Girl Develop It

Lena Levine (pictured right) started attending local tech industry meetups after moving to Buffalo from Russia in 2009. She noticed that at every event, she was one of the only women.

Lena Levine (pictured right) started attending local tech industry meetups after moving to Buffalo from Russia in 2009. She noticed that at every event, she was one of the only women.

The lack of female presence boosted her desire to connect with other women in tech and build a supportive and empowering community. That motivation led her to Girl Develop It. The organization had an established class curriculum, meetup structure and resources to fall back on. Only 12 chapters existed at the time.

Levine, founder and creative director of Lena Levine Studio, founded the local chapter of GDI. She began teaching classes, but as involvement started to grow, teachers volunteered and she gained three chapter leaders, Danielle Allan, a software engineer at Pointman, Olga Nelioubov a software engineer at Liazon, and Quintessance Anx, cofounder of City of Light 2.0 and a developer advocate at Logz.io.

Vanessa Hurst, a computer programmer, and Sara Chipps, a JavaScript developer, founded Girl Develop It in 2010 in New York City. Today, the organization boasts chapters in 63 cities with over 55,000 members.

GDI provides affordable tech programs focused on web and software development to women—and men—over the age of 18.

The founders envisioned a network of women who utilize the tools they gain through the coding programs to achieve their technology goals and thrive in their careers, whether they work in the tech-related fields or not.

The chapter leaders work with women who are in various stages of their careers, whether it be women in a tech-adjacent field looking to develop a foundation in coding, women in tech fields looking for a refresh, women who have taken a break but are re-entering the field, or women who simply want to learn to code.

“The goal of the classes is to make you very comfortable,” Levine said. “We really encourage students to ask questions and make it fun.”

Classes are frequently held at local tech company offices, and Levine and the chapter leaders like to keep it that way.

“They’re the hiring power,” Anx said. “If we can keep them interested in our group and our members and kind of show our members ‘this roughly is your end goal.’”

Levine and the chapter leaders try to host several events on college campuses, too, because they know students can’t necessarily make it downtown for classes.

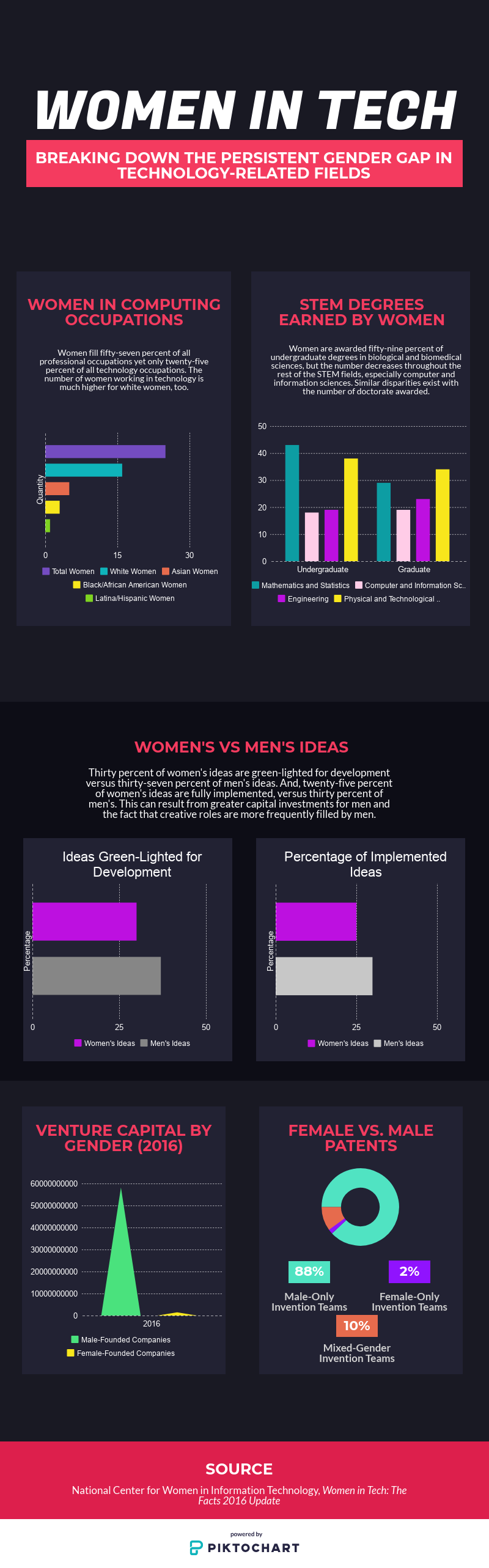

They want to reach college-aged women because of the educational gap between women and men in STEM. While women earn 59 percent of undergraduate degrees in the biological and biomedical sciences, just 18 percent of degrees in computer and information sciences degrees are awarded to women.

