Spotlight: Morgan Dunbar on Death Cafes

Nobody makes it out of here alive.

Morgan Dunbar found comfort in her mother’s repetition of this phrase throughout her youth. It reassured her to know that everyone was granted the same experience—just in different forms.

She’d always been interested in death and life transitions, but she found her calling to her “soul work” as a transition priestess—more commonly known as a death midwife—following the death of her four-day-old son Kali Ra in August 2016. Kali Ra was born with severe brain damage, leaving his internal systems compromised, due to negligence from Dunbar’s birth team. In the moments after learning of her son’s situations, Dunbar came into her own.

“I immediately just kind of assumed the role not only of grieving mother, but of death midwife,” she said. “He was on life support, and I played that role of facilitating that sacred experience for him, number one, and my family. It was very empowering, and it was a reclamation of this sacred ancestral work.”

“I just had to keep going with that,” she said. “It felt so right.”

Dunbar became certified as a perinatal bereavement doula and went on to be a part of the Art of Dying Institute’s Integrative Thanatology certificate program. She founded Lighthouse Liberation Transition Support Services, where she works with the dying and their loved ones through the transition from life to death. Her works focuses on honoring the dying’s wishes before and after death, assisting them in acknowledging and creating a legacy, performing healing rituals including anointing and shrouding the body, and providing spiritual, psychological and social support to the dying and their loved ones before and after death.

At an Art of Dying conference, she attended a death cafe and decided to bring it to Buffalo.

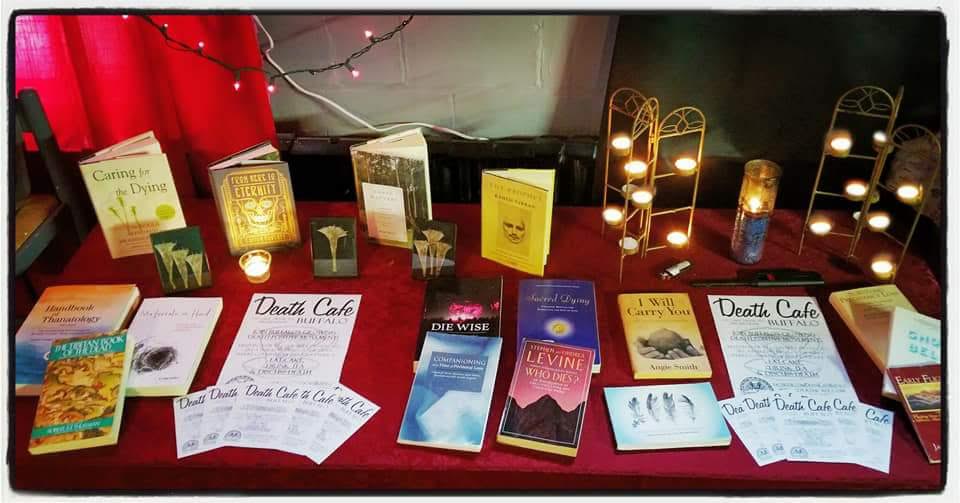

At death cafes, strangers gather to eat cake, drink tea, and discuss death. Cafes have no agenda, objectives or themes; rather, they offer a non-facilitated and group-directed conversation about the end of life.

Jon Underwood created the death cafe in September 2011 in his house after multiple east London cafes refused to host an open discussion about death. Since the first cafe hosted by Underwood and run by his mother, Sue Barksy Reid, a psychotherapist, 6,733 official death cafes have been hosted in at least 56 countries.

Dunbar attended a death cafe in Niagara Falls, then set a date in February 2018 for the first one in Buffalo. The response was overwhelming, with more than 50 attendees at the two-and-a-half-hour session. She and her partner, MacNore Iman, have hosted a cafe once a month since.

Attendees question why we are afraid of death, why we hide our grief, and how to address the grief of others. They also discuss their concerns with death: not having their wishes honored, being on life support and not in control of their own end, and being forgotten. At the most recent death cafe, the conversation centered on New York’s funeral laws.

