The Grumpy Ghey: Keeping Tabs on the Masked Man

We have an tendency to forgive the ills of the motion picture industry in exchange for the amazing stories it brings to life. Anything that causes us to feel so inspired must be good at the core, right?

But the high and mighty entity we simply refer to as Hollywood—a full-blown mythology rather than just a place in California—is often soul-sucking and evil. Perhaps actors and actresses are liars by trade, allowing the star-making machinery that exploits them to feed our most shallow instincts. Being gay doesn’t figure in very well, particularly if you’re male. It’s one of the primary reasons why a separate LGBTQ film industry exists. While gay musicians and novelists are much more apt to blend into the mainstream at some point in their careers, out gay actors interested in film need their own arena.

For all its progressive pretensions (remember George Clooney’s super-smug Oscar speech?), Hollywood is homophobic. It’s an industry in the dark ages. And it doesn’t make much sense until you realize that once an actor is out, he’s not completely believable in a heterosexual lead ever again. It’s different for women. Portia de Rossi and Cynthia Nixon can pull off roles in either sphere, but ingrained stigmas about the sexual behaviors of gay men make it impossible for us to unsee and unknow. It’s even retroactively damaging: Watched any episodes of The Brady Bunch recently? Tell me you didn’t think about the irony of Robert Reed playing the all-American dad or think about what he’d rather be doing while he sat up in bed opposite Florence Henderson, his TV beard. Perhaps you’ve seen an old film on TLC featuring Rock Hudson as the lead love interest…

It’s forced me to rethink my attitude about a particular pair of Scientology-touting guys that have been publicly outed so many times we’ve lost count. I used to scoff and remark about how much more respect I’d have for either party if they’d just come out.

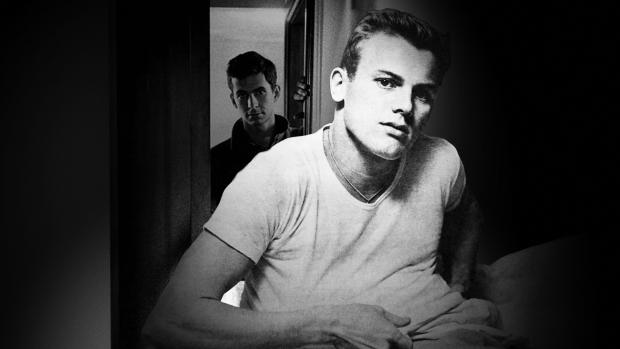

In part, this is what the film Tab Hunter Confidential is about. Director Jeffrey Schwarz’s take on Hunter’s 2005 book hits streaming/on-demand services and iTunes this season after a successful theater run last fall. The film does an excellent job of framing the predicament that Hunter found himself in during the 1950s as the face of young American masculinity. To a mid-century audience, Hunter was the dream boy: blonde, chiseled, earnest, principled. He was wholesome-looking enough to bring home to Mom and overpoweringly sexy at the same time. At first, the fact of his homosexuality didn’t even seem like much of an issue to Hunter himself, who came of age at a time when you simply didn’t come out.

Schwarz, who also directed the biographic documentary I Am Divine, worked closely with Hunter and his partner of more than 30 years, producer Allan Glaser, to make Confidential a compelling look beyond Hunter’s Aryan features—and they succeed.

The film opens with an anecdote about Hunter attending a private gay party early in his acting career. The party was raided. Homosexuality was still illegal and regarded as a mental illness at this time, and he was dragged downtown and booked for disorderly conduct. Attorney Harry Weiss bailed him out and advised him, “You’ve got to be a lot sharper than you are.”

Born Art Gelien in the summer of 1931 to stern parents, Hunter was raised Catholic despite his father’s Jewish heritage. He was taught to squelch negative feelings and internalized a fair bit of self-loathing while enduring his parents’ abusive marriage and subsequent split. High school classmates recalled the remarkable amount of attention he got from girls, who were known to chase him down the hallway shrieking—a scene straight out a movie. It made him uncomfortable, and he joined the Coast Guard to give girls the slip. It worked for a short while, but he was eventually discharged when authorities discovered he was too young to serve.

