Color Camouflage

“I very well remember at the beginning of the war being with Picasso on the boulevard Raspail when the first camouflaged truck passed. It was at night, we had heard of camouflage but we had not seen it and Picasso amazed looked at it and cried out, yes, it is we who made it, that is cubism.”

— Gertrude Stein

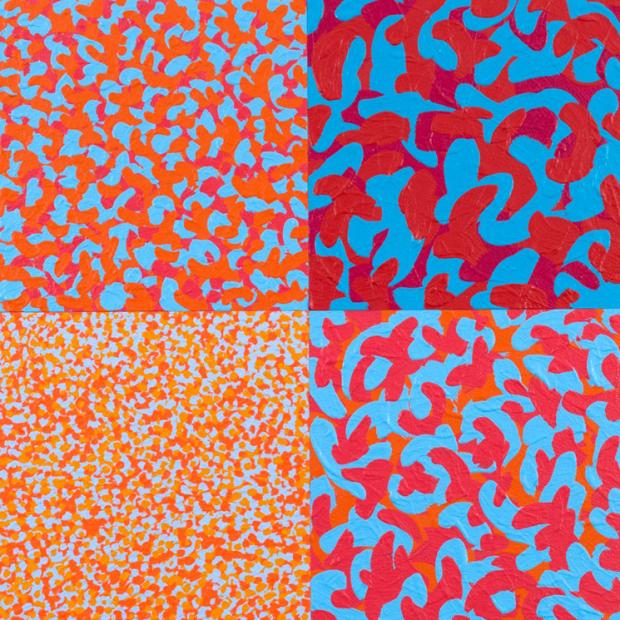

Distinct blocks of confetti daubs of paint in two or three colors transform by quantum increments of relatively larger and larger patchwork construction paint swirls and changing colors—or sometimes the same colors—upward oblique across the surface of Robert Swain’s current paintings on view at the Nina Freudenheim Gallery.

Art about color as content. An introductory note to the exhibit says that as an artist and teacher at Hunter College in New York City for the past five decades, the solo subject matter of Swain’s artwork has been color sensation. How color stimulates and effects human perception, and how colors interact. As much physics and physiology as aesthetics, it seems. Or physics and physiology as aesthetics. For where are the lines of demarcation? And touching on some art historical—and general historical—matters in the process.

In an artist’s statement, Swain gets into specifics. “Color is a form of energy derived from the electromagnetic spectrum that stimulates our perceptual processes and is instrumental in conveying emotions.” He notes that a particular color or colors can be “culturally encoded, projecting content through symbolism and associations,” but asserts the origin of such encoding is in the way the energy—wavelength—of a particular color or combination of colors generates feelings in a human subject. That is, the wavelength energy of a particular color or colors produces physiological changes in the human viewer.

He points out how “in some cultures, red is associated with danger…[but] when pure red is altered, its emotional attributes change, as in the stability associated with red earth colors, or the whimsical fluctuation produced by pink.” (Actually, studies by physiologists and psychologists have found that pink—bubble-gum pink—has a notably calming or passivity effect, reducing violent or aggressive feelings. In experiments, painting detention institution cell walls pink has been effective in reducing inmate assaults and similar hostile or erratic behavior. Football coaches have painted visiting team locker rooms pink in an attempt to diminish their opponent’s fighting spirit.)

Whereas green has very different associations. But when red is presented in association with green, the contrast may heighten the effect of one or both of the colors, and “the experience resides in the energy generated by the convergence of these unique spectral wavelengths,” Swain says.

Lots of red and green combinations—and variations of red and green from pink to purple and yellow to khaki—in the works on display, in blocks of varying combinational densities and an overall textural painterly technique. Swain’s previous works were mural-sized—the current works are of more reasonable dimensions—and consisted of pixel blocks of single colors, changing from block to block. The painterly patchwork camouflage technique is an innovation.

One of the most interesting art history and general history literal coincidences—but cause or effect possibilities could be debated forever—is the birth of Cubism and associated flattening of the painterly canvas modern art key phenomenon at the same time as the first large-scale development and use—by humans anyway—of camouflage, the purpose and function of which was to flatten the appearance of a three-dimensional object—making it hard to see, hard to recognize—by breaking up the visual surface of the object, much in the Cubist manner. Right around World War I time. (The large-scale development and use of camouflage by the military specifically for World War I.)

The essentially camouflage patterns of the color combinations large and small—in daubs or swirls—in the Swain works recall and represent the modern art history flattening effect crucial development.

The Robert Swain exhibit continues through June 22.