exhibit notes the difficulty of defining the genre for the Modern and Postmodern periods. It’s not just statues anymore.

Maybe the best definition is from Ad Reinhardt, who says sculpture is “something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.”

Not a definition but general distinguishing feature of the works on show from Modern and Postmodern painting is sense of humor. Sense of fun.

One example, Vik Muniz’s Verso (Nighthawks). It’s the back side of the famous Edward Hopper Nighthawks painting—supposedly—we don’t get to see the front, the painted side—propped against a gallery wall, as if awaiting hanging.

Or right as you enter, two comical works from Venezuelan-heritage artist Marisol, each in its own way mocking the monumental statue tradition. Two Generals—namely George Washington and Venezuelan military and political leader Simón Bolívar—riding double on a literal barrel hobby horse with stirring martial music emanating from its innards. (Querying Wikipedia, “horse parts,” I discovered the main, horizontal body portion of a horse—the part the rider sits on, straddles—is called the “barrel.”) And Baby Girl, a larger-than-life-size pudgy one-year-old or so in dress-up dress, with relatively toy-size marionette figure self-portrait of the artist. About her work and outlook in general, Marisol has said, “the world is too serious, I want people to laugh…I want to tell the truth in a funny way.”

The venture into three dimensions from two seems to produce—again, talking generalities—a salutary liberating effect on the artistic imagination. Part of this may relate to the fact that you can make sculpture from anything. (You can make paintings from anything, too, of course, or many things other than paint on canvas, but most painters most of the time stick to paint on canvas.)

From hard stuff. Nancy Graves’s brassy concoction of vaguely bony forms—a sort of vertebral column—that morph into a globe of crazy angle crooks and crotchets, then back into sort of vertebral column again. Or John Chamberlain’s scrap car parts piece—painted sheet metal and chrome bumpers, stuff apparently gleaned from a junk yard. Or soft—Claes Oldenburg’s Soft Manhattan #1 (Postal Zones), a map of the Borough of Manhattan composed of little puffy pillows representing the various postal zones, evoking a butcher’s chart of the various cuts of meat from a side of beef.

“I am for an art that is smoked like a cigarette, smells like a pair of shoes,” Oldenburg said. “I am for an art that flaps like a flag, or helps blow noses, like a handkerchief. I am for an art that is put on or taken off like pants, which develops holes, like socks, which is eaten, like a piece of pie.”

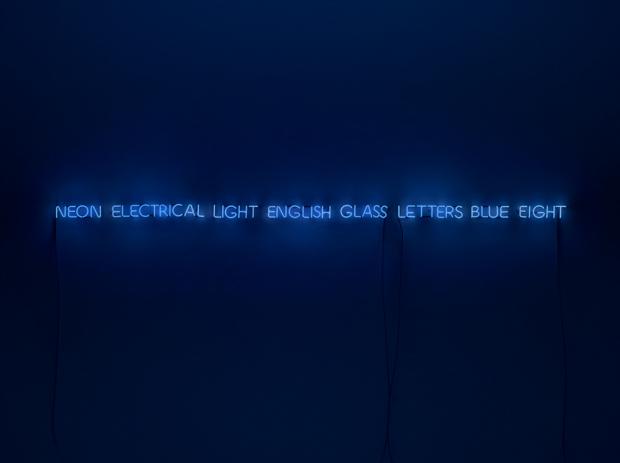

Even from light. Joseph Kossuth’s lovely enigmatic blue neon work entitled—and the neon letters read—One and Eight—a Description [Blue].

(Light artist Dan Flavin’s blue, pink, and yellow fluorescents piece called Untitled (to Donna) is installed as part of the general works from the collection—including paintings and sculptures—exhibit elsewhere in the gallery.)

A piece listed as by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller—a former professor of mathematics who abandoned that métier to become a Buddhist monk—consists of a desk you can sit at with a telephone you can pick up the receiver and listen in on a recorded conversation between the Cardiff and Miller. Half the same room is occupied by Tara Donovan’s otherworldly array of mylar constructions. A little resembling an undersea coral garden in black and silver.

Most of the exhibit main room—at the north end of the gallery old building—is occupied by Polly Apfelbaum’s metastasizing forms and colors carpet of synthetic velvet and dye, entitled Reckless.

The show is called Defining Sculpture. It continues through October 9.