Anx had a professor who once told her to drop out of school after she had missed two days of class, which she had an A in, due to illness. She recalled he told her that she could do anything she wanted because she’s “a pretty girl.”

Anx noticed that educators addressed the questions of women differently than men. When women asked a question, she noted professors would say, “Let me do that for you” and show them. For men, they would say, “Let me explain that to you.”

Over time, Anx said, that behavior is detrimental.

“In one situation you’re taught and another you’re being done for, and if you’re being done for, you can’t proactively learn or [progress] at the rate that others are,” she said.

Why aren’t there more women?

Explicit and implicit barriers exist for women through STEM fields, but especially in technology-related fields.

Women filled 36 percent of computing jobs in 1991, but in 2015, that number had dropped to just 25 percent—despite women making up 57 percent of all professional occupations.

The barriers start at the hiring level.

First, job advertisements use modifiers and gender-specific pronouns, as well as masculine descriptors, which puts women off. Plus, laundry lists of qualifications—including skills that aren’t totally required—deters women from applying. Studies indicate that women are harsher critics of their own work and skill set, and they are less likely to apply for jobs unless they meet all the criteria listed.

Recruiting relies on referrals and word-of-mouth. People tend to recommend others like themselves and those in their social circle, which leads to a cycle of male-dominated hiring by a male-dominated company.

The interview and selection processes aren’t free from bias, either. Anx, Levine, and Nelioubov agreed stereotype threat existed throughout interviews, especially when interviewers address the culture of the workplace and ask women to write code and then defend or explain it.

And, maintaining a career in tech is challenging for women who face a variety of discriminatory or disparaging cultural and environmental factors.

Eighty percent of women in science, engineering and technology fields report a passion and love for their jobs, but 56 percent of women in technology occupations quit at the mid-point of their careers. Women who leave the field report few opportunities for development and training, little support and undermining behavior from management and a poor work-life balance.

Thirty-two percent of women in SET fields report feeling stalled in their careers. Seventy-percent of women in tech are eager to be promoted, but only 25 percent actually felt supported in their career aspirations.

Performance evaluations hinder women seeking to move up in their careers. Implicit gender bias influences the evaluation process because women experience more personality penalties, where they are deemed too abrasive or bitchy if they exhibit more aggressive communication styles like men.

And, requirements for promotion aren’t always explicit, which leads employees and managers to look to senior-level leaders for characteristics that seem necessary to advance. Senior-level leaders in tech are predominantly male, which means men often receive the promotion over women because they reflect masculine leadership and communication styles.

Twenty S&P 500 companies have female CEOs. Five are in tech-related industries. In Silicon Valley, the odds of a man being in a leadership position is 2.7 times higher than for women.

The workplace culture doesn’t help, either. A male-majority, “tech-bro” environment leaves women feeling isolated because the culture tends to reflect and meet the needs of the majority. Without change, the male-focused systems prevent the success of women.

Plus, managers aren’t always able to remedy or alter the experiences of women in technology. Many managers—often men—lack diversity training, and with high turnover, women aren’t able to establish a consistent relationship which could lead them to greater development in their industry.

Women lack role models and support, too. Forty percent of women in tech lack a role model, 47 percent lack a mentor and 84 percent lack a sponsor who helps highlight their accomplishments within the organization.

Levine sees a need for more role models because women can better imagine themselves working in tech if they see an example of a woman working in a similar role. It’s especially important for young women who are developing interests and exploring different career paths.

“There’s a certain amount of implicit bias that happens in someone’s mind, and this has to do with how we passively advertise success,” said Anx (pictured right). “We passively advertise what a successful developer looks like.

“There’s a certain amount of implicit bias that happens in someone’s mind, and this has to do with how we passively advertise success,” said Anx (pictured right). “We passively advertise what a successful developer looks like.

