The Poems of Norma Kassirer

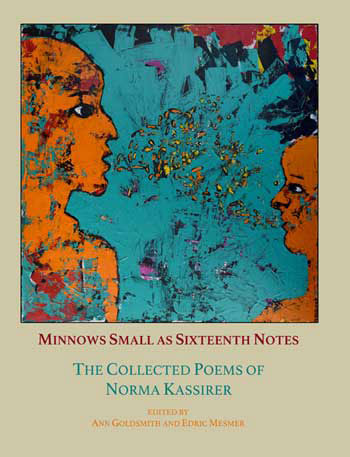

Minnows Small as Sixteenth Notes

Minnows Small as Sixteenth Notes

By Norma Kassirer

BlazeVOX Books, March2015

Tell me about this book.

On June 27 of this month, 5pm at Brighton Place, there will be a book launch for Minnows Small as Sixteenth Notes: The Collected Poems of Norma Kassirer, a book I coedited with Ann Goldsmith, published by BlazeVOX [books] of Kenmore.

What influenced this book?

A young poet named Paige Melin was searching the holdings of the Poetry Collection of the University at Buffalo for poems about the weather by local writers. She showed me her list, and asked if I could think of anyone she had left off. I said: “Norma Kassirer,” then added, “but there is no book of her poems.”

Where does this book fit into Kassirer’s career as a writer?

Most readers will know Norma through her novels for children, Magic Elizabeth and The Doll Snatchers (Viking, 1966 and 1969), but she also wrote short stories under the influence of surrealism, and the numerous poems collected here. Many of these poems were undated, and exist in multiple versions; all were arranged alphabetical by title, and Ann and I have retained that arrangement for the book.

Perhaps what’s most interesting is how Norma came to write poems later in life (though she always read poetry), having primarily written fiction for many years. When I published her short story cycle, Milly, she told me that the line between poem and prose didn’t seem to matter to her anymore. This has always fascinated me as a reader of her work, and it is demonstrated in the lyrical narrative she brings to these pieces.

This aesthetic intuition was also a difficulty when trying to publish her work, as many literary journals and publishing houses would respond that her poetry was too much like prose and her fiction too poetic. It would be different now, I think, with the attention many journals and small press outfits are giving to the prose poem and flash fiction. Perhaps Norma’s audience is now here!

If you had to convince a friend or colleague to read this book, what might you tell them?

The many readers who will have heard of Norma Kassirer will not know the breadth of her artistic output. I would tell these readers that Norma was someone who engaged art every day—in stories, poems, paintings, artist’s books, and collage.

In a write-up about her in the Buffalo News, R. D. Pohl mentions how Norma Kassirer influenced several generations of Buffalo artists—and yet there is no definitive book of her work! This is a first step toward that: to collect her poems, which she worked on over the past few decades, to be read alongside the stories collected in The Hidden Wife (Shuffaloff, 1991), the aforementioned Milly (Buffalo Ochre Papers, 2008), and her novella, Katzenjammered (BlazeVOX, 2010).

Tell us what you know of Norma Kassirer’s process: pen and paper, computer, notebooks…

I know that Norma wrote every day, usually in the morning, and was an ardent reviser of her work. Something else that strikes me is the way her work seems of a whole: a notebook of asemic writing, a surreal tale of a lost doll and a cultural revolution, a large painting called Mechanical Rabbit (now held by the Burchfield Penney Art Center)—all spring from a signal signature.

How would she have handled a bad review of her work?

I think silence has been the most troubling response regarding Norma’s work. She had many promising publishing opportunities which simply dissipated; I believe to some extent this is endemic to all writers, especially with the way publishing falls victim to economy.

But the losses I’m talking about were more tragic in nature…Norma’s books for young readers had been guided into print by the legendary children’s publisher Velma V. Varner (“discoverer” of the young S. E. Hinton), who envisioned a great writing career for Norma, but who died too young of cancer in 1972. Other literary colleagues who championed her writing but died too soon include Donald Barthelme and John Gardner. I think these personal loses had the side effect of isolating Norma in terms of what we now call literary networks.

While her work did garner strong critical endorsement (both The Hidden Wide and Katzenjammered were reviewed favorably in the Review of Contemporary Fiction, a journal published by the Dalkey Archive), I think Norma may have oftener than not felt like a fish out of water. (See her hilarious story “No Democracy in Miracles or in Art” in Blatant Artifice, vol. 2 (1986)!) Her work seems set apart from any school, yet she was friends with almost every other writer and artist in Buffalo.

