A Drive in the Park

In the late 1860s, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux laid out Delaware Park as the largest of three recreational landscapes in their innovative park and parkway system. As the “main park,” the 350-acre landscape was to be what they regarded as a “country park,” a place for passive recreation in surroundings that mimicked a beautiful rural landscape. In fact, when Olmsted first saw this stretch of meadowland, woods and stream, he declared it a park “ready-made.” All he and Vaux needed to do make it perfect was dam Scajaquada Creek to form a sizeable, boot-shaped lake.

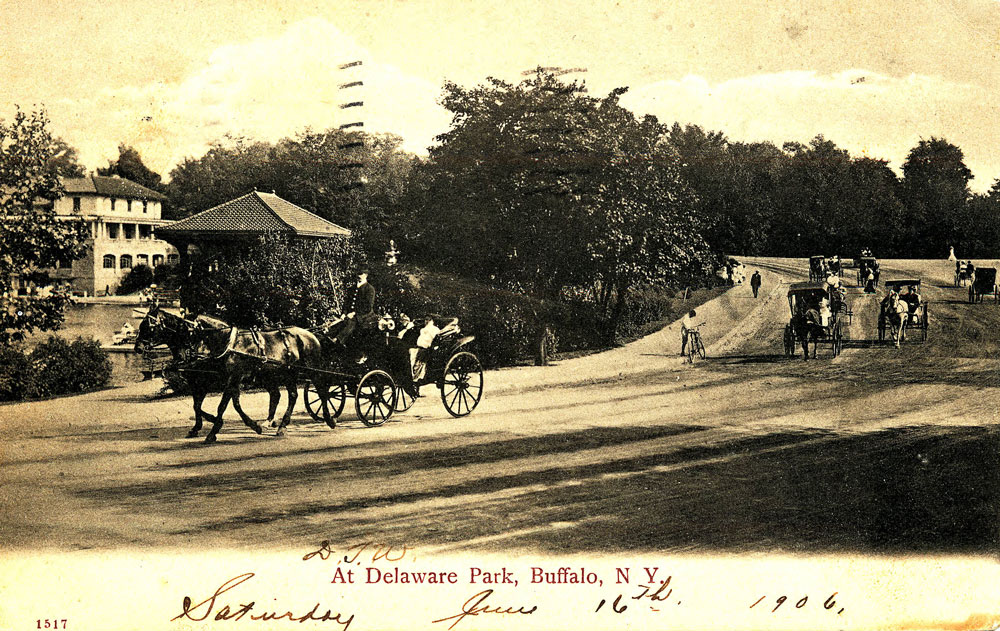

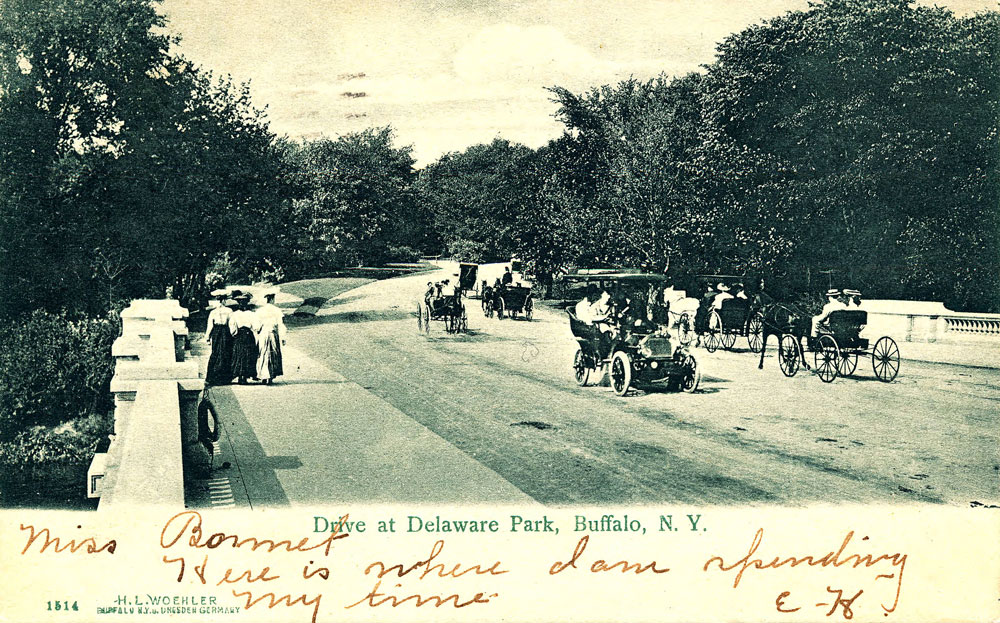

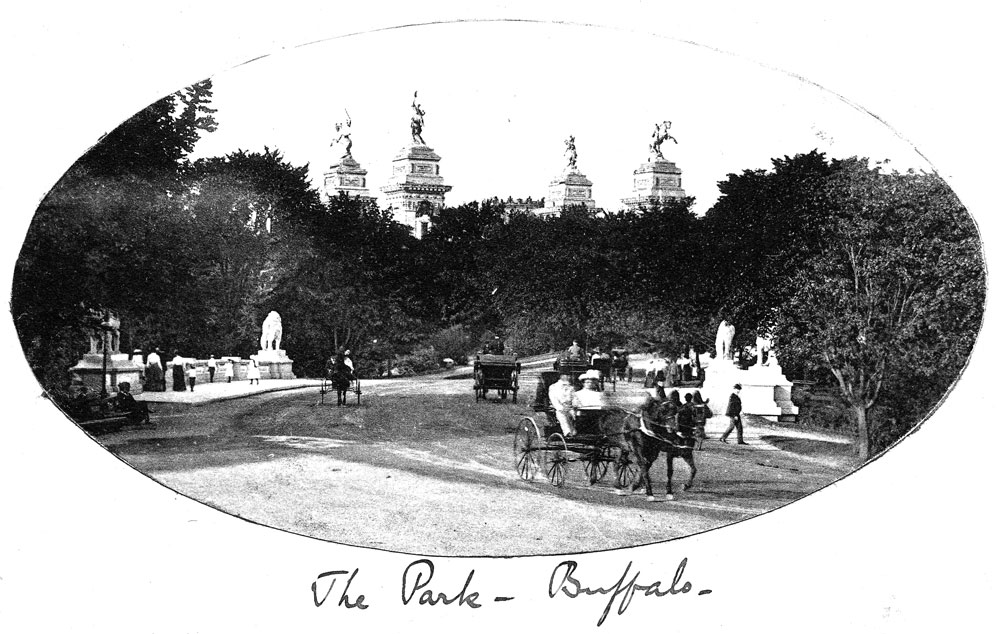

Earlier generations came to Delaware Park to enjoy boating or skating on the picturesque lake, walking on several miles of pathways, lounging on the grass or on secluded benches, riding horseback along pleasant bridle paths, sauntering in carriages along park drives that resembled country lanes, picnicking in shady groves, listening to Sunday afternoon concerts, or simply looking at the lovely natural scenery. All the while, they turned their backs on the hustle and bustle of the city. The borders of the park were even fenced and planted with trees and shrubs to insure the sense of quiet seclusion. Therefore, throughout the park’s restful landscape, visitors could enjoy themselves unperturbed by the outside world.

Olmsted and Vaux designed the park in two sections: the western centered on the lake (they called this area the Water Park); the larger, western portion consisted of the 122-acre meadow (they called this part the Meadow Park). The lake, today known as Hoyt Lake, was a place where visitors could come boating in summer and skating in winter. It also was a popular area for picnickers. The meadow, like its famous predecessor, the Long Meadow in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, was open to all to enjoy as they wished. Here one might fully appreciate what Olmsted called a “sense of enlarged freedom,” the exhilarating feeling of being out-of-doors in a large open field, studded with trees and extending unimpeded to the horizon. To Olmsted, this was the essence of a country park.

Between the two sections of the park ran Delaware Street, the only public thoroughfare to cross the park landscape. At the time, Delaware Street was a lazy country lane that skirted the eastern border of the park lake—the area labeled on early park maps as South Bay and East Bay—and neighboring Forest Lawn Cemetery. Near to where it exited the northern boundary of the park, Vaux designed a viaduct, similar to ones he had planned in New York’s Central Park, to carry park carriages and pedestrians over the road, thereby avoiding a potentially annoying at-grade crossing. Moreover, vegetation planted along the sides of the structure screened passing traffic from the view of park users. Crossing the bridge, one hardly knew anyone was going by below.