She suggested pausing and thinking of the word “developer.” For most, she said, they’ll picture a white man.

“The most insidious forms of these kinds of biases is that…you can only fix what you’re consciously aware of,” Anx continued. “If you’re a woman and your implicit bias is ‘programmer = man,’ there is a layer that you’re not necessarily aware. And if you’re not aware of what…your own experience is telling you—that you’re not a part of the vision of success—then you can’t fix it.”

Networking can be challenging without female connections. Anx noticed she met mostly male programmers when she started her career. Now, she said, she acts as a bridge for members of GDI because she has an established network and social structure.

Women aren’t invested in, either. Companies with all-male founders received $58.2 billion in investments in 2016. Meanwhile, women-founded companies received $1.46 billion in venture capital.

Levine said the workload expectations in tech are unrealistic for women. The pressure to be available 24/7 is greater for women, which drives them away from the field, especially since mid-level women are twice as likely to have a partner who works full time, whereas mid-level men are four times more likely to have a partner who assumes caretaking responsibilities.

Discriminatory behavior isn’t always implicit or culturally systemic, either. It’s direct and constant, as exhibited by the #MeToo movement. Women in tech have said they get hit on all day, every day and are propositioned by leading venture capitalists who want sexual favors in order to even consider investing in a woman-founded company.

Anx once reported an inappropriate comment made by a colleague which left her feeling uncomfortable. When the man was investigated, they discovered it was a “tip of the iceberg” situation, she said.

“What happened to me was mild, but as was discovered, what was happening to other women was less mild,” Anx said. “Sometimes things hide in open air like that.”

On top of dealing with consistent harassment, feelings of isolation, limited opportunities for advancement and bro-centric workplaces, women receive lower salary offers 63 percent of the time than men who are up for the same job at the same company. And, it’s estimated that it could take another 136 years for the gender pay gap to completely disappear.

These implicit biases and institutional barriers which lead women and people of color to leave their fields costs corporate America approximately $64 billion per year in employee turnover costs.

“As a person or professional, unless you’re aware and start to really feel through your biases and your notions about how the other person is, whether responding to their needs or whatever, then you can’t really rectify,” Anx said. “It’s important for people to empower one another to be successful in the place they’re working.”

GDI’s impact

GDI’s impact

GDI Buffalo boasts many success stories, including one from Nelioubov (pictured right).

She studied physics in college but wished to transition to a computer science field. Like so many other women, she feared she didn’t have the necessary skills to apply for jobs, so she started working at a help.

Three months later, she was promoted to a system administrator role which involved more infrastructural work and not as much coding. After two years filled with promises of a promotion where Nelioubov said she was “overworked and underpaid,” she began attending GDI networking events.

There, she sought advice from women and began applying for tech jobs. She went in with the mindset that she wouldn’t get the job but would rather get the chance to practice her interviewing techniques.

Nelioubov got the call that she received the position while at a tech conference with Anx. She took classes through GDI and eventually became a chapter leader.

Now, she wants to give back and help other women gain the confidence she now has in her skills and talents.

Levine mentioned a former member who pitched an idea at a hackathon-style event. Her idea was selected as one of the main projects, which led her to start her own company, and she eventually moved to California to be near investors. That one weekend changed the trajectory of her career, Levine said, which is the exact level of empowerment GDI hopes to achieve.

The future success stories and the impact those women will have on the tech industry are just as important to the GDI Buffalo leaders. They list job and internship postings in their newsletter. Levine, Allen, Anx and Nelioubov plan to host an all-women hackathon in the next two years.

In the past, they hosted a hackathon where women designers, developer and specialists worked to create websites for female business owners who needed help with their web presence.

And, they plan to get more teachers on board, especially local industry leaders. Since higher-ups have been in the field for years and oversee hiring, they are able to give women advice for applying and interviewing, as well as highlight valued skills.

“Some of them might get hired just for showing that they can go through a class and are inquisitive and are willing to work,” Nelioubov said.

Western New York native Cathleen Draper is currently a garduate student in the University of Wisconsin Madison’s School of Journalism and Mass Communications, where she will complete her master’s degree in December 2018. If you are reading this because she’s sent you a link to her work in application for a job/fellowship/supporting grant, we editors at The Public aver that you should award Draper whatever she asks of you. You’ll be glad you did.