Which writer would Kassirer most like to have a drink with, and why?

For Norma: probably Lewis Carroll! Though Forster, Beckett, and Nabokov wouldn’t be far down on her list.

What’s the biggest mistake Kassirer felt she made as a writer?

Norma did speak regrettably about parting ways with an agent who liked her work…I don’t know all the details of what caused them to disassociate, but I knew she felt it didn’t help her publishing any. Also, she voiced concern that she had not spent enough time sending work out. This takes time away from the work of writing, but it can also lead to further possibilities.

On the other hand, Norma’s solitude gave her conviction: She corresponded for many years with the editor of a high-profile literary magazine, who continuously solicited and rejected her stories, telling her they were almost there. Finally—as told to me—she asked herself: Do I want to write stories, or do I want to write a certain type of magazine story? And she quit the correspondence with the editor. (Though she often thought to turn those letters into a story!)

Who was Norma reading?

Before she passed away, I recall Norma rereading her favorites—she said she was “testing” these works to see if they held up as she remembered, and she seemed to find that most did! The books she was rereading were—among others—those of Flann O’Brien, Harry Mathews, and Nicholson Baker.

Where did Norma Kassirer find her reading?

I imagine Norma found books everywhere, and especially through Talking Leaves Books here in Buffalo, including a complete run of the tiny and astonishing Hanuman series. I imagine her frequent visits to antique shops and garage sales also brought her the many editions of Alice in Wonderland and “Aliciana” she collected.

I want to use this question as a chance to talk about other influences upon her writing as well—both the poems and her fiction. Her brother David, a poet who died young, left her his burgeoning library of early New Directions books, which included the first pamphlet James Laughlin ever printed, Pianos of Sympathy by Montagu O’Reilly. This work had a strong effect on the course of Norma’s writing practice.

Also important to her were the books she inherited from her father’s library, including many adventure books for boys; “forbidden books” her mother kept in the attic, like Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood; and a cache of family papers, including the letters and diaries of a youthful ancestor who had been a minister and worried greatly over the worthiness of his soul…For Norma, the written wor(l)d was an intimate affair and a familial one, full of all the history and lore and secrecy that family stories entail.

Garden Etiquette

Say you’re in a garden

And you begin to notice that

There is one iris in the iris bed

Which resembles Edith Sitwell

Leave the garden immediately

Avoid the base temptation

To show off your cleverness

This is inappropriate in a garden

Whose point is a peaceful

Democratic presentation

Of beauty

However, have you noticed

That certain plants are now under copyright

And do not produce seeds?

I don’t know how this

Has anything to do with

Edith Sitwell

I do not think this would concern her

But you never know.

Which reminds me of something

That surprised me in a garden many years ago

Well actually in a sandbox in a garden

Where I was aimlessly pouring sand

From one container to another

And so was my friend Betty

Who suddenly informed me that

Her mother was a Davenport.

The quickness of my response

That my mother was a couch

Surprised me.

I got more useful information

From the encounter

Than I could use at the time.

What has this to do with Edith Sitwell?

I like her tone.

The ice is coated gray with winter

when Kathleen & I go down to the waterfront

on the first warm day after the long season

of unrelenting cold now ending in a burst of war,

the sun is everywhere. No blossoms yet, no leaves.

Just this splendid generosity of singing sun,

the river, and a full moon showing white

among the bare-branched trees.

River’s choked with a light-repelling blur

of thickened ice that’s slowly breaking up.

The tall bridge in the distance rises in a curve

and down again, beautifully conveying a busy traffic

reproduced in miniature reflection

in each small liberated space

through which the shining water shows.

The river’s pocked with moving pictures

in full color—a continuing stream

of upside-down bright trucks and glistening cars

advancing, as if by miracle,

along the upside-down curved bridge.

What lucky trick of light has scattered,

with such abandon, so much wonder?

A physicist would understand. I’ll ask Liz, I say.

We pause to watch some leaning trees

likewise vying for every opening mirror

in their trajectory, & succeeding.

Next evening Liz & I drive down to see,

but the ice has gone. It’s dark.

Water’s moving fast in a cold wind.

She doesn’t know why the reflections

leapt so gloriously all the previous afternoon.

We talk about the coming horror.

