Buffalo Esports Changes With Industry

Adam Rosen, who runs a network of college video game clubs, says the general public is wrong about video game culture. It doesn’t promote violence, kill brain cells, or lead to years without communication with females. Rather, it’s the “next big wave,” and, he says, parents should view gaming just like they view Little League, scouting, soccer, or ballet.

For nearly five years, he and Tespa, the company he co-founded, has been fighting the gaming stigma and working to prove gaming is not a waste of time or reserved for loners who live in basements. It has all the attributes and learning potential of traditional sports, he says.

“When I think about sports, it’s cultural. You grow up, you play in Little League, and progress sometimes up to college or pro teams. It’s very familial—families really come together to support it,” Rosen said. “People recognize it as a force for good, a way to better yourself, and it’s a really close community. So because of that you have this really broad cultural acceptance and celebration of sports, and I think we have a huge opportunity to build the same thing.”

The numbers and the money support him.

The market for competitive video games that pit strong (and increasingly professional) gamers against each other is exploding. It even has its own name: esports. Last year, it was a $655 million industry. This year, it’s predicted to exceed that by 38-percent and jump to $905 million. In 2019, it’s expected to hit $1.1 billion in revenue.

The big difference from traditional sports is, of course, that you are not moving your body or showing physical prowess, which was always the measure of greatness. So how did video games evolve from being viewed as a waste of time to an outlet for professional players to earn salaries upwards of six figures?

Tespa has over 220 campus chapters in the US and Canada and hosts the Tespa Collegiate Series, a group of collegiate esports competitions which have awarded over $1.29 million in scholarships through events and tournaments.

Rosen said Tespa is combating the stigma associated with gaming. He said video games should no longer be viewed as a waste of time or something you crawl up in your basement and play for hours. Instead, it should be considered an equal to traditional sports.

Rosen is excited to see esports continue to grow into an even larger market with professional and collegiate leagues across the globe.

“We’re on track for [esports] to be just as big if not bigger than traditional sports,” Rosen said. “Traditional sports have the pro leagues, but also amateur and grassroot leagues, as well as a large fanbase. We have this with esports already. As soon as people start to realize the ecosystem that already exists, more people will jump on board and viewership and players will increase. I’d say in the next five years I could absolutely see some of the more popular titles being as popular as the Buffalo Bills and Sabres.”

As the industry continues to grow, so does America’s interest in the phenomenon.

TBS’s ELEAGUE has broadcast esports on Friday nights since 2016, and fans of “League of Legends” watched 274.4 million hours of competition on the streaming website Twitch in 2017.

The average weekly viewership for NFL games during the 2017-18 season was 14.9 million viewers. With a 16-game season, viewers watched roughly 238 million hours of regular season football last year, falling short to just one videogame’s viewership, which is close to reaching 300 million annual viewers.

Like most professionals sports, esports has established leagues at the collegiate and professional level and broadcasts to hundreds of millions of viewers across the world.

Robert Morris University in Illinois created a scholarship-sponsored team for the world’s most popular esports title, “League of Legends” in 2014. In four years, a national governing body—the National Association of Collegiate Esports—has formed and includes upwards of 50 varsity programs.

In Buffalo, members of the gaming community are finding success in the esports industry.

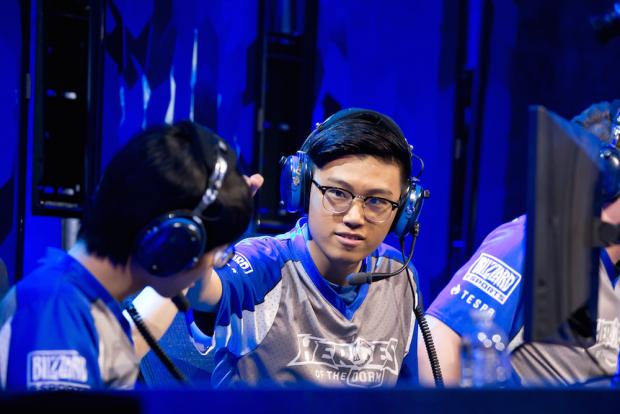

Allen “FantaFiction” Hu, started playing Blizzard Entertainment’s popular video game “Heroes of the Storm” seven months ago for fun. Last spring, he and his teammates traveled from Buffalo to Los Angeles to play for over $500,000 in scholarship prize money.

Hu, a junior at the University at Buffalo, participated in “Heroes of the Dorm,” the largest collegiate esports tournament in North America, which offers full college tuition to each member of the winning team. The team, “Improbabull Victory,” made up of five UB students, lost in the finals, but highlights Buffalo’s—and the nation’s—growing interest in esports.

