Martha Jackson's Graphics at UB Anderson Gallery

Lithographs and other prints by gallerist Martha Jackson’s stable of major modern artists are currently on display at the UB Anderson Gallery.

Opening with a series by Jim Dine called Crash, a graphic art sequel to a performance piece he did about two traumatic car crash events, one involving his wife and son, one just himself, when he lost control of his vehicle upon hearing on the car radio that a good friend had died. Six lithographs in all, the first five in boisterous black on white circular scribbles and minimal identifiable imagery amid the scribble wreckage. Some onomatopoeic words or fragments—crack, smack, smash—and medical crosses in black not red. The only red—only color—a few red smudges on the work, like transferred bloodstains. The denouement sixth work mainly white with scattered black bits and specks, like the debris left on the street after an accident and official cleanup, and in the center of the piece, the medical cross this time in red.

A statement by Dine describes how Martha Jackson enabled his career. “When I was young…Mrs. Jackson came to me and offered $4,000 for me to stop teaching (I had been earning $4,000 a year teaching elementary school). She wanted paintings and drawings…I was able to stop teaching and paint…I remember her fondly as a very eccentric woman who loved art.” The anecdote probably reflects her relationship with most or all of the artists in the show.

More crosses of a rather different sort in works by Spanish artist Antoni Tàpies. Crosses were a persistent motif in his art, as a Christian symbol, subverted but probably not thoroughly. Sometimes the cross is in the form of the letter “x,” as in one work here in which it seems to function negationally as a crossbar barrier to a doorway of some sort. Tàpies was a teenager during the Spanish Civil War, but his father worked for the republican Catalan government during the war (though his mother was a devout Catholic and saw to it that Tàpies education during this period was in Catholic schools) and the artist’s lasting political sympathies were republican. So that it is tempting to read an anti-fascist political message—as well perhaps as anti-Catholic religious—into such a piece. Though not that the message or import of Tàpies’s usually severely abstract artwork was ever clear and obvious. Nor was he much given to verbally expounding the meaning of his art.

A Tàpies major work in the show is an abstractionist remake of a medieval/Renaissance crucifixion triptych, presenting a gallows form crucifix variant in the left side panel, a gallows with pendant “x” form in the right side panel, and dark to opaque central panel, with just the suggestion in the dark area of the summit of a hill. A political cause he actively engaged in toward the end of the Franco regime—surely reflected in this work, in addition to whatever Catholic Christian sentiments, for or against—was opposition to the death penalty.

Other works of a happier—more sociable than philosophical—sensibility are in bright reds and yellows, the colors of the Spanish flag. In one, a flurry of names—presumably friends—occurs. Another looks like rough outline directions for (or a reminiscence of) a social occasion dance in the round, indicating placement positions for a half dozen or so possibly somewhat tipsy named participants.

Some works by Sam Francis reveal Far Eastern formal influences. One with two boxy forms reminiscent of Chinese ideograms—suppositional ideograms—expressing in the one case enclosure, in the other its absence, its opposite. Openness? Emancipation? Disclosure? Two other mate lithographs are produced from the same prepared stone, that is, with the exact same basic design—reminiscent of a Japanese torii gate form—two polar verticals supporting a horizontal cross piece—with copious overpaint spatter, comparatively restrained in the earlier version, more dense spatter, and consequent frenzied coloristics, in the later version.

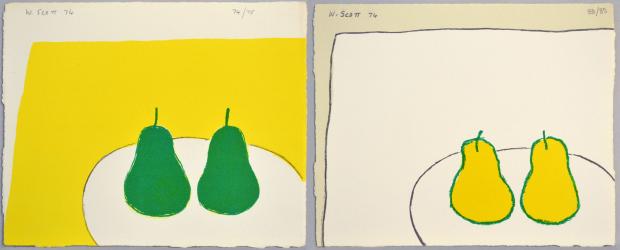

Other works include Joan Mitchell’s three etchings of sunflowers in which it is hard to find the sunflowers; some Claire Falkenstein proto-minimalist intaglios; and William Scott’s more thoroughgoing minimalist lithographs, including four versions of two pears on a plate, in green, in yellow, in black, and just outline. Also, Lester Johnson’s two variants of two similar but slightly different versions of the Three Graces; some Julian Stanczak early Op Art experiments; some John Hultberg slightly futuristic architectural assemblages; Paul Jenkins’s seven-part series of gestural abstracts and one self-portait; and four Karel Appel lithographs of domestic animals in fauvist colors.

The Martha Jackson artists show continues through August 16.