Mrs. Gold: The Value of Letting Teachers Teach

Last month, I published an article here about New York State’s current attempt to homogenize education (“Dumbing Down the Kids,” July 14). The article describes a horrific manual which tells teachers what to do each and every minute, and what responses students are supposed to have to those prescribed minutes.

As someone who has been a teacher for 53 years, I found the manual deadening in all regards: It squashes imagination, creativity and individuality among both the students and the teachers.

It is a one-size-fits-all solution to problems in education. But education is no more a one-size-fits-all environment than your feet: You may like the shoes someone else is wearing, but if they don’t fit exactly right you are going to have to squash your feet, have them slop around in a space too big for them, or opt for the Cinderella’s stepmother solution—lop off toes, lop off the heel. Get crippled so you can fit into something you shouldn’t be stepping into in the first place.

After I wrote that article, I got to thinking about the teachers who had mattered to me: Mr. Blue at Stuyvesant, John Shawcross in English at Newark College of Engineering (now New Jersey Institute of Technology), R. W. B. Lewis at Rutgers, John Berryman and Robert Fitzgerald at Indiana, Robert Lowell at Harvard. A few others come to mind.

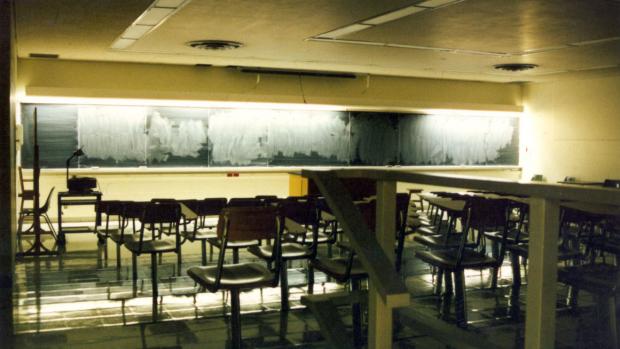

But the most important of all was Mrs. Gold, my third-grade teacher at PS 67 in Brooklyn. Before and after World War II, we lived on Vernon Avenue in Bed-Stuy. During the war we lived in the Fort Greene Projects, and that’s why I was lucky enough to encounter Mrs. Gold.

She realized early on that I was getting through the reading very quickly. (My mother said she’d taught me to read before I started school; I don’t remember that, but I believe it. When Diane Christian and I audition films now for the Buffalo Film Seminars, I remember having seen almost any film we look at made from when I was four on.)

Instead of keeping me on the same schedule as the other kids, Mrs. Gold started bringing me other books to read. She gave me everything we would have read in the fourth grade and when I zipped through that she started bringing me books to read in class and take home.

This is not to brag. I was a fast reader, the way some people are fast runners or others can remember everyone’s telephone number or dance, none of which I am or can do.

Mrs. Gold was free to adapt her teaching in that third-grade class to where I was. I wasn’t paying attention, but I’d bet anything she adapted it to where each and every kid in that room was. She taught the spectrum of kids before her, not pages in a manual prepared beforehand by someone who knew none of those kids, nor ever would.

My entire life, I’ve benefited from her sensitivity and specificity. She turned me loose.

Some years later, my family moved to New Jersey, where the teaching was not unlike what is being forced on New York teachers now. It was boring and it was hell, and I skipped days at a time and got into a lot of trouble.

It was years before I understood that the problem wasn’t that I was a bad kid, but that I was being bored to the core by lousy, non-specific teaching.

That’s what Mrs. Gold in PS 67 understood perfectly well. That’s what New York teachers objecting now to this lock-step model of education, with its one-size-fits all core, hate so much. That’s what the students in those classes, who can no longer get the specific, personalized attention they need and that the good teachers want to and can give them, hate. And they are right to hate it, because they are being cheated.

If Mrs. Gold were here now and were forced to teach by the programmed minute I haven’t a doubt that she’d quit, saying, on the way out, “I’m a teacher; I don’t do child abuse.”

Bruce Jackson, SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture at UB, attended PS 64, PS 5, PS 67, and JHS 148 in Brooklyn before moving on.