Scalia's Impotence

Sophistry at the highest levels

In cases like this week’s same-sex marriage case in the US Supreme Court, it is hard not to conclude that, for some of the justices, at least, neither justice nor the Constitution has anything to do with what they’re doing. Rather, it is an antecedent position which they can, using anything from sophistry to blatant name-calling, always justify.

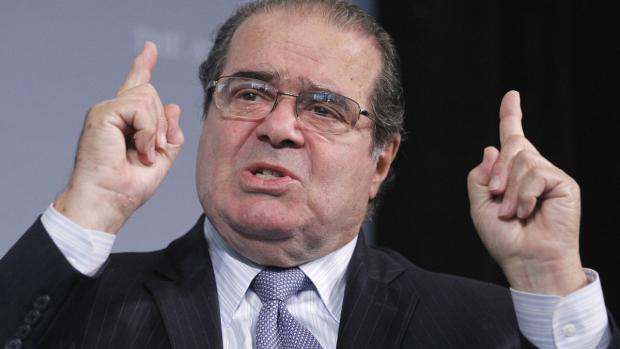

The most accomplished and snidest of the sophists on the current court is the court’s most vocal member: Antonin Scalia. He was one of the four justices who dissented in the June 26 ruling in James Obergefell, et al. v. Richard Hodges, Director, Ohio Department of Health, et al. (The decision also included cases brought by the governors of Tennessee, Michigan, and Kentucky.) The other three, unsurprisingly, were Alito, Thomas, and Roberts, each of whom wrote his own dissent, which is rare, particularly with Thomas, who rarely says or writes anything.

Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion was joined by Ginsberg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan. Chief Justice Roberts filed a dissenting opinion joined by Scalia and Thomas. Scalia filed a dissenting opinion joined by Thomas. Thomas filed a dissenting opinion joined by Scalia. Alito filed a dissenting opinion joined by Scalia. If this reads like a circle-jerk, that’s because it is, although all the dissenters except Scalia limited their reach: Roberts joined nobody; Scalia and Thomas joined everybody on the anti-14th Amendment side.

Equal protection

The 14th Amendment, ratified on July 9, 1868, is the one that provides equal protection under the law to everyone. It is a direct consequence of the Civil War. The key text is in the first section: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

That would seem to make same-sex marriage a no-brainer, which is the essence of Justice Kennedy’s eloquent option, which had two main points: All states had to permit gay marriage, and all states had to recognize gay marriages performed elsewhere.

This isn’t just about romance. The legal implications are profound. The law of the land now says that gay marriages are no different from straight marriage: No special conditions or exclusions obtain when it comes to property rights, medical care, child custody, inheritance, all those things that come along with saying, “I do.” This ruling abolished the adjective: We now have marriage, pure and simple.

Roberts, Thomas, and Alito

Roberts argued that gay marriage infringed on states’ rights. You could make the same argument about the Ku Klux Klan.

Thomas argued that the decision was an insult to human dignity (but, he said, slavery was not). He also argued that “In our society, marriage is not simply a governmental institution; it is a religious institution as well.” By that logic, the Mormons can have multiple wives again.

Alito’s argument was the shortest and most vapid: Gay marriage is something new, therefore it is not covered by the 14th Amendment. He also argued that the one key reason for marriage was children. What about all the straight childless couples—those who can’t have children and those who chose not to? Alito doesn’t go there at all. It doesn’t fit his very religious argument, so why bother.

Scalia’s dissent

There is surprisingly little law in Scalia’s nine-page dissent. His first paragraph is, “I join THE CHIEF JUSTICE’S opinion in full. I write separately to call attention to this Court’s threat to American democracy.”

Yes, you read it right: The threat to American democracy deeply troubling him is the Supreme Court itself. He then writes that it “is not of special importance to me what the law says about marriage. It is of overwhelming importance, however, who it is that rules me. Today’s decree says that my Ruler, and the Ruler of 320 million Americans coast-to-coast, is a majority of the nine lawyers on the Supreme Court.”