Hu thinks UB could benefit from creating a varsity esports program. After finishing second out of more than 300 participating teams—many from funded varsity programs—he feels confident UB could be a competitive powerhouse at the collegiate level.

“There’s enough competition out there that it makes sense for UB and other schools in the area to start investing in esports,” Hu said. “It’s not just “Heroes”, some schools have teams for four or five games, and all of the students on those teams get full-ride scholarships. It’s honestly starting to catch up to college football and basketball.”

Tespa studies found over half of college students now actively identify themselves as gamers. Whether students play casually or with the hopes of making it pro, it’s evidence the stigma about video games is changing.

The University at Buffalo isn’t a Tespa chapter, but has active members who host monthly competitions on campus. Students compete against each other for prizes and in-game-credits provided by the organization. Rosen said from small on-campus events to national tournaments, he views Tespa as platform for students to meet new people who share the same hobby.

He added it’s only a matter of time before esports becomes a fundamental piece of the collegiate experience. Rosen said live esports events will continue to grow, becoming a major part of the gaming experience. He feels the level of production,

With tournaments and regular season games selling out Rosen said investing in all aspects of the esports experience is key to furthering the industry.

“Look at what we’re doing with ‘Heroes of the Dorm,’ where there’s scholarships on the line. We’re taking these students, they’re flying across the country, they’re competing and representing their universities, and I think it’s tremendously positive,” Rosen said. “When you’re an administrator or a faculty at a university that doesn’t quite get gaming or esports yet, you can’t not look at HOTD and not get it. The fans shouting from the audience with faces painted in school colors, the analysts desk, the announcers, everything we know and love about collegiate sports we see in collegiate esports.”

Rosen said at the pace the esports industry has grown since Tespa’s conception, he expects most colleges to have varsity programs in the next five years. As for Tespa, he hopes to continue using the platform to create the esports equivalent of the NCAA.

“Looking forward, I think varsity teams will be the norm, it’ll be odd if there’s a college without one,” Rosen said. “Professional leagues have been established, like with “Overwatch” which has 12 teams all across the world who participate in a regular and postseason, just like any traditional sport. I think bringing that to collegiate esports scene is accomplishable and will really help cultivate that broad acceptance found in traditional sports.”

Schools in the area are already starting to invest in esports. Daemen College became the first private institution in the Buffalo Niagara region to create an esports team as a part of their Games Club and built an esports center for students in January.

Professional teams and players from Buffalo have also played in national tournaments for games including “Hearthstone” and “Counter-Strike: Global Offensive,” and the No. 3 globally ranked “Tekken 7” player lives in Buffalo.

Many local pros practice at GameOn LAN, an internet café and gaming center located on Delaware Avenue in Kenmore, which offers players high end equipment and a professional space to practice their game. Co-owner Josh Lonczak said since opening in 2015, he’s seen esports thrive in Buffalo.

“There’s definitely a strong support for esports in Buffalo and it’s still growing,” Lonczak said. “The community’s interest and support hasn’t plateaued. We have a massive fighting game community, then you have the other side of the community they show up for “CSGO” and “Fortnite;” which just announced $100 million in prize pools for 2019.”

GameOn is currently the only LAN center in Buffalo, as others like CyberJocks have closed in recent years. Despite this, the center is getting itself and its players noticed on the global stage. The popular fighting game forum “Shoryuken” recognized the “Rumble in the Tundra” competition held at the center, prompting outsiders to view Buffalo as an esports hub, according to Lonczak.

Hu appreciates Buffalo’s gaming community, but thinks it still has a long way to go. With a target audience of young adults and millennials, Hu thinks esports needs to be marketed as something that’s relatable even to older fans.

“It’s a niche community, compared to other sports it won’t be that big,” Hu said. “Unless companies can [reach a larger audience like traditional sports,] it will only be something viewed by people that play games and enjoy them.”

Lonczak agrees the community could be bigger, but encourages people to reconsider how they view the esports industry. He feels the growth the industry has made in the past four years is remarkable, and if it continues, it will rival traditional sports in the future.”

“People are surprised when they learn about esports and how similar its become to traditional sports,” Lonczak said. “Look at Mark Cuban, he owns the Dallas Mavericks, but he also owns a professional “League of Legends” team. Video games have become a platform for people to earn an impressive salary. It’s just as hard as making it as a traditional athlete, but I think in the future, esports leagues will become the norm and I wouldn’t be surprised to see Buffalo have a professional team.”

Max Kalnitz is the senior news editor at the University at Buffalo’s student newspaper The Spectrum and can be reached at max.kalnitz@ubspectrum.com.