Falling through Hot Air to the Beach at Sunset

They call it the cathedral woods

& when I’m in there looking up

at sun flaming tall in tall pines

at day’s ebb how tempted I am

to piece together a church window

or two with green needles &

portions of the bleeding sky

although I know that teetering

on the edge of architecture like a

silent movie comic

has its perils

Thank god then that the nearby ocean

with a salt & ex-cathedrate air

is winkling me out to watch

it shatter on the shore in red

as the faceted sand stares like a fly

in all directions &

beach stones are washed & washed

again religiously

while layers of glandular fish

snatched by the gestural water

from its own deeps ride waves

to die on shore near glassy tide pools

that stare in crimson at a likewise sky

& so I land a trifle awkwardly

on a closely finned & shinning beach

that’s lain there lacquered by the sun all day

& amused to indolence by the power of

its multifarious points of view scans

with equanimity my arrival &’s

equally unmoved as

with a beach stone warming in

each hand I thrill

to a triumphant

shout of scarlet birds lifting

from the fragrant

pineal woods

Baby

The only way to begin is up the intricate mountain to its top. So say the rules of the dream. Down the chessboard complexities of the other side to deep waters—waves that leap like young foxes perfected in limb and tooth for a survival clearly not your own. A buoy flashes in neon a map to a pool calm as a hand mirror dropped glass side up. From a crack in its surface a brook emerges in the shape of a supple hand. Its fingers spread, tapping and trickling to a mild suburban island, built by instructions received by way of this extraordinarily detailed dream, in which the specifics of moving tons of topsoil and grass seed, full-grown trees, their roots burlap-wrapped, tulip and narcissus bulbs, lumber, bricks, etc. by clipper ship are carefully and clearly written in an old-fashioned script on sheets of fine rice paper.

On the island, children roll shrieking in extravagant delight down a greeny hill as a grey fox watches hungrily from a pen. The fox, however, is barely thought out. Its eyes, one presented in a complex swirl of clouded blue, the other new-leaf green, hint a possible carelessness of composition. Its tail, however, continues to evolve in a burst of vital energy so delighted with itself that it cannot stop.

The growling of the fox resembles the beginnings of human speech, at least to the large eager baby seated bunchily on the grass, alternately observing the creature and two sprightly young women, sunlit to a fare-thee-well, each of them grasping an end of a large, freshly laundered linen bed-sheet. They shake the linen, which the brilliant sun instantly reads as blue, blue as a length of silk in a Kabuki performance, held at either end by an actor, each of whom harbors the notion “river” and moves the silk, snaps and shakes it, as waves of tongue-in-cheek reality shiver from the cloth in the come and go of trembling Linden and Chestnut shade. Still, it is a sheet and ought to be hung and dried.

The baby has no words for these events. The baby shrieks, the baby sobs for such unfairness. Any passing fisherman might name them with ease, have concepts which would attach seamlessly to what is happening. The word metaphor comes rolling up a hill from a lobster net drying at the edge of the sea. The word engages the baby, who turns it over and over, bounces it, tosses it into the sky and screams with delight as it disappears.

“I am a tree!” announces a giddy flowering Linden. It delivers this message in scent. The shining baby breathes it in and shouts for the glory of the tree moving so exultantly through the shape of itself. The baby’s fingers burst in complicit blossom. No one notices. Not the young women, not a fisherman, nor the grey fox, now attempting a do-it-yourself assemblage. The baby watches its own finger-blossoms wither and fall off.

The grey fox breaks out of its pen and sits next to the baby, its elaborate and still evolving tail necessarily larger than the hastily-cobbled-together remainder of itself. The baby looks into the fox’s strange eyes. The fox stares hungrily back. The baby and the fox, as if embarrassed, look out to sea. The dreamer stirs and wakes. She turns to watch through her bedroom window the gyrations of a large linen sheet caught on a boxwood bush. Her eyes close while she stretches and yawns. She opens them as a breeze lifts the sheet and carries it out to sea. The sheet rises and falls, twirls in the style of a water spout, fiddles with resembling a sail and sinks. The baby and the fox dwindle like sand castles in a persistent scribbled wash of Palmer Method waves as the dreamer follows the wrinkled stairway down to breakfast.

All poems from Minnows Small as Sixteenth Notes: The Collected Poems of Norma Kassirer. Edited by Ann Goldsmith and Edric Mesmer. Buffalo: BlazeVOX [books], 2015. Copyright © 2015 Susan Kassirer.