The Siege of Fort Erie, Part 2: The Black Tent

Ghengis Khan and his Mongols were good at siege warfare during their heyday in the 12th and 13th centuries. When a Mongol army drew up outside a walled city, it set up a white tent for all to see. This signified that no one would be harmed if the city surrendered and bowed to Mongol will. They only had a day to think about it, though. On the next morning, a red tent was displayed. That meant that if the city surrendered before nightfall, only the warriors would be killed. On the third day, the tent erected was black, and it stayed in view until the siege was over. This meant the obvious, that no quarter would be given if the city fell. Men, women, children…

What most of the history texts have underplayed, in my view, about the late summer Siege of Fort Erie is that the black tent could have been in waiting for the Americans pinned down inside.

After the British loss at the battle of Scajaquada Creek (August 3, 1814) in Buffalo, things went back to their apparent stalemate at Fort Erie. Around 2200 Americans continued to dig in and stock up. Representing most of the American military strength on the Niagara, they stood as a bulwark against another British invasion of Western New York and another Buffalo burning. Ringing them was an overwhelming force of British redcoats led by General Sir Gordon Drummond, a fiery Canadian-born Scot. Fort Erie was a ticking time bomb in the Empire’s war effort as long as the Americans held it.

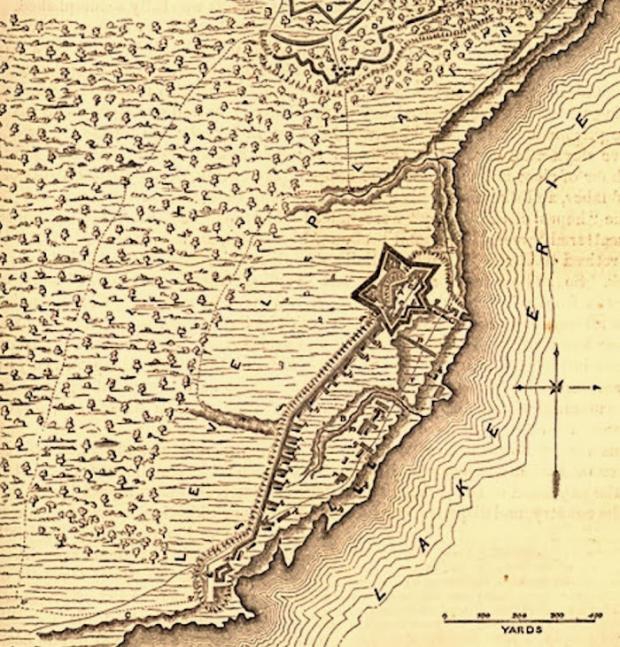

Fort Erie was a five-pointed, stonewalled star made of earth-and-stone mounds. The full formation held two strong stone buildings, but they were neither castle-like nor particularly high, and you could hardly see any of them from a hundred yards away. In fact, that pennon-waving Camelot most of us envision when we think of the word “fort” was long gone just about everywhere in the world by the 1800s. Fort Erie’s low profile and the earthy rings around it were to protect it from the fire of the day’s cannon, which could take down any wall.

Dead center of Fort Erie was a few hundred feet west of the turbulent Niagara in sight of today’s Peace Bridge. Its setback from the river was an advantage when its chief assailants were the ice jams that tended to spill up a surprising distance from the bank. This Fort could not be supplied from the riverside, though, under the pressure of a siege. It should have been a deathtrap. But because of the 700-foot dirt-wall they had built running from the Fort to the riverbank, the Americans holed up at Fort Erie were too well supplied to be choked out. The reality that faced British commander Sir Gordon Drummond was stark. If he wanted to take Fort Erie he’d have to do it by fighting. Back to the head-butt.

This “Cold Steel” Drummond—my nickname—was a grim customer. He was born in Quebec when his Scottish dad served as the quartermaster of the British garrison. He was tough. He had been shot through the throat at the late July battle of Lundy’s Lane, and he was still in command of the force assailing Fort Erie as of mid-August. He was tough on others, too. Read some of his letters after the 1813 burning of Niagara-on-the-Lake (the day’s Newark) and envision him licking his chops about retaliation upon civilians “by fire and sword.” He liked launching bayonet charges at the first glimpse of a chance, as if a big spear-fight was an expression of national character. He would have been the wrong guy to lose a siege to.

Every battle is a mortal struggle, at least for those in the contact point and in range of the day’s weapons. But in most of of history’s battles, the side that first gets the feeling it’s losing can drop its arms and surrender or just flee the field. The victor is usually happy to win the day without further losses. The shoe could well be on the other foot down the road, and no one wants to be in the crosshairs of payback. History has always recognized the siege, though—an assault on a static opponent in a city or fortress—as a special situation.

Behind his walls, the besieged has already turned down the challenge of open battle. He has also rebuffed the besieger’s offers of a merciful surrender. It was standard practice even into the Napoleonic era that the defender had to pay a price for losing a protracted siege. Indeed, many of history’s sieges have ended with deplorable massacres.

To the 21st-century mind, this could seem simple brutality. Far from it; it was a tactic. The siege, you see, was also a risk for the besieger.