Despite a free-flowing conversational structure, death cafes are restrictive to Dunbar. She felt there needed to be more—a platform for community engagement beyond a timed conversation once a month.

So, she and Iman started the Threshold Society in June. They came up with the name because of the uncertainty of the transition from life to death and the space that exists between the realms of present and afterlife.

She’s continued to host death cafes, but plans to offer film screenings, speakers series, workshops, and trainings, as well as other death-centered events to give people an opportunity to “engage in something that right now, for the most part, is completely taboo,” she said.

Above all else, the society serves as a response to a lack of community awareness and discourse surrounding what Dunbar calls the conscious dying movement.

The conscious dying movement is similar to the “death positive movement” which grew from discussions, art, and gatherings like the death cafe, as well as the Order of the Good Death, an organization started by Caitlin Doughty, an LA-based mortician known for her frank and informative YouTube series, “Ask a Mortician.”

Dunbar decided to refer to the local initiative as the conscious dying movement because she feels the term “death positive” can be off-putting to those who might be interested but whose experiences with death are anything but positive. Instead, the conscious dying movement focuses on conscious living. To Dunbar, learning how to consciously live means we can learn to consciously die.

“Being more engaged with our mortality is an excellent way of engaging with life,” she said. “If we can deepen into the reality of our mortality, then we really learn to appreciate and be grateful for every day we have.”

The fear of death

In Western cultures, discussions of death and dying and subsequent grief are viewed as taboo. But, it wasn’t always this way. Prior to the Civil War, people held a much closer relationship with death. From 1800 to 1840, the average life expectancy was 44.4 years, which dropped to 40.8 years from 1840 to 1859. And, in the 1800s, child mortality rates exceeded 30 percent.

Homes featured a parlor, which was meant for vigils and viewings before a person’s burial. While men built the coffins, women directed the funeral process, bathing and anointing the body before shrouding it and organizing the vigil period.

But with the Civil War, death came more frequently. Bodies needed to be shipped long distances, and a new technology preserved the dead on their journey to their loved ones—embalming. The practice gained in popularity following President Lincoln’s assassination, when his body toured the country by train. Citizens saw how his body was preserved and began gravitating towards embalming. At-home funerals decreased as the dead were taken from the home, and funeral homes began to grow. The parlor was rebranded as the “living room” by the Ladies’ Home Journal.

Embalming removed death from the home, taking people “from dealing with death all the time and seeing death all the time and interacting with it…to today where it’s all closeted and hidden away, and we’re afraid of it,” Dunbar said.

Death transitioned from an everyday reality and a valued part of life, to a taboo that people fear and refuse to discuss.

“People turn away from conversations about death,” Dunbar said. “People literally hire other people to handle death for them, and so any opportunity that we have to kind of practice and work with this, we reject this.”

The rejection of our own mortality can make death harder. The obsession with our own expectations and how things “should” go means we sweep mortality under the rug, not to be discussed until it’s too late.

If a person doesn’t deal with disappointment well or avoids the discomfort arising from pain and sadness, the end of life can be challenging for them. Saying no to death, pain, and the reality that there might be something to learn from death and dying makes people cling to their bodily possessions and reality.

“Death is about opening up,” Dunbar said. “Death is actually an opportunity to deepen into the real you. It takes away all the facades and all the layers of who we think we are, and it leaves what we actually are.”

Having conversations about death and broadening our perspectives about the end of life, in every form, allows a conscious, moment-by-moment practice of curiosity for life and living in the present.

Dunbar’s work through her death midwife services and the conscious dying movement is an effort to help people get in touch with consciously living so they don’t form expectations for the end of life, which leads to fighting the inevitable.

“Expectation is suffering,” Dunbar said. “When you take away your expectation of how something ‘should’ go, you’re opening to what is.”