Relocating to Los Angeles, he was encouraged to follow some acting leads. It’s worth noting that Hunter wasn’t much of what we might call a “born actor.” He learned along the way, picking up knowhow from the gifted folks he was lucky enough to work alongside. An actor’s ingrained ability to become someone other than themselves didn’t come easily to him. It didn’t take long for Hunter to begin feeling fraudulent and dishonest, something his career required of him by its very nature.

When he landed one of the last studio contracts that Warner Brothers issued (the era of studio stables was coming to a close), the corporate PR machine was off and running. Suddenly, his face was everywhere, including on dates with a young Natalie Wood. Warner kept him busy, loaned him out to other studios (profiting wildly while paying him his standard salary), and kept any negative publicity at bay. When he recorded a hit single for Dot Records, Jack Warner was annoyed and quickly established the Warner Brothers record label in an effort to retain every penny generated by his boy wonder. It’s hilarious to think of now: Warner Brothers Records—home to Prince, Fleetwood Mac, and so many other amazing musical artists—was initially established as a vehicle for Tab Hunter’s side career as an early-rock crooner.

Those closest to him watched as he lived a double life, appearing with leading ladies in the public eye then scurrying off to have relationships with figure skater Ronnie Robertson and fellow actor Anthony Perkins after hours. America was so homophobic at this time, Robertson was warned that if Hunter insisted on attending the World Figure Skating Championships, he was unlikely to win. Robertson chose love over victory and lost the competition. Conversely, Perkins was more motivated to sustain an acting career than he was interested in being anyone’s lover: Work-related pressures and betrayals eventually drove the couple apart.

Despite a media leak about the old disorderly conduct charge, Hunter maintained his spot as Warner’s top money grossing star from 1955 to 1959. By the 1960s, he couldn’t keep up the image anymore. “If you were with a man, you’d be sinning,” he recalled. “If you were with a woman, you’d be lying…I found it increasingly difficult to feel good about myself. It felt like being awarded for pretending to be something I’m not.”

Wriggling free of his Warner contract cost him $100,000 (the equivalent to several million now), and the momentum stopped almost immediately. Years of dicey roles, low-budget films, and grueling dinner theater runs kept the bills paid. Then he got a call from John Waters.

The irony was most likely lost on audiences seeing Tab Hunter for the first time in John Waters’ Polyester (1981). They probably had no idea who he was. But it certainly wasn’t lost on Waters, who has forever been obsessed with the plight of the pariah. After all, he used Patty Hearst in no less than five of his films.

In a peculiar, Waters-esque way, Hunter had come full circle when he was cast opposite a 300-pound transvestite, turning Hollywood’s false sense of propriety on its head and earning himself new audience in the process. The role was perfect: a flashy dude decked out in white suit and mirrored shades who’s lying to everyone for his own selfish profit. That his (false) love interest was actually a guy in drag just upped the ante. The liaison with Divine also begat 1985’s Lust in the Dust, the money for which was raised by Allan Glaser, Hunter’s new boyfriend at the time.

Hunter effectively retired from acting in the 1990s. It was never his bag, and despite his inarguable good looks (personally, I think he was even hotter in his 40s), he was unable to find a workable level of comfort in front of the camera as he got older and became more tuned into his sexuality and, surprisingly, a return to faith.

If there’s a moral to the story, maybe it’s that being a successful mainstream actor means the mask never comes off. For some, this perpetual bid to be on stage comes naturally (singer-songwriter Kristin Hersh, a reluctant performer, calls it “the show-off gene”). Those are the folks who seem to survive the scrutiny of a public life without too much strife. Most of us aren’t wired that way, however, which is one of the reasons why fame can be so destructive. At 84, Tab Hunter gets to enjoy a happy ending, which is perhaps what’s most remarkable about his story and so satisfying about the film.