He just discovered that? Hypocrisy, or phony naiveté, doesn’t get much balder than that. This is a justice who voted for Citizens United, the 2010 case that said corporations could spend as much as they liked influencing elections. In that case, Scalia wrote his own opinion about how this was a First Amendment issue. Scalia also voted to block a recount in the 2000 election, which gave us George W. Bush and two wars. That case, ironically, also hinged on the 14th Amendment. Scalia had no difficulty ruling in a case about who could buy elections or who would be president, both of which affected far more people than the marriage ruling.

After his opening claim that “what the law says about marriage” is of no “special importance” to him, he spends three pages arguing that since gay marriage was not an issue when the 14th Amendment was passed, it is not covered by the 14th Amendment. That is about as logical as saying that airplanes didn’t exist when the Constitution was written, therefore the government has no authority to regulate air traffic or to inspect our luggage for weapons or bombs before we board an airplane.

“Except as limited by a constitutional prohibition agreed to by the People,” he writes, “the States are free to adopt whatever laws they like, even those that offend the esteemed Justices’ ‘reasoned judgment.’ A system of government that makes the People subordinate to a committee of nine unelected lawyers does not deserve to be called a democracy.”

Why did the 14th Amendment apply when it came to stopping an election in process and making a Republican president and not to gay marriage? Why was it reasonable for the court to license corporations and billionaires like the Koch brothers to spend as much as they like influencing elections, thereby neutralizing or trumping the ability of the majority of citizens to have similar influence? Why didn’t Scalia lament the threat to democracy in those decisions?

Because he liked them; he was part of them. In those cases, democracy for Scalia was what the majority Scalia was part of said was democracy. This time, when he’s in the minority, the Court itself is democracy’s greatest enemy. “But what really astounds,” he writes, “is the hubris reflected in today’s judicial Putsch.” Hubris? They did what the court does every time it renders a decision. Putsch? That word means a violent attempt to overthrow a government. All this decision did was remove an adjective: There is no more gay marriage in America; there is just marriage, for anyone who wants it.

He also complains that all the court’s members studied at the two best law schools in the country, there are no “evangelical Christians,” and only one is from the middle of the country, He writes, “Not a single…genuine Westerner (California does not count.).”

I don’t suppose Californians would be too happy about that one. The Mojave Desert and the Sierra Nevada aren’t Western?

But that parenthetical isn’t just silly and absurd; it is also nasty and ad hominem: Justice Kennedy, who wrote the majority opinion, is from California, a state which, Antonin Scalia tells us, “does not count.” In this case, it very much does.

Then he waxes sarcastic and snide, with lines like, “The opinion is couched in a style that is as pretentious as its content is egotistic…Of course the opinion’s showy profundities are often profoundly incoherent.” And sometimes he is simply incoherent: “One would think Freedom of Intimacy is abridged rather than expanded by marriage. Ask the nearest hippie.” Hippie? What decade is he living in?

He ends with a sentence that is either about jurisprudence or the condition of his penis, I’m not sure: “With each decision of ours that takes from the People a question properly left to them—with each decision that is unabashedly based not on law, but on the ‘reasoned judgment’ of a bare majority of this Court—we move one step closer to being reminded of our impotence.”

Bring on the Viagra! Logic has nothing to do with this, nor does law. Scalia can twist anything six ways from Sunday. (His comments from the bench when the opinion was delivered were even more nasty, sarcastic, and, regarding Justice Kennedy, ad hominem.) I read his dissent and I think of the famous exchange between Alice and Humpy Dumpty (whom he rather resembles) in Through the Looking Glass:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,”’ said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

The last word

The final words belong neither to the most cynical and arrogant member of the Supreme Court or to his 19th-century clone, Humpty Dumpty, but to Justice Anthony McLeod Kennedy:

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right. The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit is reversed.

It is so ordered.

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and the James Agee Professor of American Culture at the University at Buffalo.