Funeral directors as babysitters

Dunbar wants to change the expectation of how to handle death after a person has transitioned. The modern, prescribed response to the death of a loved one distances families from a healing mourning process, she said. Typically, families work with a funeral home to arrange viewing periods and final disposition of the body. If a viewing is scheduled, the body is embalmed and the funeral home hosts a scheduled vigil period for loved ones to attend.

It is legal in every state for families to care for their loved ones at home from death until final disposition, but New York is one of ten states that requires a funeral director to be involved and essentially supervise all after-death care of the body, which impacts or eliminates a family’s right and ability to have an at-home funeral.

“Legally, you can keep a body at home,” Dunbar said. “Legally, you can spend as much time as you want with a body, as long as that body is refrigerated and kept cool. But, good luck trying to find a funeral director willing to open up to that different way of doing things.”

Plus, funerals are expensive, costing an average of $12,000 in the United States. Cremation or immediate burial, which cost an average of $2,000, are still out of reach for some.

“I think when companies and business started to have an opportunity to make money, when capitalism reared its ugly head in the death work, we came to understand an entire industry that stands to profit from our death,” Dunbar said. “The funeral industrial complex has completely choked the life out of any kind of family-directed transition work that used to be extremely healing for people.”

Dunbar said it’s reassuring to have someone to call to facilitate the disposition of a body or guide families and friends through the post-death process, but she feels our automatic response shouldn’t be giving away a “potentially transformational experience that’s gifted to all of us.”

She plans to use the Threshold Society to educate funeral directors about the conscious dying movement and new ways of conducting post-death rituals. With cremations on the rise and expensive funerals—accompanied by expensive and environmentally taxing embalming processes and caskets—decreasing, funeral directors almost need to find a way from their practice dying out, which means embracing green funerals and burial movements, as well as family-directed vigils.

Moving toward at-home funerals doesn’t make things better or make the experience of death more positive, but it does give people options for honoring their dead and greater time to mourn the body and confront death head-on.

“Death never happens on our terms,” Dunbar said. “So, the one thing that we can do to have some semblance of, not control, but some semblance of peace with the experience is to be able to take our time with it and not be rushed through it.”

And, bringing death back to the home offers an opportunity to interact with death and embrace the dying process not as a tragedy, but as a lesson in life.

“To think that every single time life gives us these opportunities to familiarize ourselves with death, we hand it off to someone else and see it as tragedy,” Dunbar said. “Where it could function for us in a way that every time we get this new experience, if we could just take that opportunity to deepen into the inevitability of our mortality and get a little bit more comfortable with it.”

That familiarity with death and embrace of the dying process opens us to a conscious living experience: not just knowing that we are alive and the opportunities life gives us, but living mindfully and accepting everything that comes our way in our lifetimes.

Living consciously and embracing death and the lessons it offers doesn’t make it easier to endure the death of a loved one and feel grief, but it could make us more likely to acknowledge our feelings of disappointment and frustration and less beholden to them.

“When we can be invited to open to all of the gifts of an experience and not just see it one way, that ‘this is a horrible thing that shouldn’t happen,’ and not really allow our mortality to be a daily reminder of the sacredness that we were blessed to ever have any interactions with our loved one at all,” Dunbar said.

By working to spread the idea of consciously dying, Dunbar spreads the concept of consciously living. She believes that if you don’t confront your own mortality, you fall into a pattern of not living your life to the fullest.

And, acknowledging our death and trying to understand our dread for it, whether it be the pain, the unknown afterlife or our fear of being forgotten, we can begin to feel the gifts that death brings us: a renewed zest for life, our inner strength and the beauty of loving people and learning from them.

“People are afraid of something so natural—completely rejecting it, don’t want to look at it,” Dunbar said. “It’s just like these parts of ourselves that we don’t want to feel grief fully, we don’t want to go down into the depths of our psyche and feel sorrow. But, it’s a beautiful thing because that’s where you see where your power is—when you can survive these things.”

DEATH CAFE BUFFALO

Saturday, August 18,1-3:30PM

facebook.com/DeathCafeBuffalo