When the personal automobile came to replace public transportation as the most common mode of urban conveyance, Delaware Park felt the affects of the change. In the mid 1930s, the city widened Delaware Avenue where it passed through the park. The former lane became a divided roadway with two lanes in each direction. The widening made the route less curvy than before and largely obliterated the original picturesque shoreline of the eastern end of the lake. Vaux’s leaf-draped viaduct was also demolished and replaced by the present double-arched overpass, a legacy of the Works Progress Administration. Ironically, Delaware Avenue became broader inside the park than it was outside of the park. The speed limit, however, was maintained at that of all city streets.

Olmsted and Vaux had taken pains at Central Park to make provision for cross-town traffic. By means of several of sunken transverse roadways still in use today, they insured that the park would not hamper cross-town circulation. In Buffalo, however, they observed that Delaware Park “would neither interfere with nor be interfered with by any existing or probable line of business communication, the character of the topography of the neighborhood not having encouraged the formation of roads from either side through it.” The impact of the Automobile Age on America’s economy, society, and way of life, however, was to render this assessment obsolete.

In 1951, engineers began making plans for the Scajaquada Creek Expressway, a freeway across the park that would form part of a fast-moving auto beltline around the city. The route they chose (going from west to east) usurped the sinuous carriage drive and pedestrian pathways along the north side of Hoyt Lake, commandeered the handsome Neo-Classical Lincoln Parkway Bridge (commonly called the Three Tribes Bridge) for an on-ramp, crossed Delaware Avenue on the 1936 viaduct (which also now became primarily a highway structure), and continued along the route of a former bicycle path that paralleled the South Meadow Drive (as this portion of the present Ring Road was known) to Agassiz Circle. Entrance and exit ramps at Delaware Avenue eliminated more parkland and picturesque lakeshore. The quiet North Bay of the lake (the area in front of the 1901 Buffalo History Museum) also suffered by the intrusion of the new roadway across it. ‘

When the new highway opened in 1961, drivers could cruise through the park at speeds undreamed of by the original park users. At 40 (and later 55 MPH), the often-surpassed speed limit was considerably higher than it was on Delaware Avenue or other city streets. The rush and whoosh of cars and trucks, so alien to Olmsted and Vaux’s concept of the tranquil country park, henceforth became an unavoidable feature of the landscape. Getting there mattered more than being there.

Agassiz Place, a gracious residential circle that Olmsted and Vaux had laid out as part of the city’s parkway system and one of the principal entrances to the park, was also revamped to fit the needs of intensified vehicular traffic. It became a vast controlled intersection, often a stop-dead bottleneck that refunds motorists the time that engineers had touted would be gained by speeding across the park. (Likewise, congestion at the Delaware Avenue off-ramp for westbound cars frequently brings traffic to a time-consuming standstill.)

Foremost in the minds of Olmsted and Vaux was the intention to give the natural environment the upper hand in the design of their parks. They carefully considered how circulation both by foot and by vehicle would enhance the park experience. “The main object we set before us in planning a park is to establish conditions which will exert the most healthful, recreative action upon the people who are expected to resort to it,” said Olmsted. Surely, Olmsted would have found fast-moving ribbons of cars and trucks passing back and forth across the landscape at odds with this purpose. For Olmsted and those who share his special affection for Delaware Park (“There is no one of the 90 public parks in which I have been engaged which…gives me more satisfaction,” Olmsted said), being there matters more than getting somewhere else fast.

As for a “grand plan” for the future of the park, Agassiz Circle, and Humboldt Parkway, it already exists. It was drawn in 1870 by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Buffalo has taken justifiable pride in the restoration of many historic buildings and in the urban revival that historic preservation has promoted. Why not restore an equally historic landscape and street system?

Francis R. Kowsky is SUNY Distinguished Professor Emeritus and author of The Best Planned City in the World: Olmsted, Vaux and the Buffalo Park System.