Black Women’s Fight for Dignity

Last month at a community swimming pool in a mostly white neighborhood in McKinney, Texas, a bikini-clad 15-year-old black female, Dajerria Becton, was violently wrestled to the ground by a white police officer. Once subdued, he proceeded to kneel on her nearly bare back and repeatedly forced her face into the grass. Throughout the ordeal, which was captured on a now infamous video, Becton can be heard pleading for her mother and sobbing as she lie prostrate under the weight of the armed man.

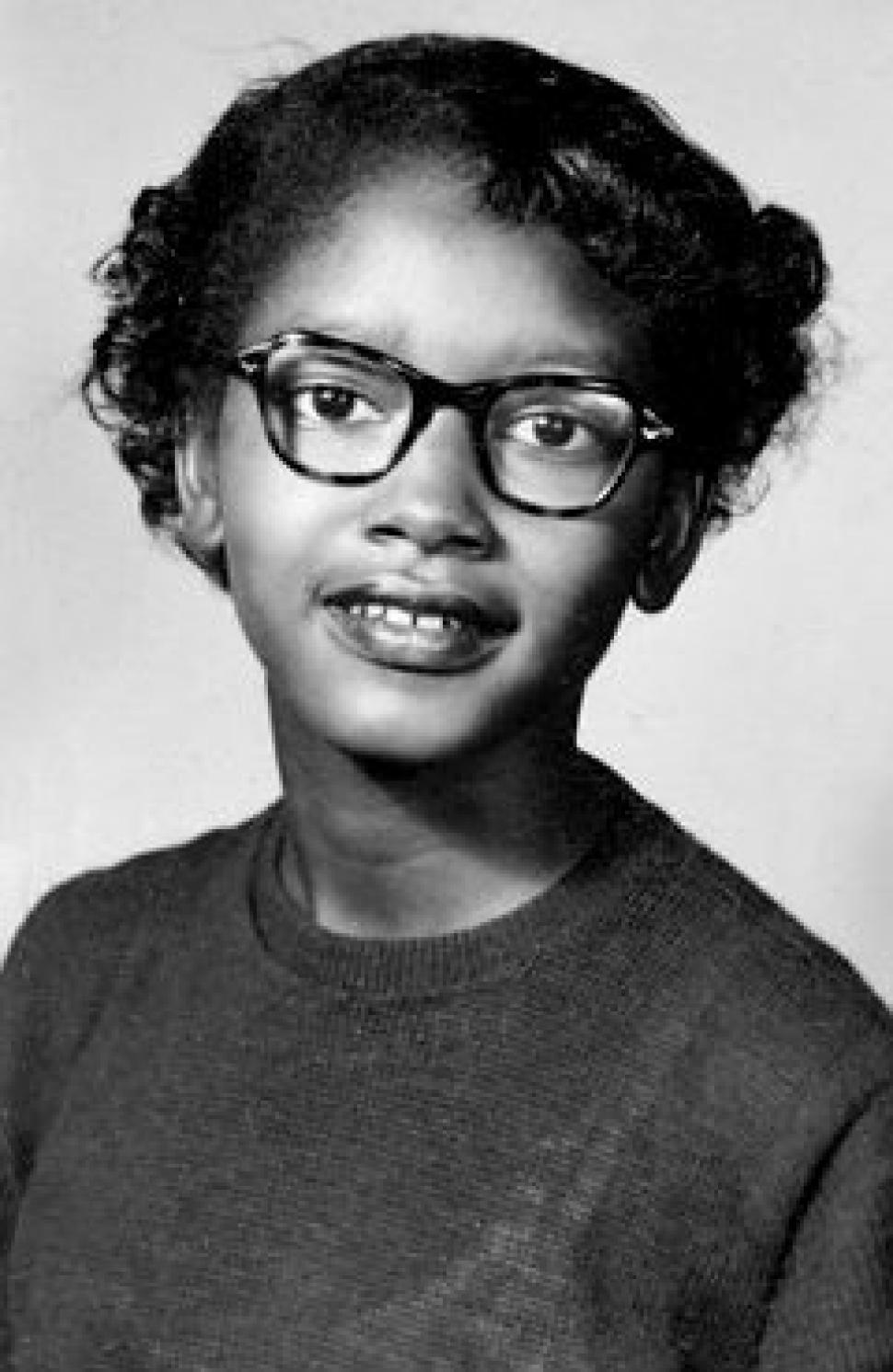

In March 1955, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, also black, was violently pulled off of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, by two white male police officers after she refused to concede to the driver’s demands that she relinquish her seat in accordance with the customs of Jim Crow, claiming that it was her constitutional right to remain where she was. Though she technically broke no law, officers violently dragged the tearful teenager down the aisle to a patrol car. In the process, one of the officers called the teenager a black whore.

In both cases, the girls’ primary transgression seems to have been breaching the color line. That is obvious in the Montgomery incident, where segregation of the races was manifest in the pervasive signage that denoted colored sections and white-only facilities in public spaces across the South. In that time and place, racism was formal and overt, making the wrongs committed by the bus driver and police officers—in hindsight—glaring and difficult to absolve.

