Working the Audience: Inside Out, Aloft

On the surface they couldn’t be any more different: one an animated fantasy about an unhappy little girl that the marketing department at Walt Disney has every right to expect to pack theaters this weekend, the other a dour arthouse drama that is probably on few must-see lists. Yet Aloft and Inside Out share a determination to test standards of story-telling beyond what audiences are used to, and perhaps past what they’re willing to accept.

The latest Pixar production, Inside Out borrows a premise from the 1970s Woody Allen comedy Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sex and the 1990s sitcom Herman’s Head: The main character’s emotions are made into characters, who are seen struggling to maintain equilibrium. In this case they belong to Riley, an 11-year-old girl who is stressed out when her parents move her from Minnesota to San Francisco because of Dad’s new job.

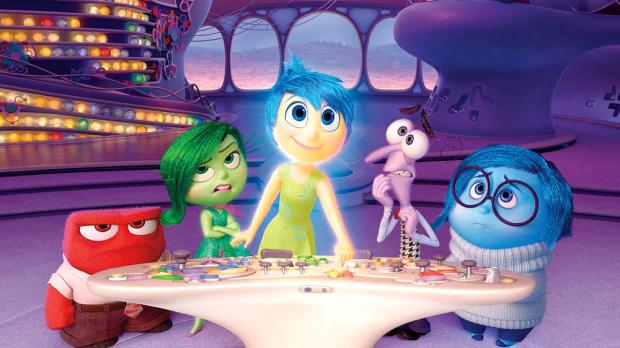

Color-coded as if there was any chance we were going to confuse them, the five emotions are Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Fear (Bill Hader), Disgust (Mindy Kaling), Anger (who else but Lewis Black?), and Joy (Amy Poehler, playing her part as if the character’s real name was Caffeine Overload).

Right off the bat, some of you may say, “Only five? How about frustration, or pity, or pride, or love?” My advice to you is not to go down that route: Be happy that they narrowed it down as much as they did. Because what’s to come plays like something written by a sophomore psychology major the week after he learned about the black box theory of consciousness (and maybe saw Christopher Nolan’s Inception). Writer-directors Pete Docter and Ronaldo Del Carmen set about to concoct an entire interior world, visualizing Riley’s every conscious and subconscious trait as a physical item, carefully organized and utilized.

Of course, an efficiently functioning system isn’t very dramatic. As the de facto leader of the emotions, Joy senses a breakdown when Sadness starts to infect some of Riley’s memories. Her attempts to correct this send both her and Sadness into the inner workings of Riley’s being.

To the filmmaker’s credit, this plays better than it sounds. But not so well that children are going to be able to figure out what’s going on. (The sounds of bored toddlers near the end of the screening I attended were building to a fever pitch by the time Inside Out came to an end.) Docter and del Carmen work too hard to make all of this plausible, which is impossible, and the result is that you find yourself trying to interpret every action by the allegorical calculus they’ve provided. What are we to expect when the Train of Thought falls off its track and tumbles into the Memory Dump? Nothing—they didn’t think it through that much.

Some viewers will probably be impressed that Inside Out contains a sequence that dramatizes the four stages of abstraction. But that doesn’t make it a better movie, no more than a shoehorned reference to Chinatown or a reference to the kind of bears that aren’t found in children’s stories (remember that this is set in San Francisco). It’s all just extra sparkles on a wildly out of control film. Children over the age of six may sit through it simply because, in standard modern animation style, it is fast and bright and has nearly constant movement all through the frame. But in a season when they also released the equally abstruse Tomorrowland, you gotta believe that the management at Disney is going to start pulling in the reins on its creative staff.

If Inside Out stumbles by pushing its concept too hard, Aloft is more likely to disappoint audiences by giving them too little. In a desolate rural environment (the film was shot in northern Manitoba), Nana (Jennifer Connelly) seeks the aid of a faith healer to cure her young son. This possibility is spoiled by the interference of a falcon owned by her other son, who is a few years older. In the process, however, Nana learns that she may also have the gift of healing.

From here the story breaks into two parts. One follows this small family as farm worker Nana comes to grips with her gift while estranging Ivan; the other looks at Ivan as an adult, making living as a falconer but bitter about his past. When a filmmaker hoping to make a movie about his reclusive mother comes looking for his help, he tags along with her, in the hope of putting his past to rest.

I’ve given away as much of the plot as half the film’s viewing time would provide you, for which I may own you an apology. But Aloft is more about mood and insinuation than story. When the film is over, the story seems rather less interesting than it might have been had it played out more conventionally, though it also seems unfinished. This version is between 15 and 20 minutes shorter than the one shown at film festivals two years ago, where it was not well received; whether writer-director Claudia Llosa approved those cuts I do not know. And yet the unanswered questions here stick in my mind more than the overworked hurly-burly of Inside Out, which in the end has nothing more to say than that joy and sadness go hand in hand.