Clyfford Still and Mark Bradford at the Albright-Knox

Shade

Clyfford Still and Mark Bradford at the Albright-Knox

“I don’t think it’s possible to have a black body and not view that color through the lens of politics in the United States. We are made so hyperaware of race and the raging political debate, and I can’t separate body politics from my body and the body of my work…I understand that, and my art sometimes refers to that. But I don’t want that to be my whole artistic narrative.”

—Mark Bradford

Abstract artist Clyfford Still was apolitical in the extreme. For example, he turned down a series of invitations to show in the world exhibition Venice Biennale because of what he saw as the “political machinations characteristic” of such events. Whereas artist Mark Bradford’s “entire practice is an argument for politically engaged abstraction,” as stated in a catalog essay for the current show of works of both artists at the Albright-Knox.

Some differences between the two men—including generational—Still died in 1980, Bradford was born in 1961—but much also in common, Bradford argues. The show constitutes a kind of dialogue between him and one of his artist heroes. About art and politics in general, and in particular a series of all-black—or nearly all-black—paintings Still produced in the 1950s and 1960s. How could these not be somehow political? So much black, in a period of increasing general awareness of the depth and extent of racial injustice in America, and inchoate but incremental racial justice progress. Period of the lynch mob murder of Emmett Till, but also Brown v. Board of Education, Selma, the March on Washington, and Martin Luther King.

Negative connotations and associations attach to the color black from forever and wherever. But Still did not seem to share the negative attitude about black, Bradford points out. “I don’t see his blacks as fearful,” he said. Wall copy near the beginning of the exhibit quotes the artist himself on the matter. “Black was never a color of death or terror for me,” Still said. “I think of it as warm, and generative.”

1957-D, No. 1 by Clyfford Still

Bradford makes reference to an Albright-Knox story recounted in the catalog about an occasion in the 1960s when Still was visiting Buffalo and touring the gallery with his friend Seymour Knox, Jr. And having a protracted look at one of the gallery masterworks, French post-Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin’s The Yellow Christ. As Knox later recalled, Still wondered aloud “whether people were ready for a black Christ.”

In an aside (pointedly political) comment on the story and question, Bradford observed that “some people are not even ready for a black president.”

In addition to the dialogue about the meaning of black, and art and politics—the folly and futility of trying to separate those two categories—the exhibit offers a new way of looking at the Abstract Expressionist major art mode of the middle of the last century. Generally touted for its non-figurative aesthetic purity, versus contamination with social content.

“I don’t think there is such as thing as ‘pure’ abstraction,” Bradford has said. And “I think all painting is subversively figurative, even abstract painting.”

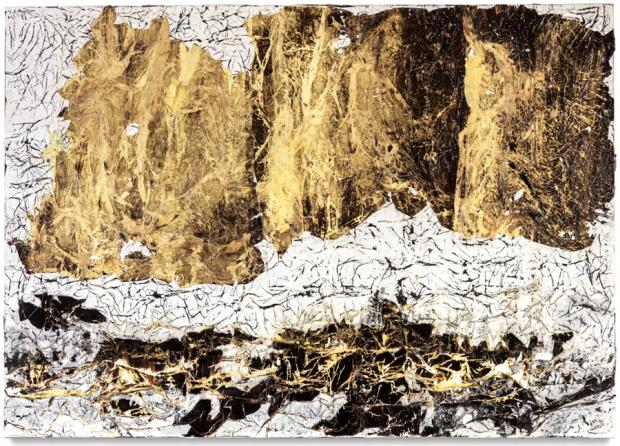

Bradford’s art is variously reminiscent of the art of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and maybe most of all, Anselm Kieffer. What it has most in common with Still’s art—besides the emphasis on black—is layering. For Still, paint layers, differentiated sometimes by color, but more essentially—especially in the all-black or nearly all-black paintings—tone and texture, due mainly to paint application technique, sometimes with a brush, sometimes with a palette knife, a trowel. For Bradford, collaged layers of paint and canvas and other materials as likely from the hardware store as the art store. Plus incorporating found materials from the streets of Los Angeles. That he often then physically excavates into—sometimes with power tools—to expose the underlayers. Indicating an archeological—which implies social content—thematic to Bradford’s art. Suggesting a similar archeological thematic—maybe at a more abstract level—in Still’s layering. Social content interest at a more abstract level.

Layering and the prevalent rough-hewn conjunction of forms and materials. Torn—riven—forms and materials. Metaphorically in the case of Still, literally as well as metaphorical in the case of Bradford.

And the bias toward black, for both artists about subtleties of black. For Still, subtleties of textural differences—matte versus sheen, rough versus smooth. Versus Bradford’s quasi-scientific explorations—in works entitled Legendary and Shade—akin to chromatography analyses—employing chromatography techniques—to reveal the color components of black. Spectral components. Lavender significantly.

“Black is beautiful” was a slogan of the 1960s. An essentially aesthetic message, with socio-political import. In the hope and trust that an aesthetic message would suffice. Would result in significant societal change. It wasn’t. It didn’t. Now the slogan is “Black lives matter.” More political, more urgent. So also with the 1950s and 1960s art of Clyfford Still and contemporary art of Mark Bradford. About some of the same issues, same critical concerns, but more political now, more urgent. In more of a time of crisis. Of less hope and trust.

The dual-artist exhibit is called Shade. It continues through October 2.