McQueen, Crazy Rich Asians, BlacKkKlansman

At the risk of sounding more like an oaf than usual, I do not understand the world of fashion. Not at all. I know that there are people who can afford to spend a lot of money on expensive clothing, and I understand that. I realize that if you’re spending a lot of money on a piece of clothing, you want it to be as unique as possible, and that the quest for singularity can lead into the realm of the bizarre. You say to-mah-to, I say to-may-to. But I don’t understand the point of fashion lines that could only conceivably be worn by people who spend much of their time at the kind of nightclubs that only exist in a handful of the world’s cities.

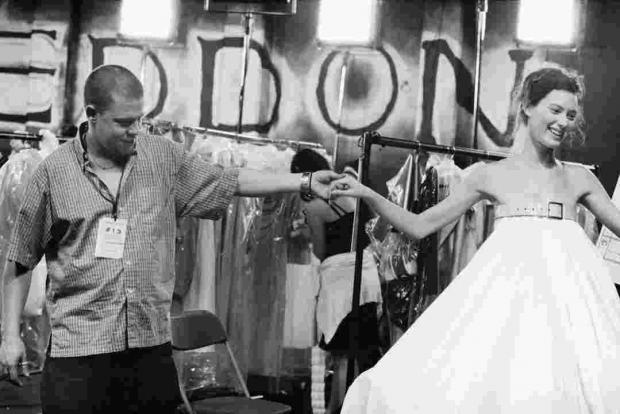

At one point in the new documentary McQueen, the late designer Alexander McQueen is heard saying, “Fashion is a big bubble, and sometimes I feel like popping it.” That goes a long way to explaining his shows, which as shown here existed more as theatrical presentations than as displays of work for sale. The titles alone are indicative: “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims,” “McQueen’s Theatre of Cruelty,” “The Birds.” In one, “Highland Rape,” models were dressed and made up to look as if they had just suffered that most horrible experience.

As his career progressed, McQueen got further away from the very idea of the “catwalk.” His 2001 show “VOSS” had for a centerpiece a large display of mirrored glass, requiring the audience to a stare at itself for an hour. Another put a model in a bulky white dress between two robots, all on spinning platforms, the robots eventually spraying her with paint.

If you’re saying to yourself, “Gee, that sounds kind of cool,” by all means see the film, which opens this Friday at the Dipson Eastern Hills. I’ll admit: A lot of this stuff is pretty cool to see. Born and raised in the working class East End of London, McQueen had no formal education and was free to indulge his odd visions in unique ways. The nexus between his work and the personal demons that led him to commit suicide at the age of 40 aren’t always clear, but they make for consistently vivid cinema. It doesn’t hurt that the film is scored by Michael Nyman, or at least by Nyman tunes that you’ll recognize from The Piano and the films of Peter Greenaway. The movie oddly never mentions McQueen’s work in the music business, designing stage clothing for Lady Gaga, Bjork (for whom he also directed a music video), and David Bowie.

As far as clothing, the stuff that you or I might actually put on to cover ourselves when we leave our houses, his brand still exists and you can visit it online. I personally can’t imagine ever spending $1,800 for sweatpants, but I guess someone out there does.

***

If you are one of those people, you might also be the market for Crazy Rich Asians, which no less than Forbes magazine derides as “wealth porn.” A thuddingly dull and predictable romantic comedy of the Cinderella subgenre in which an NYU economics professor has to adjust when she discovers that her boyfriend is the scion of an immensely rich family, it is notable for featuring a cast of Asian and Asian-American performers in a story about same. My reaction to this is that same that it was to Black Panther: I guess it’s great that commercial films are being made to appeal directly to groups that have previously been relegated to Hollywood’s sidelines, but I can’t get excited that they’re being marketed the same generic crap as the rest of us.

***

Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman shows that entertainment and education do not have to part company in the hands of a skilled filmmaker. It is based on the true story of Ron Stallworth (John David Washington), a black man who in the early 1970s joined the Colorado Springs police department. That took a certain amount of nerve—he was the first non-white cop in the city. But he topped that by setting out to take down the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, in which his first step is to join it.

Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman shows that entertainment and education do not have to part company in the hands of a skilled filmmaker. It is based on the true story of Ron Stallworth (John David Washington), a black man who in the early 1970s joined the Colorado Springs police department. That took a certain amount of nerve—he was the first non-white cop in the city. But he topped that by setting out to take down the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, in which his first step is to join it.

The title is a bit of a cheat. It might lead you to picture a Mel Brooks-ish comedy with Stallworth showing up at Klan meetings and refusing to take off his white hood. In fact, he partners with a white cop named Flip (Adam Driver) for a dual portrayal: Stallworth will play the part on the phone, Flip will be the one who shows up in person. (A reasonable person might well ask why not just have Flip do the phone part as well, but of course suspension of disbelief is central to the cinematic experience.)

That the half-dozen members of the local Klan are hicks who seem to pose a threat only to themselves gives rise to a certain amount of comedy. (So does the casting of Topher Grace as Grand Wizard David Duke.) But if we have learned anything in the last year (and Lee’s film is never unaware of its relevance to the present moment), stupidity does not render people undangerous. Lee has always had a special skill for leaping nimbly between such gaps, and while BlacKkKlansman has its moments of anguish and anger, it never feels like a polemic. It’s a terrifically entertaining movie.