If a fort’s defenders could occupy large numbers of the attacker’s men, consume his resources and, perhaps most valuably, freeze his time and position—which open battle doesn’t do—it could be the end for the attacker. Enemies could marshal around him and become more practiced every day at cutting off his supply lines and chipping away at his force. He could run out of materials or fall victim to plague and desertions. A whole campaign could be lost due to a stubborn fort, and not just in the Middle Ages. The two-and-a-half year Siege of Cadiz (1810-1812)—had arguably crashed Napoleon’s Spanish campaign and contributed to the collapse of his whole war effort. Napoleon’s collapse was the reason so many British troops were being freed to join the Niagara war.

While the British home base was a camp well out of cannon range a mile or so north of Fort Erie, the redcoats dug their trenches closer to the American compound, first at 1000 yards, then 750 yards, and, by mid-August, a mere 450 yards away. This is usually the end for a fort. Drummond chipped away with long gun and cannon-fire and waited to catch a break. By August 14 he believed he’d caught it. As far as he could tell, he had been gifted with a couple.

For two weeks cannonfire from three American schooners—the Ohio, the Somers, and the Porcupine – had been shellacking Drummond’s operations from lake and river. These movable, water-borne cannon were bigger than most of the land-versions, and it was harder to hit them back. But in a clever and deceptive raid, a bunch of British marines had managed to capture two of the three tormenting ships, the Ohio and the Somers, and seventy American sailors. Getting this aquatic barrage out of his hair was a major plus for Drummond.

Either through these newly-acquired POWs or some other captured Americans, Sir Gordon had been presented some more welcome news. He was led to believe that the strength of the Americans inside the fort was a couple hundred men short of what he had been expecting.

Drummond’s third lucky break, as he saw it, soon followed. A British cannon shot scored a lucky hit onto an ammo dump inside the Fort that shot a raging smoke cloud into the dusky twilight, elicited a hearty cheer out of several thousand British throats, and made a bang prodigious enough to stop pedestrians in their tracks on the streets of Buffalo. Surely American strength, supplies, and morale had been badly dented. It looked like it was turning into Sir Gordon’s lucky week and that Fort Erie was a plum ripe for plucking. Drummond called in his commanders and made preparations for the obvious: an attack.

Fort Erie wasn’t Camelot. If you are an active person even today you would get the feeling you could run right over most parts of Fort Erie. In 1814 you and your army would have been kept from doing so by the vigilance plus the gun-and-cannon-fire of the defender. You were kept from building up in force and coming in by surprise by the defender’s scouts, the pickets.

If you did take your chances, get by all the above, and come up to those roughly seven-foot dirt-walls surrounding Fort Erie, you started to see that things weren’t even that easy. Below them was a ditch identically deep. Even if you had your fourteen-foot ladders and enough force to give it a go, that ditch and maybe premises around it would have held some surprises, typically what they called abattis, the day’s version of barbed wire.

Abattis—usually said to rhyme and keep meter with the last two words of “that’s my valise”—was basically a mishmash of thorns, rubbish, scrap metal, timbers, and anything else that might give a gate-crasher second thoughts. Its core was usually small felled trees with branches that had been sharpened into spikes, with all the other noxious items grouped around it. It wasn’t the razor wire of today, but at first contact any attacker would give woeful notice and clear it only under a hail of gunfire. Soon the embankments above him would have brimmed bayonets.

Drummond, though, had his plan. He aimed to mount simultaneous attacks on three different parts of the fort. Two powerful columns were to be sent at the northern nexus, the five-pointed fort itself. A third, the biggest, was aimed at the less fortified southern point by Snake Hill, the bottom of that ramp where it met the river. A fourth attack launched by militia and Native allies at the middle of the long American compound was a diversion, a bit of sound and fury to keep men and materials occupied and away from the true attacks. In its supposedly weakened state, the Fort shouldn’t have been able to withstand a single one of these columns. Once the dam broke, the attackers would rush in like a torrent, and then the payback would begin.

Not all the texts choose to mention the detail that Sir Gordon Drummond had planned to keep a company of First Nations warriors out of combat on the night of his assault on Fort Erie. He wanted them intact once the Fort fell, and he made sure that they knew their jobs: to kill as many wounded, surrendering, and otherwise disadvantaged American soldiers as they could.

Most likely these combatants were from western Great Lakes nations lacking allegiances to anyone in Western New York and eyeing the expanding Yankee tide with desperate dread. The Empire’s agents had convinced them that keeping their lands might yet be a possibility if they were good soldiers in its own cause, and that every dead American white was one less onrusher to supplant them. With their help, “Cold Steel” Drummond would get to send the Americans the type of message he had seemed to enjoy sending at Buffalo, Fort Niagara, and Lewiston in the red December of 1813. He made a good heavy in that regard. The Empire was as big on its messages as its deniability. (“Our allies just got out of hand. You know those kill-crazy savages…”) So far, his plan looked good.

Mason Winfield’s most recent book is The Whistlers, a paranormal thriller. Learn more about it and Winfield’s other books, ghost tours, and lectures at masonwinfield.com.