In the case of McKinney, the effects of de facto segregation are less blatant but no less relevant. Becton was one of many guests at a pool party gone awry after white residents, apparently resentful of what they must have construed as an intrusion of “outsiders” into their community, hurled racial slurs at the mostly black attendees. To their credit, numerous media outlets, including The Atlantic and NPR, have drawn parallels between what occurred in McKinney and the numerous battles over segregation that erupted at public swimming pools across the country after the Supreme Court ruled separate to be inherently unequal.

But the McKinney incident is about more than segregation. Gendered racism is also at play. Becton’s ordeal stands as a grim reminder that the often sexualized degradation of black female bodies at the hands of authorities is not a thing of the past.

When Colvin was shoved into a police car 60 years ago, she was terrified of being murdered or raped by the very men charged with maintaining order and protecting the people of Montgomery. And with good reason. According to historian Danielle McGuire:

When Colvin was shoved into a police car 60 years ago, she was terrified of being murdered or raped by the very men charged with maintaining order and protecting the people of Montgomery. And with good reason. According to historian Danielle McGuire:

Away from the public glare and in the backseat of a white man’s car, anything could happen. They could take Colvin wherever they wanted and do whatever they pleased without fear of punishment. It was the worst possible situation for a young black woman—something generations of mothers had warned their daughters to avoid at all costs.

In her book At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance—a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power, McGuire recasts the game-changing Montgomery bus boycott, organized just nine months after Ms. Colvin’s arrest, as a movement for black women’s “dignity and bodily integrity.” In the process, she illuminates for readers the abuse black women have long endured.

Indeed, by 1955, Southern police were notorious in African-American communities for their mistreatment of black women, who for decades had been subjected to sexualized verbal and physical assault at the hands of officers with scant opportunity for recourse. In 1949, an intoxicated Gertrude Perkins, 25, was stopped by authorities for public drunkenness and raped by the officers at gunpoint. Later, female civil rights activists and Freedom Riders across the South reported being beaten, fondled, forced to expose their breasts and genitals to male officers and prisoners, and—in what amounted to state-sponsored rape—forced to undergo humiliating, painful, and dangerous vaginal exams.

These examples are not exceptions to the rule, nor was sexualized police brutality against black women limited to the Deep South. In turn-of-the-20th-century New York City, it was not uncommon for officers to harass black women. Their routine mistreatment, ranging from assumed criminality and false arrests to verbal insults and physical assault, contributed to the intense tension between black and Irish residents that sparked the New York race riot of 1900.

This historically pervasive disregard for black women’s corporal autonomy is rooted in the legal codes and gendered racist stereotypes that buttressed first American slavery and then the racial hierarchy that governed post-Civil War Southern society. Under slavery, a black woman’s body was legally not her own, but the property of her owner. He could rape her with impunity, and rape her he did—as punishment, to instill terror, to undermine the masculinity of black men, to multiply his stock of slaves, and for his own sexual gratification. Sexual disrespect toward black women also stems from centuries-old rhetoric that affixed to non-white women the stigma of immorality and licentiousness, which functioned to deny the possibility that a black woman would conceivably refuse the advances of a white man.

This effectively undermined the legitimacy of a black woman’s claim of rape, securing white men’s privilege. At the same time, white society masculinized black women and denied their ladyhood, as defined by Victorian standards. In contrast to white women, who were glorified as delicate bastions of virtuous motherhood in need of constant patriarchal protection, black women were considered physically robust, depraved, uncivilized, and innately criminal. Long after Appomattox, these baseless characterizations persisted. The McKinney video, replete with sexual undertones, shows Becton—a child—being manhandled with a roughness usually reserved for violent, adult criminals. It is not farfetched to surmise the racist stereotypes from America’s sordid past have not entirely disappeared.

I urge you to familiarize yourself with stories of black women throughout history who were subjected to unfathomable police brutality—read them in all of their nauseating detail—and then watch the McKinney video with new eyes. The confrontation becomes disturbing on a new level.

I am not insinuating that gendered racism in the form of police brutality is as common as it once was. Becton was not seriously hurt, and the overly aggressive officer resigned as a result of his actions. (Note that the FBI is currently investigating the death of 28-year-old Sandra Bland while in police custody in Waller County, Texas.) But gendered racism was, for much of our nation’s history, habitual and systemic, and it was not restricted to black women. The other side of the gendered racism coin was the dissemination of the falsehood that campaigns for equality were motivated by black men’s desire to have unfettered sexual access to white women. The historical myth of the black rapist is an essay topic unto its own. And like the myth of the black jezebel, it has long been used by white supremacists to deny African Americans’ civil rights and to justify mob violence against the black community.

In Charleston, Dylann Roof was reportedly motivated to murder nine innocent churchgoers, at least in part, by the misconception that black men prey on white women. The danger of letting gendered racist myths perpetuate couldn’t be clearer.